Parte I: Bitcoin como árbol, persistencia y estructuras profundas

Un ensueño

Quizás si Había sido más descarado, el título de la primera parte de esta serie habría terminado como algo más tentador, algo contundente como”Bitcoin es una palmera y Fiat es un coco”. Pero para bien o para mal, ese título se sentía saturado de demasiada ligereza, demasiado tropical y trivial para un tema tan importante.

Sin embargo, la verdad es que las imágenes de las palmeras habrían sido muy precisas alegoría de cómo evolucionará la hoja de ruta de bitcoin y fiat a medida que avancemos en el siglo XXI. Una palmera real, roystonea oleracea, que se balancea febrilmente en una ráfaga torrencial, aunque nunca deja de retener un agarre firme a sus raíces en las profundidades del suelo. Y como con cualquier tormenta, la única necesidad darwiniana de este árbol es la supervivencia, para capear la tempestad lo más ileso posible.

Otros árboles y estructuras pueden romperse y estallar en capitulación ante los duros caprichos de la naturaleza, dejando más luz solar para que nuestra palma real la absorba una vez que el cielo se haya despejado. Los escombros de todo lo que no habían sido lo suficientemente robustos para sobrevivir al ataque, metabolizados por colonias de termitas y fuegos de matorrales, se transformaron en un suelo fértil y exuberante. Una nueva capa base a partir de la cual reconstruir y prosperar. Una metáfora adecuada, a la luz del hecho de que el suelo es el único medio físico jamás observado en la naturaleza capaz de transformar la muerte en vida. Del mismo modo, un dinero sólido absolutamente escaso e incorruptible es el único medio económico capaz de dar vida económica a un sistema financiero decadente y degradado.

Una advertencia

“Pasar inofensivamente su tiempo en la pradera

Solo vagamente consciente de una cierta inquietud en el aire

Es mejor que tengas cuidado

Puede que haya perros

He mirado a Jordan y he visto

Las cosas no son lo que parecen

¿Qué obtienes por fingir que el peligro no es real

Manso y obediente, sigues al líder

Por pasillos trillados hacia el valle de acero

¡Qué sorpresa!

Una mirada de choque terminal en tu ojos

Ahora las cosas son realmente lo que parecen

No, esto no es un mal sueño”

-Roger Waters,”Sheep”, 1977

Fuente: Nareeta Martin, @LudiMagistR

Una profecía

“¿Escuchaste acerca de la rosa que creció de una grieta en el concreto?

Al demostrar que las leyes de la naturaleza estaban equivocadas, aprendió a caminar sin tener pies.

Es curioso, parece que al mantener sus sueños, aprendió a respirar aire fresco.

Larga vida a la rosa que creció del concreto cuando a nadie más le importaba ”.

–Tupac Shakur,“ La rosa que creció del hormigón , ”1999

Antes de que podamos apreciar completamente la característica de persistencia de bitcoin inferenciada anteriormente, tal vez sea útil contextualizar cómo y por qué tal”antifragilidad”(algo que definiremos con mayor detalle más adelante) inevitablemente se revelará como un trueno, una bofetada en el rostro, lo que nos permite a todos ser testigos de su utilidad profundamente infravalorada.

Para lograr esto, tomemos un pequeño desvío usando una versión modificada de la técnica de cuestionamiento socrático.

Una teoría: La estampida de la clase de inversionistas en masa

El estimado inversor tecnológico erudito Balaji Srinivasan, en su modelo conceptual de una economía seudónima descentralizada, ha declarado de manera controvertida:

“En el siglo XIX, todos eran agricultores. En la década de 1900, todo el mundo se dedicaba a la fabricación. En la década de 2000, todo el mundo se convierte en inversor… Y una de las cosas que la gente no comprende hasta que se convierte en inversor es la idea de que el dinero es abundante”.

-Balaji Srinivasan,” Invierta como el mejor podcast con Patrick O’Shaughnessy ”

Fuente: Balaji Srinivasan

A Discusión

Tomemos la declaración anterior al pie de la letra y aceptémosla por el momento como una realidad a priori en evolución. Creo que la mayoría de nosotros estaría de acuerdo en que tal ampliación del alcance de la clase inversora está experimentando un impulso cada vez más rápido, particularmente en el mundo pospandémico. Es difícil negar la evidencia sólida (discutida a continuación), así como el foco cultural observado que ha enfatizado la inversión autodirigida en el mercado de valores. La evidencia está en todas partes, incluso desplazándome por mi suministro de noticias mientras escribía este ensayo:

“Robinhood trabajando en una función para permitir que los usuarios inviertan en cambio de repuesto”

“La inversión de cambio de repuesto ha se ha convertido en una estrategia cada vez más popular para los nuevos operadores bursátiles y es una pieza clave de aplicaciones de la competencia como Acorns, Chime y Wealthsimple ”.

Con la oferta pública inicial simbólica de Robinhood ahora grabada en nuestra memoria reciente, los titulares como se indicó anteriormente son ejemplos perfectos para nuestra discusión. La inversión en el mercado de valores micro-financiada personificaría esta evolución hacia una clase de inversionistas masivos. Yo, por mi parte, veo este cambio a mi alrededor, en mi vida profesional en la industria de los fondos de cobertura, en una cultura de creciente FOMO, codicia y ansiedad, hasta mis interacciones personales con amigos y familiares y en las redes sociales. Incluso creo que esto es lo que muchos políticos y tecnócratas están aspirando conscientemente a incentivar. Y me molesta.

¿Cuáles son las implicaciones de tal transformación social? ¿Y cuáles son sus causas fundamentales?

Estas preguntas abiertas que surgen de esta observación son una de las razones por las que estoy tan atraído e intrigado por la conjetura de Srinivasan en primer lugar. Su declaración abre la puerta a una variedad de discusiones y toca algunos temas muy importantes.

Algunos de estos temas relacionados con la inevitabilidad de una economía descentralizada son temas que se discutirán con mayor detalle en la segunda parte de esta serie. Mientras tanto, establezcamos el escenario entendiendo por qué se está fomentando una clase de inversionistas masivos, cómo conducirá a una centralización aún mayor y cómo todas estas puertas abiertas son escaleras mecánicas unidireccionales, garantizadas para conducir a más árboles de decisiones dependientes del camino. , y eventualmente generar una inestabilidad casi infinita y una fragilidad sistémica.

Y lo que quedará abrumadoramente claro será la interacción holística entre la inevitabilidad y la insostenibilidad de este camino en un lado de la moneda. Y luego la persistencia de bitcoin en el otro lado, esperando pacientemente su turno para ser izado en el aire, girando frenéticamente, aunque tranquilo y sereno mientras anticipa pacientemente un aterrizaje boca arriba.

Una metáfora sándwich

Lo que la profecía de Srinivasan expone sin saberlo es la realidad de un peligroso período de transición en el que se encuentra actualmente la economía global. Estamos situados en un confuso estado de limbo en este momento, intercalados precariamente entre la descentralización y la centralización.

La energía cultural de este estado temporal fluido ciertamente solicita un cierto”malestar en el aire”, aunque el creciente descontento es palpable. Y así como los eventos de la pandemia de COVID-19 han impulsado la intensificación de muchas tendencias, una de estas tendencias es de hecho una manifestación de un”proletariado”y una clase inversora en expansión agresiva. Y aunque tal progresión tiene muchos atributos positivos, que van desde el autoempoderamiento, la oportunidad para la creación de nueva riqueza a corto plazo y la educación financiera sobre los mercados, la gestión de riesgos, el dinero y la teoría económica, todos estos beneficios son lamentablemente equivocados y a corto plazo. de vista normal. Al final, estos beneficios tan tangibles están destinados a ser diluidos y derrotados por fuerzas ominosas.

Las principales razones de por qué una mercantilización de la clase inversora es una evolución tan peligrosa se pueden atribuir principalmente al tiempo, contexto histórico y las implicaciones de lo que esta sociedad de inversionistas masivos requerirá en forma de efectos derivados segundos y terceros.

Tenga paciencia a continuación, ya que esta primera sección es inevitablemente pesada con algunos datos y terminología financieros. Sin embargo, estos datos son imprescindibles para ayudarnos a comprender la imagen más amplia de lo que está sucediendo y pagarán dividendos en el artículo y la serie a medida que ampliemos las ideas más importantes de nuestra tesis.

No soy un agorero. No vivo en un búnker. He visto a demasiados inversores ser víctimas de narrativas demasiado bajistas, perdiéndose grandes inflaciones de activos que esa negatividad ofusca. Sin embargo, el propósito de este ensayo no es presentar una tesis de inversión a corto plazo. Dicho esto, lo que he comenzado a presenciar con creciente claridad como inversionista, como miembro de nuestra sociedad que se preocupa por el mundo que heredan mis hijos, es una evidencia creciente de una trampa inevitable. Una trampa con una única solución realista. Por lo tanto, los datos financieros aquí incluidos son simplemente una herramienta, un lenguaje que nos ayuda a ver esta información. De hecho, el mensaje principal de esta serie es mucho menos sobre finanzas y mercados, y mucho más sobre la naturaleza humana, la historia y el impacto que los incentivos y el conflicto ideológico tendrán en el resultado de la mayor parte de este siglo.

Entonces, tengan paciencia mientras nos llevo más abajo en esta madriguera de bloques predestinados en nuestra cadena de reacciones.

Bloque uno: El contexto histórico importa. Resulta que el tiempo lo es todo

Irónicamente, se está formando una clase de inversionistas masivos, impulsada por premisas falsas e incentivos perversos, después de un período histórico sin precedentes de inflación de activos.

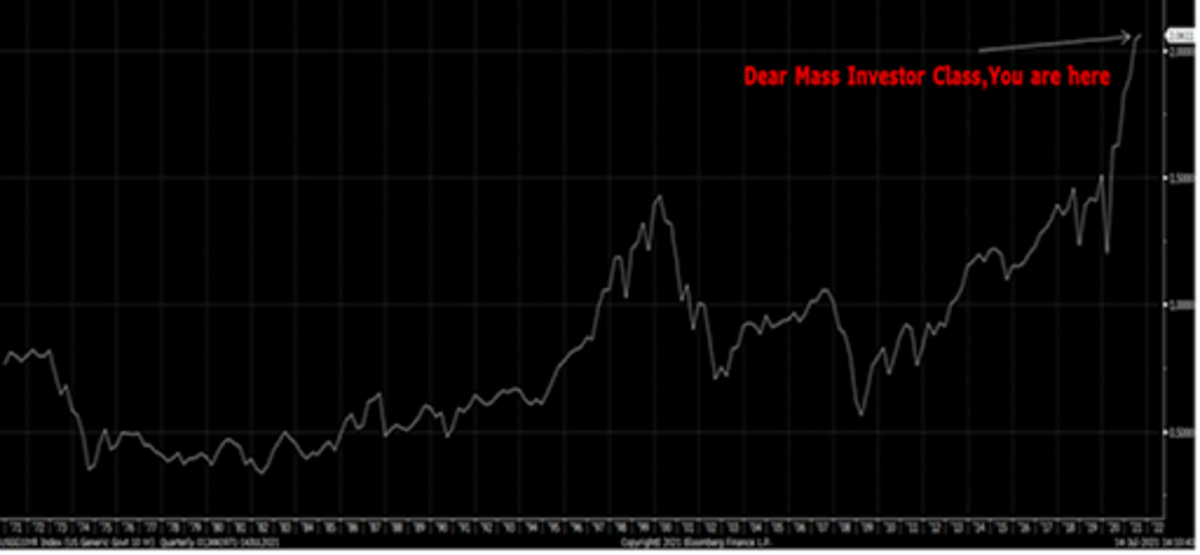

Acabamos de presenciar más de 40 años sin precedentes de inflación de activos financieros, acumulación de deuda, desregulación y opulencia monetaria. Un mercado alcista de bonos épico donde la tasa libre de riesgo ha pasado del 16% a casi cero, el mercado de valores en relación con nuestra capacidad productiva está en un récord (ver el gráfico a continuación), casi todas las métricas de valoración están en máximos históricos y el comportamiento irracional ha se expandió dramáticamente (ejemplificado por SPACs, r/WallStreetBets, acciones de memes, deuda de margen minorista y, por supuesto, muchos bolsillos del universo”cripto”).

Al mismo tiempo, el apalancamiento gubernamental y empresarial también se encuentra en extremos. Estas estadísticas se vuelven aún más excesivas una vez que se tienen en cuenta los pasivos gubernamentales fuera del balance, como la seguridad social, el seguro médico, las obligaciones de pensiones y los presupuestos de defensa fuera del balance. Esto se suma a tener en cuenta los optimistas supuestos de orientación corporativa y muchos equipos de administración de la empresa se vuelven desesperadamente creativos con trucos para agregar ganancias y estrategias agresivas de ingeniería contable. Dicho de otra manera, el inversor individual se está profesionalizando al final de una de las fiestas más grandes y homéricas de todos los tiempos. Perdone la metáfora cliché del béisbol, pero esto es como si un jugador fuera llamado de las ligas menores justo antes de la temporada baja, después de una final dramática de siete juegos en la Serie Mundial.

¿Es esto realmente un buen desarrollo para la sociedad? En realidad, esto es bastante típico del comportamiento observado y la participación que se produce en los períodos pico de los mercados alcistas. Sin embargo, aquí hay algunas diferencias clave en relación con el estallido de burbujas típico.

En primer lugar, nos referimos a ese comportamiento en el contexto de estas inversiones que se realizan bajo la apariencia de una profesionalidad recién descubierta y cambios profesionales empoderados. Existe una sensación de derecho a la riqueza y la expectativa tanto de los responsables políticos como de los nuevos inversores de que tienen derecho a obtener riqueza de los mercados de capital, y hacerlo con muy pocos riesgos implícitos. Además, como lo demuestra la disminución de la tasa de participación laboral, una sociedad de inversores crea un doble riesgo. A medida que más personas renuncian a otras formas de trabajo, nos convertimos en una sociedad de”arrendatarios”en lugar de”hacedores”. Revertimos la flecha de la historia que siempre ha conducido a una mayor especialización y división del trabajo. Por lo tanto, no solo hay más personas ahora expuestas a activos financieros que nunca, sino que esta cohorte en expansión lo ha hecho a costa de la pérdida de empleo y los salarios ganados en otros lugares.

Lo que está en juego es mayor y el margen de error menor. Y tal comportamiento en realidad está siendo respaldado tanto culturalmente, como un medio de rebelarse contra la clase rica, como políticamente, como un derecho liberal a la propiedad de activos para ver una mayor distribución, sin tener en cuenta el valor subyacente y el riesgo de dichos activos. Esto es diferente a una simple burbuja financiera transitoria. Este es un globo de aire caliente flotando a través de la estratosfera, para nunca volver a sentir el firme abrazo de la tierra.

EE. UU. Capitalización bursátil en relación con el PIB en dólares nominales, 1971 al presente. Fuente: @LudiMagistR, Bloomberg

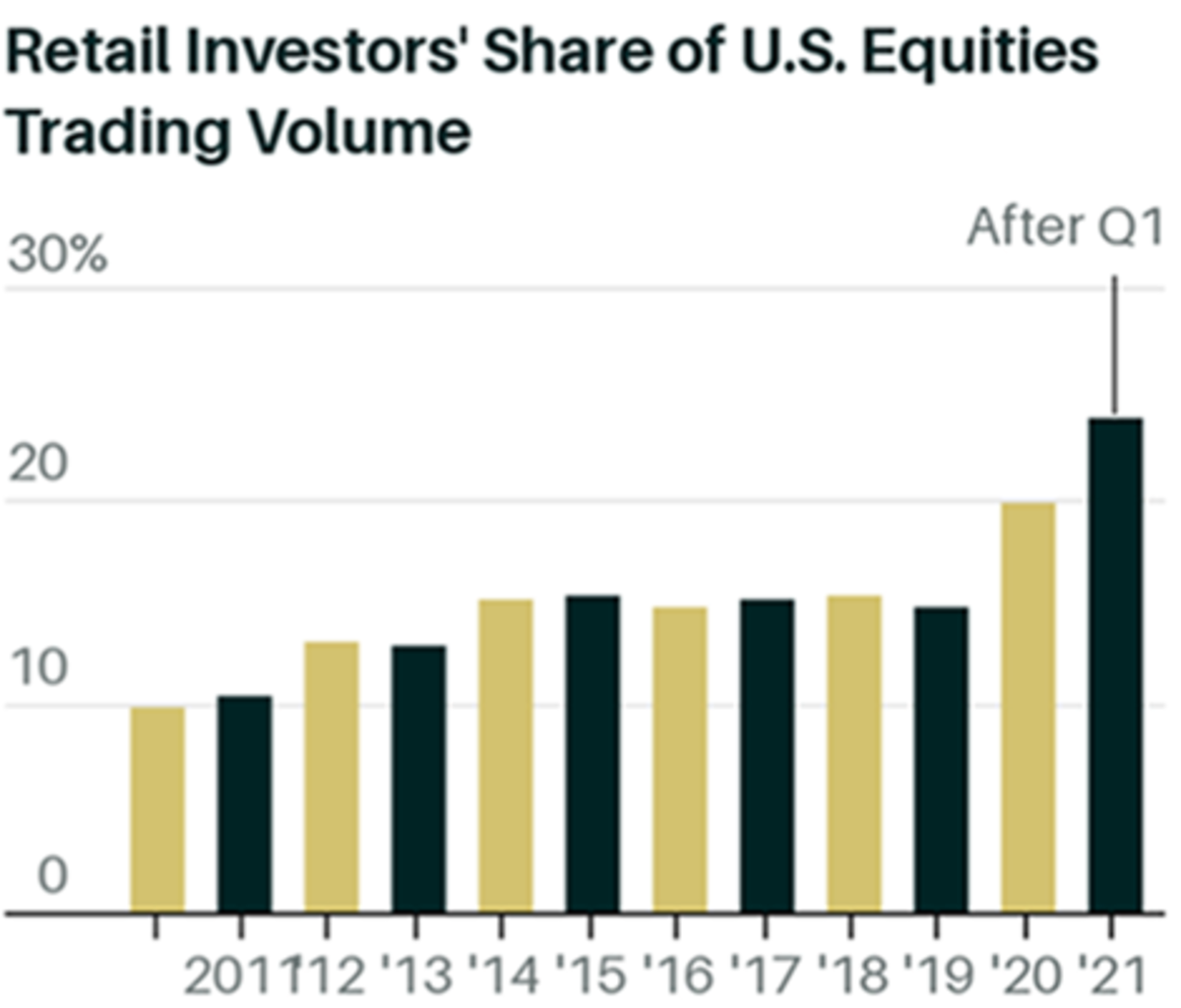

La adopción masiva de la clase de inversionistas se está acelerando.

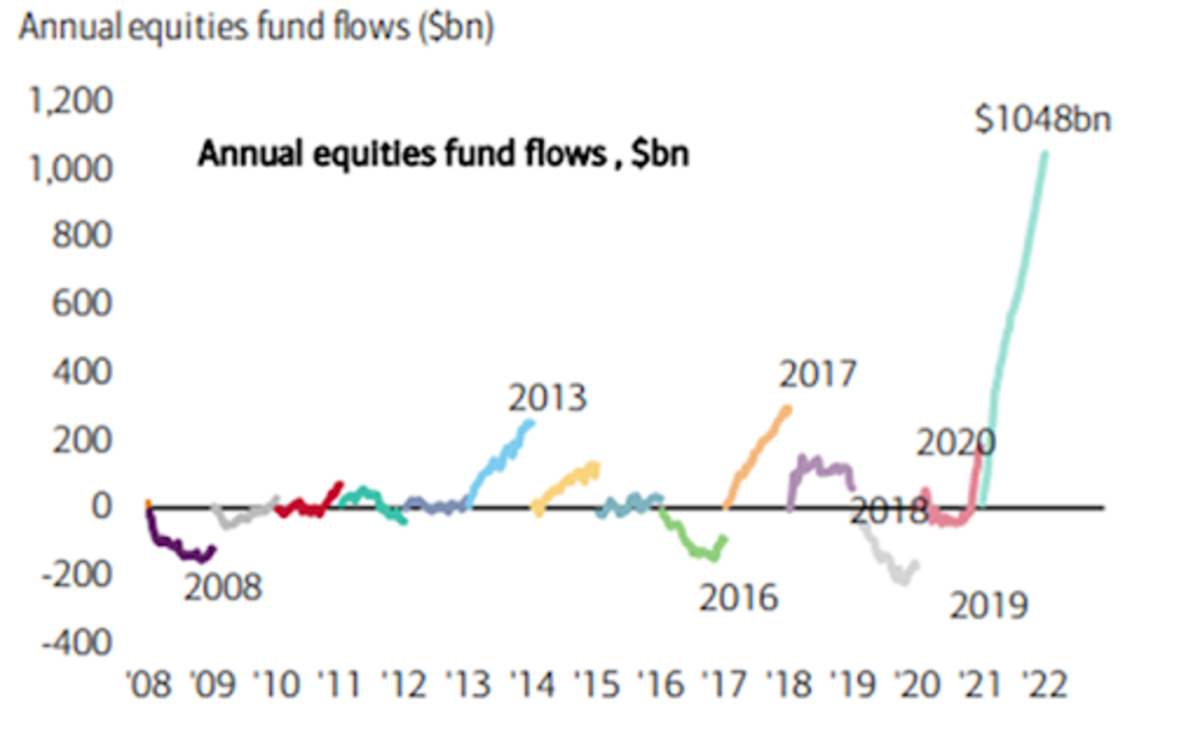

La tasa anualizada de entradas de capital hasta ahora para 2021 es de aproximadamente $ 1 billón. ¡Para cierta perspectiva, esto es mayor que la entrada total acumulada en acciones durante la totalidad de los últimos 20 años!

Fuente: Bank of America; Michael Hartnett

El gráfico anterior ilustra la entrada anualizada de $ 1 billón en acciones en 2021, en comparación con las entradas de acciones acumuladas de $ 800 mil millones de 2001 a 2020. Dejemos que eso se hunda por un minuto antes de continuar con este ensayo. Vemos tantos gráficos, memes y estadísticas locos y sin precedentes en estos días, que es fácil pasar por alto este gráfico. Pero esto realmente dice algo profundamente preocupante sobre hacia dónde se dirigen las cosas.

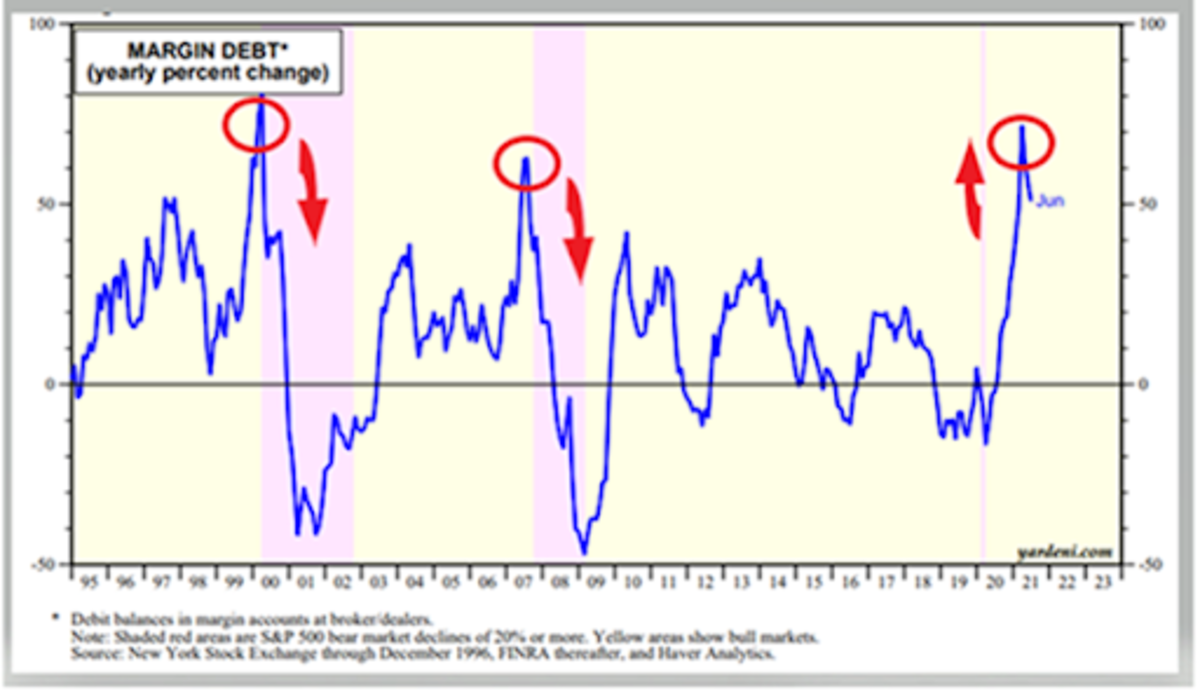

La deuda de margen para el comercio de acciones apalancadas, rastreada por la Autoridad Reguladora de la Industria Financiera (FINRA), ha sido históricamente un indicador del entusiasmo y la codicia de los inversores individuales (o”minoristas”) dentro de los mercados de valores.

El siguiente gráfico muestra la tasa porcentual anual de aumento en la deuda de margen, que históricamente ha anticipado recesiones, marcadas por las regiones sombreadas en violeta. Sin embargo, podemos ver que en el período reciente, el margen se ha disparado a un ritmo históricamente sin precedentes, quizás alcanzando su punto máximo en el corto plazo.

Pero la observación clave aquí es que este rápido aumento se ha producido después de esa barra púrpura, en lugar de antes. La deuda de margen no precedió a una crisis, sino que fue la respuesta a ella. Vimos indicios de esto en 2009, pero eso fue después de una purga masiva del apalancamiento bancario y de la vivienda, y una gran depreciación del valor de los activos. La crisis de COVID-19 no permitió tal purga e instituyó políticas para revitalizar drásticamente la inversión de capital minorista. Este es un comportamiento nuevo.

Fuente: Ed Yardeni (yardeni.com); BOLSA DE NUEVA YORK; FINRA; @LudiMagistR

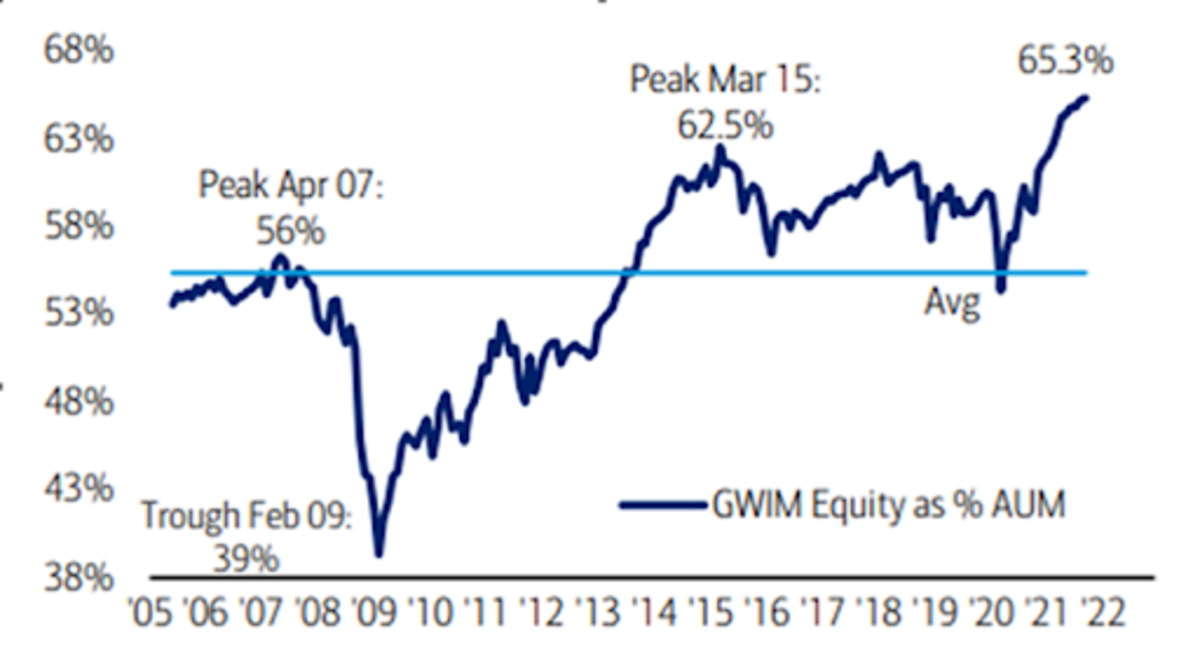

La asignación de capital de los clientes de Bank of America (BofA) Wealth Management está en máximos históricos.

BofA participaciones de capital de un cliente privado como porcentaje de los activos bajo administración. Fuente: Bank of America; Michael Hartnett

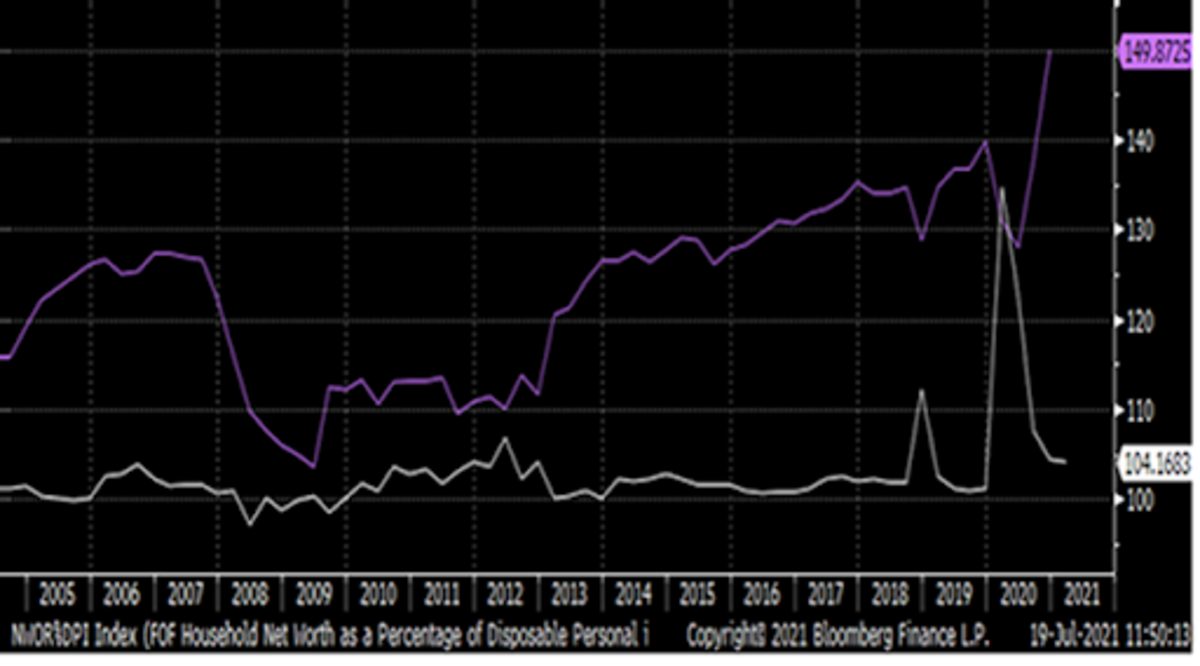

Valor neto del hogar como porcentaje del ingreso personal disponible (violeta), frente a la relación entre la tasa de crecimiento interanual del ahorro personal/la tasa de crecimiento interanual del patrimonio neto (línea blanca. Fuente: @LudiMagistR, Bloomberg, Reserva Federal de St. Louis

Lo que demuestra este último gráfico directamente arriba es que las personas en los EE. UU. Ya no están generando ahorros a partir del exceso de ingresos, sino de la inflación de activos. Definitivamente arriesgado y los activos financieros sensibles a la inflación son ahora las principales reservas de valor para la mayoría de los hogares que pueden permitirse poseerlos.

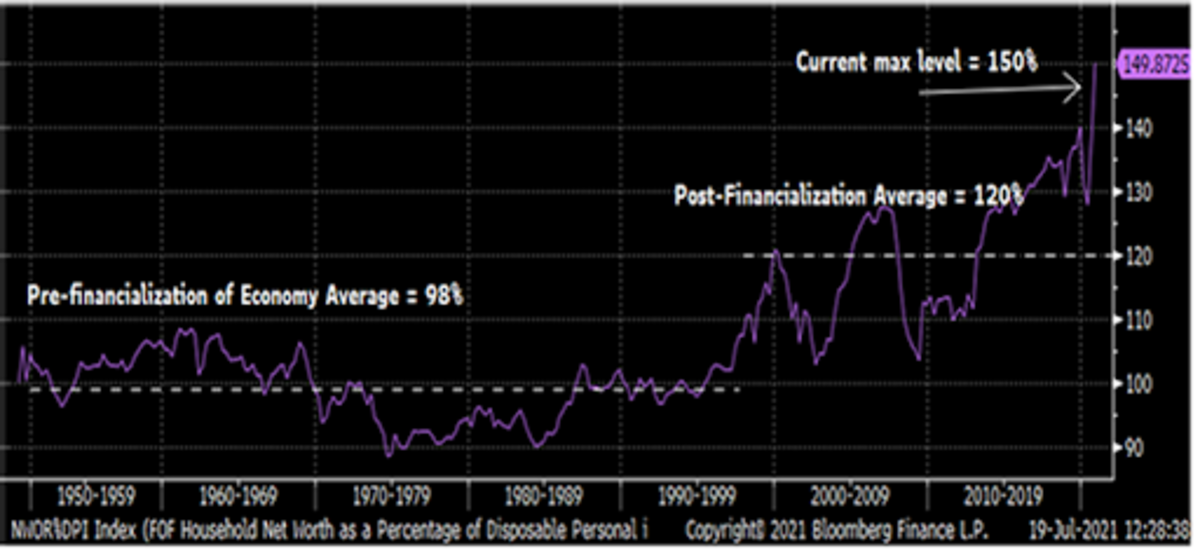

Para un contexto histórico más amplio, a continuación se muestra el mismo patrimonio neto del hogar como porcentaje de ingresos personales disponibles, que se remontan a 1945.

Fuente: @LudiMagistR, Bloomberg, Reserva Federal de St. Louis

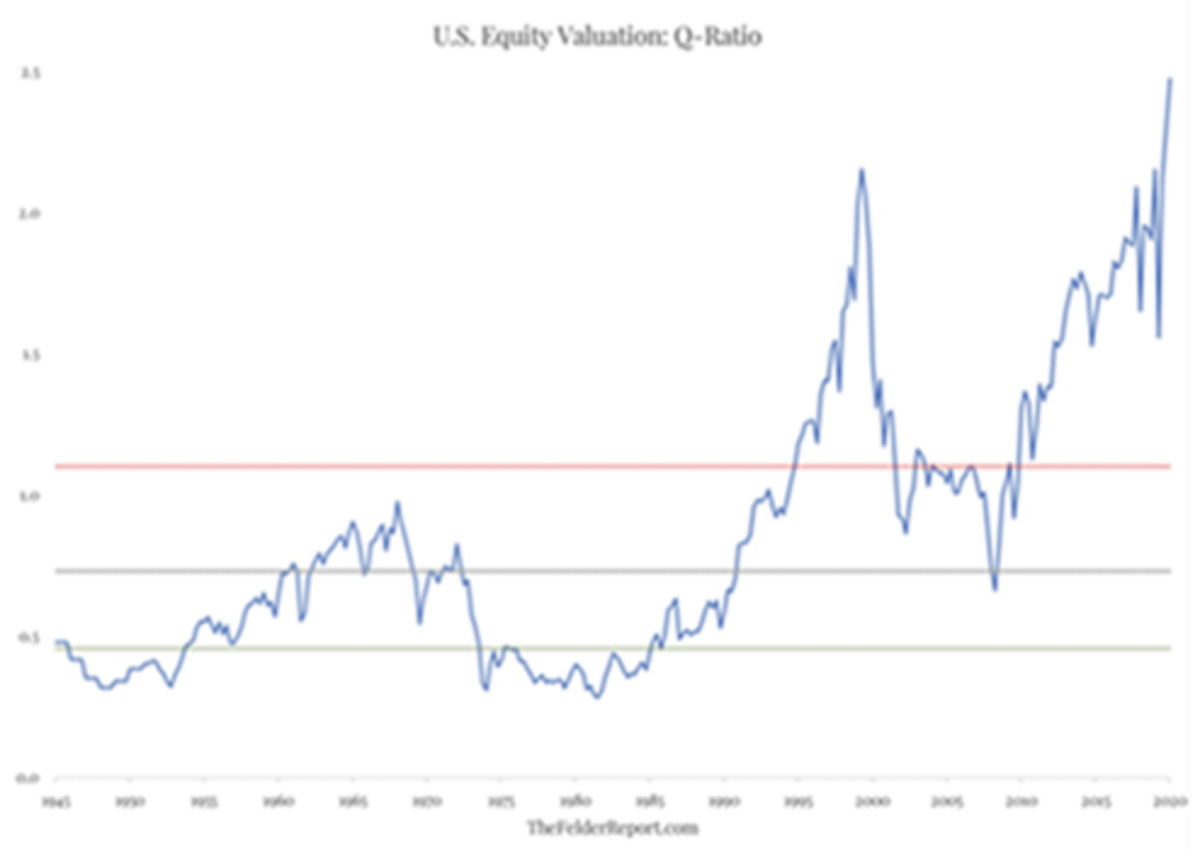

La muerte si la destrucción creativa

A continuación se muestra un gráfico de un indicador conocido como Cociente de Tobin, también conocido como”Relación Q”. En esencia, es la razón de la capitalización actual del mercado de valores, dividida por el costo de reemplazo del mundo real de los activos asociados con ese capital.

Como se visualiza en el gráfico a continuación, esta proporción se encuentra en niveles históricamente sin precedentes. El gráfico abarca desde la época posterior a la Segunda Guerra Mundial hasta el presente y expresa que las valoraciones de las acciones son actualmente casi dos veces y media su valor de reposición. Esto se compara con una proporción promedio de 75 años más cercana al valor de reemplazo.

Es cierto que este análisis no está exento de matices, ya que nuestra economía ha pasado a una era de la información caracterizada más por economías digitales, en la que los activos se vuelven más intangibles y, por tanto, se hace más difícil valorar los costes de reposición como la propiedad intelectual. y la buena voluntad de los efectos de red. Pero incluso si tomamos en cuenta este cambio, la relación Q actual sigue siendo más de tres veces el valor de reemplazo, en comparación con la era de la quiebra anterior a las puntocom de la década de 1990 de un promedio de valor de reemplazo de 1.4 veces, y un valor de reemplazo posterior a dot.com. Promedio de la era del busto de más cerca de 2,3 veces el valor de reemplazo.

No importa cómo se dividan los datos, lo que esto demuestra es la magnitud de las empresas valoradas financieramente de una manera completamente dislocada de su realidad económica. Las llamadas empresas “zombis” que no deberían existir en un mercado verdaderamente libre, que a menudo tienen grandes cantidades de deuda improductiva para mantenerse, prosperan en un mundo tan feliz. Estas entidades atrapan el buen dinero y lo mantienen petrificado dentro de estructuras en descomposición. Como inversionista profesional que pasa mucho tiempo invirtiendo en crédito corporativo de alto rendimiento, veo esta locura a diario.

En algún momento, la única forma de reconciliar estos desequilibrios es mediante reestructuraciones masivas, quiebras e impagos de la deuda, o mediante la inflación. La inflación actúa para aumentar el denominador del valor de reposición, en una poción de alquimista de rectitud superficial. La inflación, como se ha visto a lo largo de la historia de la humanidad, es, con mucho, la solución más aceptable para los economistas, los inversores de Wall Street y, por supuesto, los políticos que tienen una visión del mundo de dos a cuatro años.

Pero la ironía de este hecho es que tal comprensión también explica cómo llegamos aquí en primer lugar.

Cociente de Tobin, desde 1945 hasta el presente: valoración bursátil relativa al valor de reposición de la economía. Fuente: Informe Felder

La negación de la calidad

A continuación, podemos observar más evidencias de deterioro de la calidad. En este caso, no nos referimos solo al colapso de la destrucción creativa y la calidad del balance, sino a la calidad de las ganancias corporativas en general.

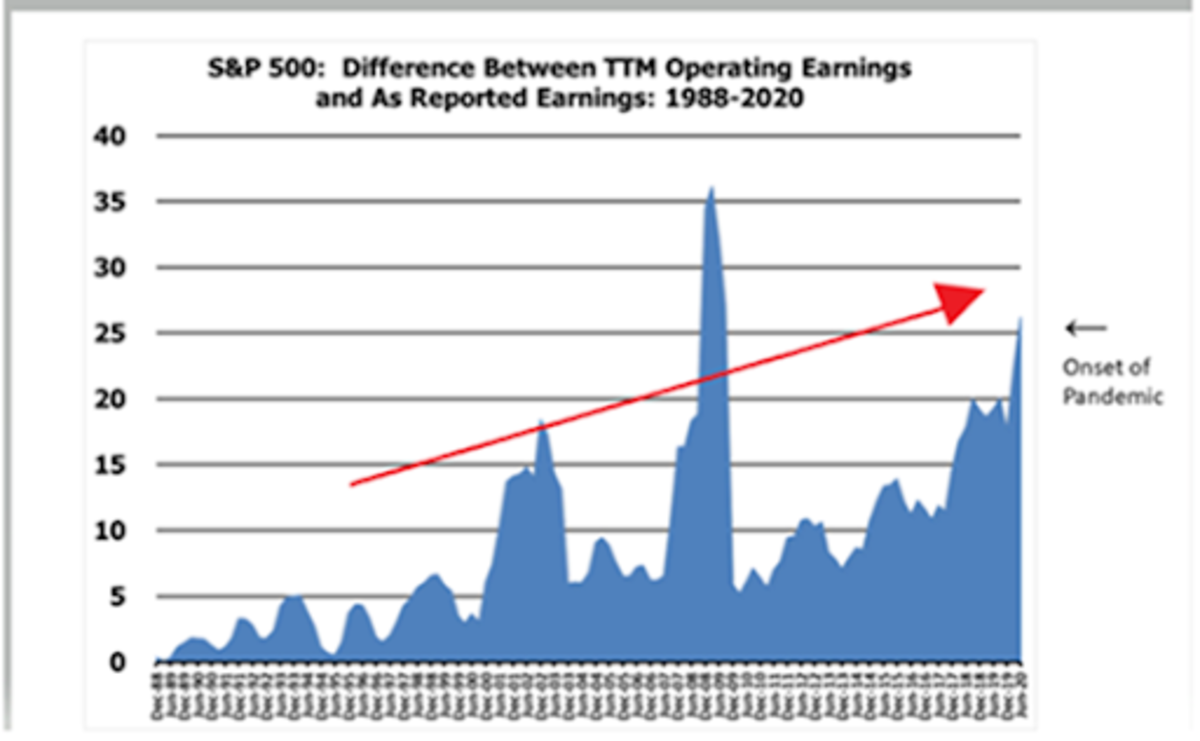

Las mismas métricas en las que confiamos para ayudarnos a determinar el complejo mundo de datos que nos rodea han sido manipuladas y manipuladas hasta el punto en que la medida se ha convertido en el objetivo. GAAP, o”principios de contabilidad generalmente aceptados”, es un protocolo de contabilidad diseñado para limitar la degradación de las ganancias a través de adiciones opacas, arbitrarias y engañosas. A veces, de hecho, hay ajustes válidos que no son PCGA que deben realizarse para obtener una imagen precisa del verdadero potencial de ganancias de la tasa de ejecución de una empresa. Sin embargo, en general, tales ajustes “no GAAP” a los informes GAAP han tendido a producir una imagen de menor integridad y confianza.

A pesar de esto, nos hemos acostumbrado tanto a tales ajustes que los participantes del mercado y los reguladores han aceptado la desviación gradual sin pestañear. Quizás no sea sorprendente que los ajustes que no son PCGA se convirtieran por primera vez en “ arraigados en la estructura de los informes financieros ”en 1988, cuando se aceleraron muchas políticas de financiarización de la economía. También vale la pena mencionar que la mayoría de los gastos de compensación basados en acciones se vuelven a agregar a las ganancias que no son PCGA. Por lo tanto, hay una dinámica autorreferencial en juego aquí, ya que las ganancias no GAAP aumentan la apariencia de las ganancias, lo que ayuda a inflar las valoraciones de las acciones, lo que a su vez infla la compensación basada en acciones que está ayudando a inflar las ganancias en primer lugar. !

El siguiente gráfico muestra el margen de las ganancias no GAAP menos las ganancias GAAP:

Este margen tiende a aumentar en las recesiones a medida que se acumulan las pérdidas no operativas.. Pero curiosamente, en los años posteriores a la recesión, la tendencia reanuda su camino hacia una calidad más débil.

Fuente: Lark Research

Bloque dos: Un globo aerostático

El resultado de esta situación es que la fragilidad del sistema aumenta rápidamente, lo que requiere una dependencia de la ruta determinista del aumento de datos manipulación, apoyo gubernamental, regulación e intervención de mercado libre.

Un contexto histórico de valoración y desempeño de activos como el articulado anteriormente significa que ampliar la exposición de activos financieros a una población más diversa y más grande crea un riesgo sistémico inaceptable para la economía en el largo plazo. Para tomar prestada una frase de la teoría de juegos, el mercado de valores se convierte en un único punto de falla.

Como expuse en un artículo anterior,”Pensar demasiado pequeño y las trampas de la narrativa de la inflación”, también se convierte en un medio de impresión de dinero insidiosa a través de la creación de activos financieros, en lugar de evidente expansión de la oferta monetaria de las generaciones de nuestros padres y abuelos. Este incentivo para inflar por decreto de riesgo moral, o inflación de activos financieros garantizada implícitamente, es aún más fácil de lograr cuando la tecnología hace que cada vez más productos y servicios sean más baratos o totalmente gratuitos, y cuando las restricciones de oferta como las que estamos experimentando ahora hacen que el consumo de”cosas”físicas menos deseables o incluso imposibles en algunos casos.

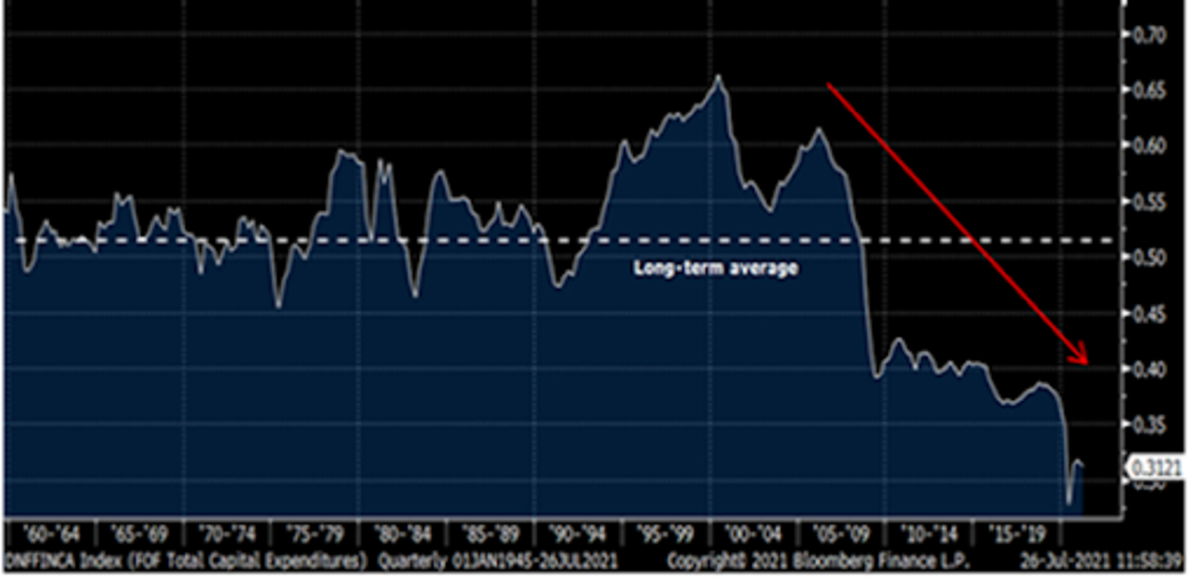

Los mercados de deuda con precios adecuados crean obstáculos para el retorno de la inversión que incentivan solo aquellos esfuerzos que pueden crear nuevo capital productivo. La deuda demasiado barata incentiva el apalancamiento del capital social existente, sin necesidad ni deseo de obtener ganancias productivas. E incluso cuando finalmente se realizan nuevas inversiones de capital, el incentivo claro es hacerlo con ese financiamiento barato, en lugar de ahorros y flujo de caja. Esto eventualmente lleva incluso a los asignadores de capital productivo por caminos de apalancamiento excesivo.

Mientras tanto, a medida que los activos se inflan, la única forma de mantener el nivel de vida deseado implica transferir los ahorros a activos financieros más riesgosos como acciones, bonos y bienes raíces. Esto se debe a que el rendimiento de la inversión para la formación de nuevo capital siempre tarda más en desarrollarse en relación con la recuperación del capital social existente cuando la inflación está prácticamente asegurada por el riesgo moral sistémico. Agregue a esto el hecho de que las tasas de interés oprimidas y manipuladas están robando del futuro mismo para el cual se invertiría nuevo capital (discutido más abajo). Esto desincentiva aún más cualquier inversión material en nuevo capital social.

El siguiente gráfico muestra una relación de los gastos de capital totales de EE. UU. en dólares nominales, divididos por el denominador del dinero base puesto en el sistema, medido por la oferta monetaria M2. Desde que alcanzó su punto máximo en la crisis de las puntocom, la inversión en nueva formación de capital se ha desplomado en relación con la creación de nuevo dinero. Esto plantea la pregunta retórica de dónde está fluyendo todo el exceso de dinero nuevo, si no hacia la formación de nuevo capital. La respuesta son los activos financieros, por supuesto.

Fuente: Bloomberg; @LudiMagistR

De esta forma, los incentivos son tan claros como una dura babosa de Stoli. Y, durante la mayor parte de los últimos 30 años, solo los ricos han sido parte del diseño de este juego, obteniendo un asiento en la mesa con sus activos existentes, su “ prueba de participación “.

Sin embargo, es cada vez más evidente que el riesgo moral omnipresente, la reducción de las preferencias temporales y los ahorros recién acuñados son los factores más importantes. siguiente etapa eficiente en este árbol de decisiones de falso libre albedrío. Los formuladores de políticas de ambos lados del pasillo tienen incentivos para adoptar tal narrativa. Apuntarán a impulsar el patrimonio neto de la clase media en contraposición al viejo libro de jugadas relacionado con la mejora de los ingresos de la clase media, la educación, las redes de seguridad social y la redistribución de impuestos. Mientras tanto, el lado derecho pasará gustoso su batuta de la economía monetarista del lado de la oferta, con su autoengaño”hopium”de que la corporatocracia estadounidense compartirá la riqueza y de la misma manera abrazará la inflación financiera y el capitalismo socializado. La derecha percibirá tal centralización de los mercados de capitales como desagradable, pero mejor que una alternativa de socialismo y redistribución keynesianos. Ambas partes cambiarán sus principios básicos por una solución que realmente ofrezca resultados, aunque a un costo tremendo.

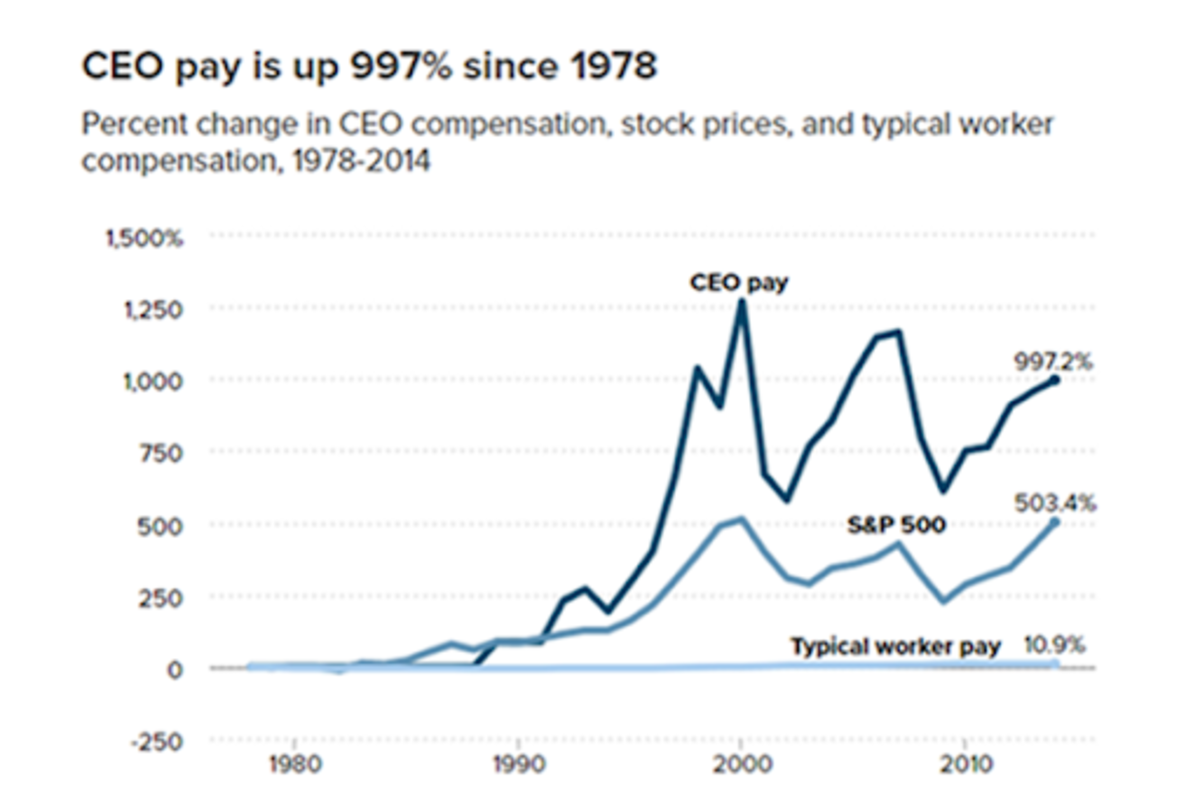

Si usted fuera un responsable de la formulación de políticas y observara el siguiente gráfico, ¿cuál sería el mecanismo menos arriesgado y más obvio para rectificar una divergencia tan inmensa? Fácil: simplemente vincule el “salario típico del trabajador” al S&P 500, ¡y boom! ¡Misión cumplida!

Fuente: Instituto de Política Económica; Datos económicos de la Reserva Federal (FRED)

De acuerdo. Entonces, supongamos que ahora tenemos la pelota en marcha y, de hecho, estamos comenzando a vincular la compensación laboral al mercado de valores a través de varios medios. Pero, ¿cómo se logra tal hazaña? No es como si el gobierno pudiera obligar a los empleadores a pagar salarios en forma de índices bursátiles.

Bueno, no directamente. La respuesta está en una receta combinada de incentivos alterados. El riesgo moral y el respaldo implícito de los precios de las acciones como se describió anteriormente es sin duda el epicentro de tal estrategia.

Pero hay un sinfín de otras: mayores ahorros individuales inducidos fiscalmente con incentivos para invertir cualquier exceso de ahorro; Esfuerzos de desglobalización que alientan a los ciudadanos estadounidenses a invertir y ahorrar más a nivel nacional que a las importaciones de los consumidores de China; y la progresión natural de la tecnología y la innovación financiera simplemente”haciendo lo suyo”, creando mayores rampas de acceso para la inversión democratizada; ejemplos de esto serían productos como los fondos cotizados en bolsa (ETF), plataformas comerciales como Robin Hood que simplifican al usuario experiencia, blogs basados en redes sociales, canales de YouTube y plataformas alternativas de información y entretenimiento que generan confianza y luego rocían este caldo con una fuerte dosis de FOMO a nivel cultural. Otro mecanismo obvio sería a través de impuestos sobre la renta más altos para desviar dinero hacia la inversión financiera, y mayores impuestos sobre las ganancias de capital para incentivar el comportamiento de HODL en el mercado de valores. Estos son solo ejemplos. El punto aquí es que hay una caja de herramientas ilimitada disponible para promover tales objetivos, tanto de manera intencional como orgánica a través de los incentivos naturales del sistema.

“Pero espera”, dices. “¿Qué hay de malo en una mayor tasa de ahorro y menos consumo? Después de todo, ¿no es este un principio fundamental de muchos Bitcoiners? ”

El problema es que incluso antes de un cambio de carrera social como el que estamos presenciando hoy, el nivel de precios de los activos en relación con su valor fundamental ya había cruzado un punto sin retorno, creando una frustrante sensación de fatalismo para muchos participantes del mercado con los ojos abiertos.

Décadas de tasas de descuento decrecientes han robado tanto valor del futuro que ya no quedan plántulas de crecimiento futuro para siquiera echar raíces. Por lo tanto, el problema aquí no es el ahorro en sí mismo, sino los pastos de ahorro específicos en los que los individuos están siendo apiñados. Ahorrar no es ahorrar si no se canaliza a depósitos reales de valor. Todo lo contrario, de hecho. La única manera de mantener los niveles de vida actuales requiere tasas de crecimiento perpetuas de los precios de los activos, que a su vez requieren más y más deuda.

Si el gobierno y los influyentes culturales normativos exportaran tal dinámica a las masas, ¿Cuál deberíamos esperar que sea el resultado? ¿Es la igualdad y la abundancia utópicas? ¿O es planificación centralizada, un mercado libre marginado y una actividad económica socializada? ¡Lo adivinaste! ¡Puerta número dos, Bob!

Fuente: Business Insider, CBS

Bloque tres: Matemáticas

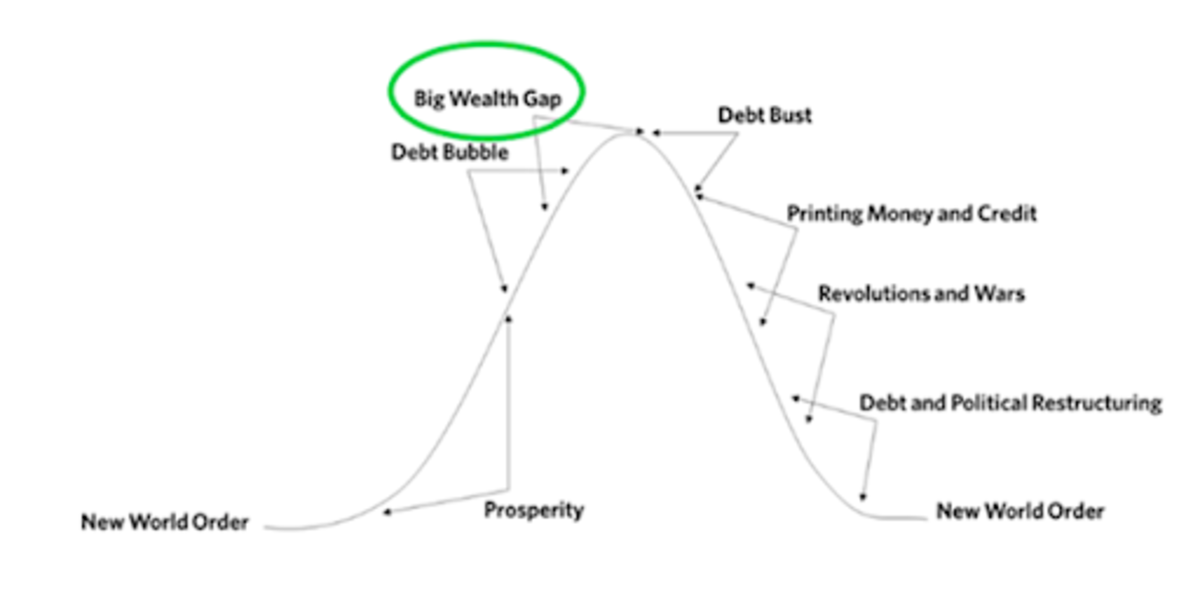

Una de las variables más influyentes que históricamente se ha asociado con el final de períodos de gran estabilidad y fortaleza ha sido la desigualdad de la riqueza. Si bien tal sesgo rara vez es el origen de un colapso sistémico, casi siempre es un síntoma de la decadencia, y con la misma frecuencia juega un papel en catalizar el punto de inflexión hacia la decadencia. Desde los mayas hasta el Imperio Romano, los Tres Reinos de China, los otomanos y las revoluciones francesa, rusa y china, la desigualdad de la riqueza siempre ha jugado un papel importante.

Fuente: Ray Dalio,”The Changing World Order”, capítulo uno

Este es un gran problema para la estrategia de la clase de inversores masivos. Esto se debe a que una meta de redistribución de la riqueza con una estrategia centrada en la inflación de activos es estadísticamente imposible de lograr.

Muchos defensores de esta nueva clase de inversionistas adoptan el enfoque de”combatir fuego con fuego”. Yes, asset inflation — driven by modern monetary policy — has been the prevailing impulse of inequality over the last several decades. Why should the average individual not be able to get their just desserts as well? Ethically speaking, I take no issue with such retribution to some degree.

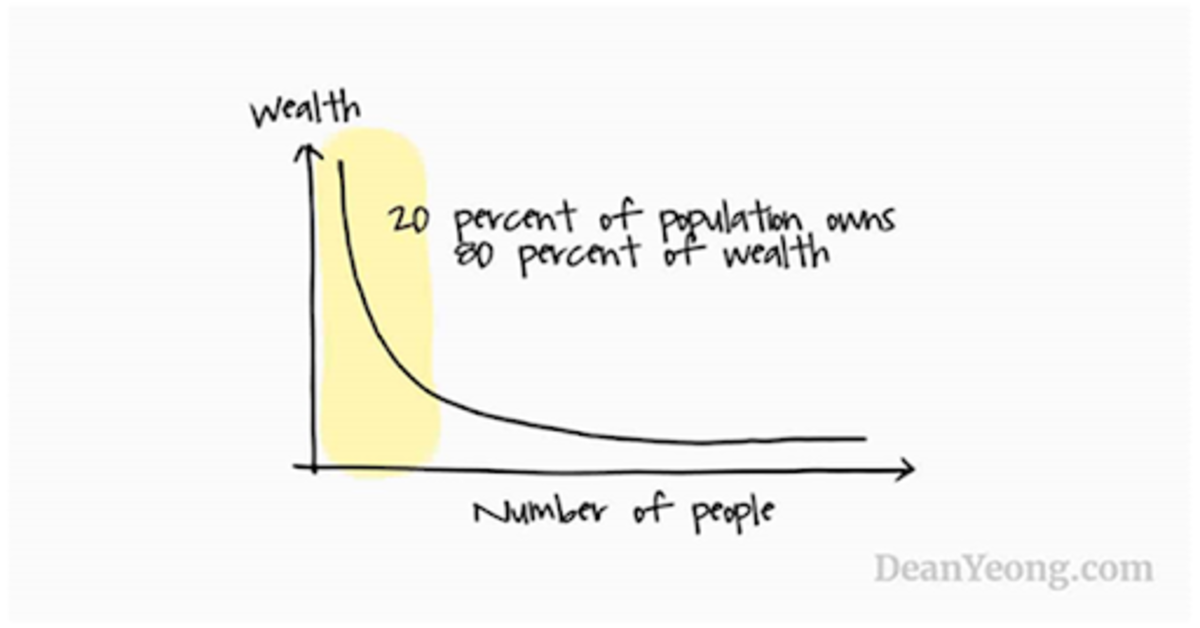

Unfortunately, it’s an illusion. The presiding growth curve that has been empirically witnessed as it pertains to wealth distribution has been found in the Pareto principle, a probability distribution whereby a small percentage of the sample group acquires most of the attainable value. Facets of this law, more colloquially known as the “80/20 rule,” are observed not just in wealth distribution, but prolifically throughout much of nature and human social environments.

We have experienced at least a half-century of Cantillon effects that have supported asset owners in exponentially outperforming relative to income owners. Even if we disposed entirely of such Cantillon effects and allowed the broader population equal access to financial assets going forward, and even if financial assets continued to generate historically anomalous returns, the “80 percenters” would never catch up. The reason for this is simply due to the nature of exponential growth curves as seen in the Pareto principle. Inequality would be maintained at the very least, if not continue its asymptotic expansion.

Pareto’s law: How asset inflation becomes a highly entropic state for wealth distribution, regardless of policy.

Source: DeanYeong.com

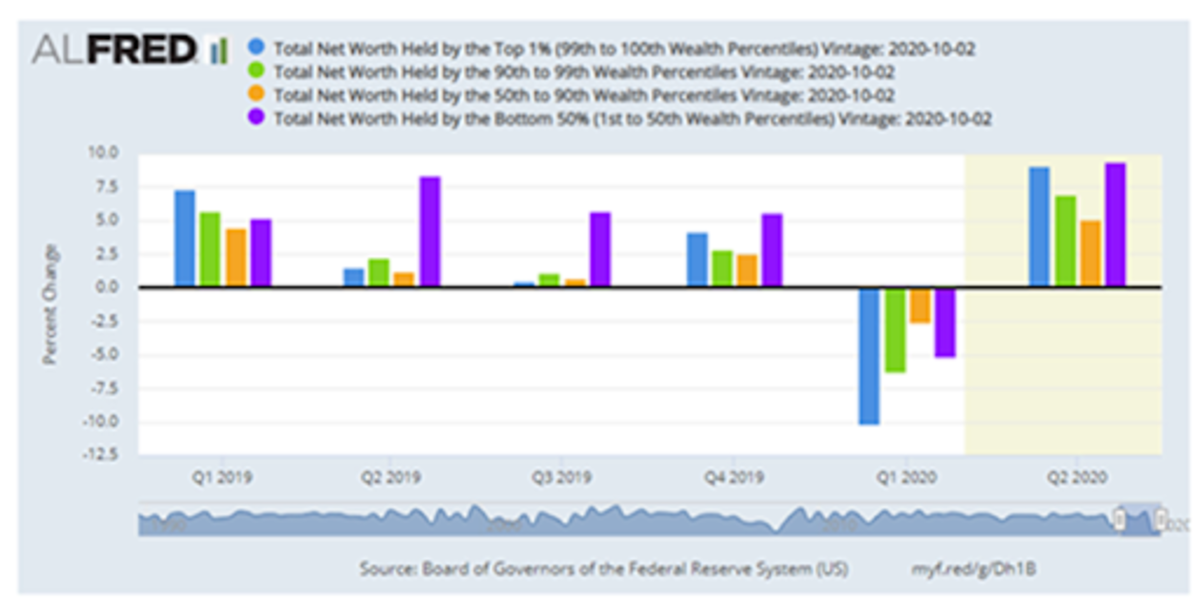

This Pareto probability distribution is exemplified quite dramatically after looking at 2020 as an outlier year, whereby the least wealthy percentiles actually saw the largest percentage improvement in wealth. However, while this is a lovely-sounding statistic for social media hype and political propaganda, it is purely a mathematical outlier caused by starting from such a low base and from such a low level of prior financial asset ownership.

Unfortunately, the banner year for the bottom 50% (purple bar below), did next to nothing to narrow the wealth gap from the top percentiles, as evidenced by the below chart.

Source: Federal Reserve

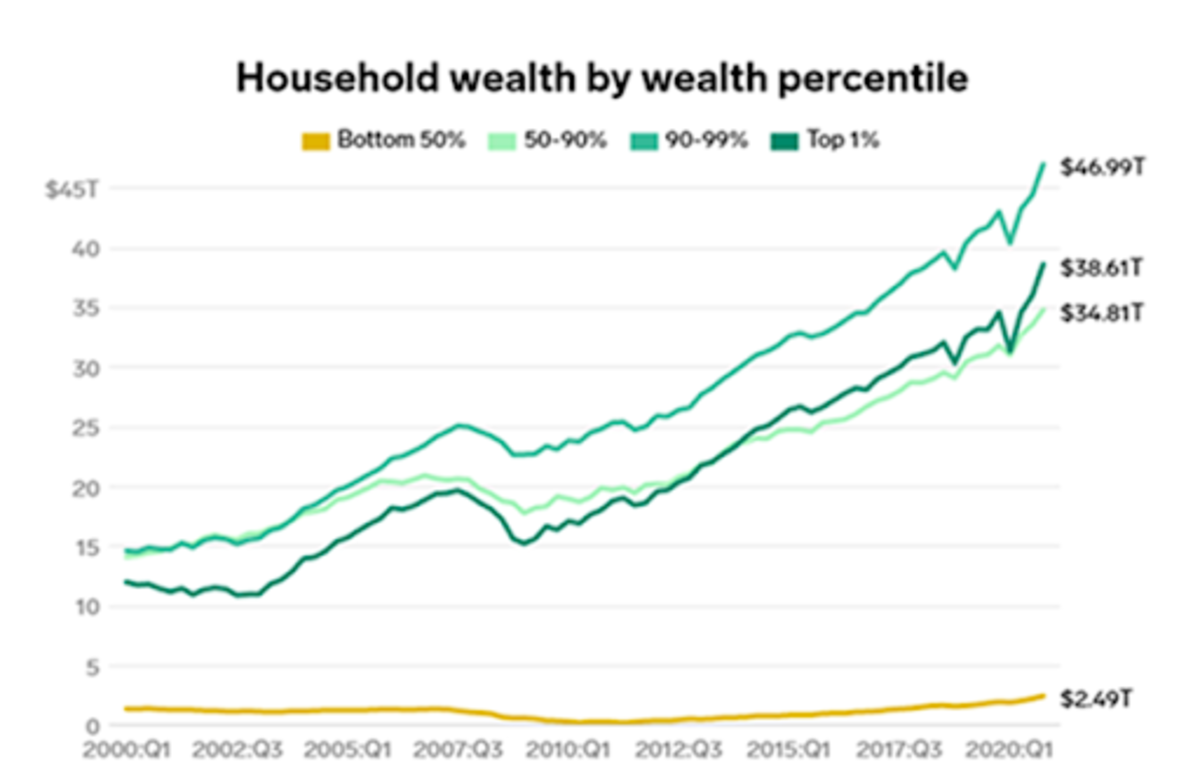

2020 did nothing to rectify the problems of inequality. In fact, inequality only got worse. Why would a continuation of asset inflation look any different in the future?

Source: Federal Reserve, “Distributional Financial Accounts”

If inequality cannot be corrected by the only policy tools available, the risks for social instability will only rise further. Ironically, when stability is threatened, this tends to only increase levels of centralization.

Have you ever been driving your car on a wet, slippery road, only to fish-tale unexpectedly? While our instinctual response would be to tense up and violently steer the wheel in the opposite direction to regain control, such a reaction would only worsen our dire predicament. One must steer into the chaos. Once control has gone, such a fate must be embraced, not opposed. This is the only way out. Further attempts at control only make matters worse.

Block Four: All Roads Lead To One Road, More Centralization

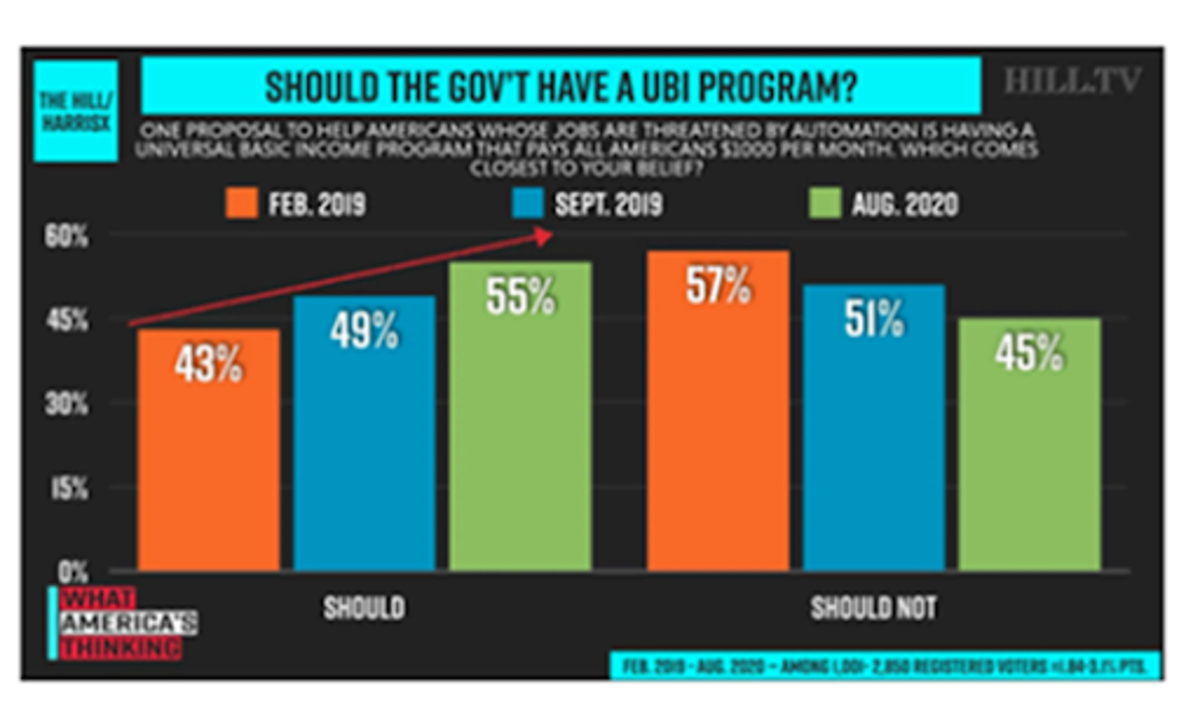

Once the inevitability of blocks one, two and three as stated above are appreciated, the path dependency of block four in our chain becomes absurdly apparent: Subsidizing asset prices through monetary debasement becomes the oblique way that society yields to ideologies like universal basic income (UBI).

UBI may end up in the very long run as explicit social welfare programs, or “helicopter money.” Of course, during COVID-19, we saw some discreet examples of this, turning something merely theoretical into a tangible part of the societal zeitgeist. However, it is a mistake to assume a linear path, that such policy will now settle as the initial and most effective vector for such policy going forward.

A more frictionless pathway would be the mechanism outlined above, whereby social welfare can be extolled circuitously. The brilliance of such a policy approach is that it would not require any incremental pieces of legislation, and no constitutional alterations to property rights. There are no foundational legal constraints. This implies that our current institutions have the power to accomplish such social welfare goals today.

One could argue that some changes would certainly make these aims easier to administer, like augmenting the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 and expanding the powers of the U.S. Treasury Department. However, the key point here is that such change is not required. If the reader finds this too far fetched, I would recommend listening to the taped conversations between ex-President Richard Nixon, and then-Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns. It has happened before in this country, and in less dire circumstances.

Source: TheHill.com

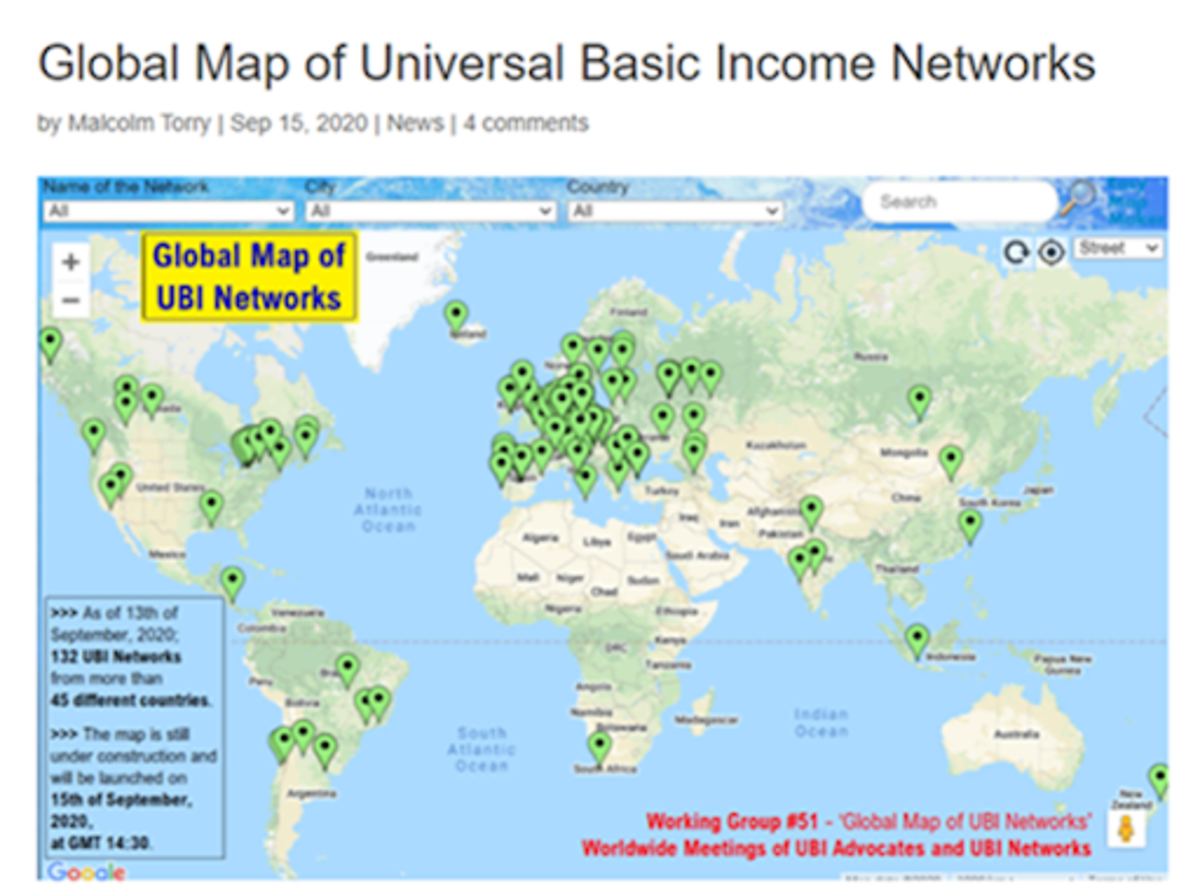

UBI advocates are here, and they have their own network effects:

“The map references not only networks with the sole purpose of advocating UBI, but also all organizations (networks, foundations, platforms, political parties, working groups within political parties, societies, study groups, etc.) that advocate for UBI.” Source.

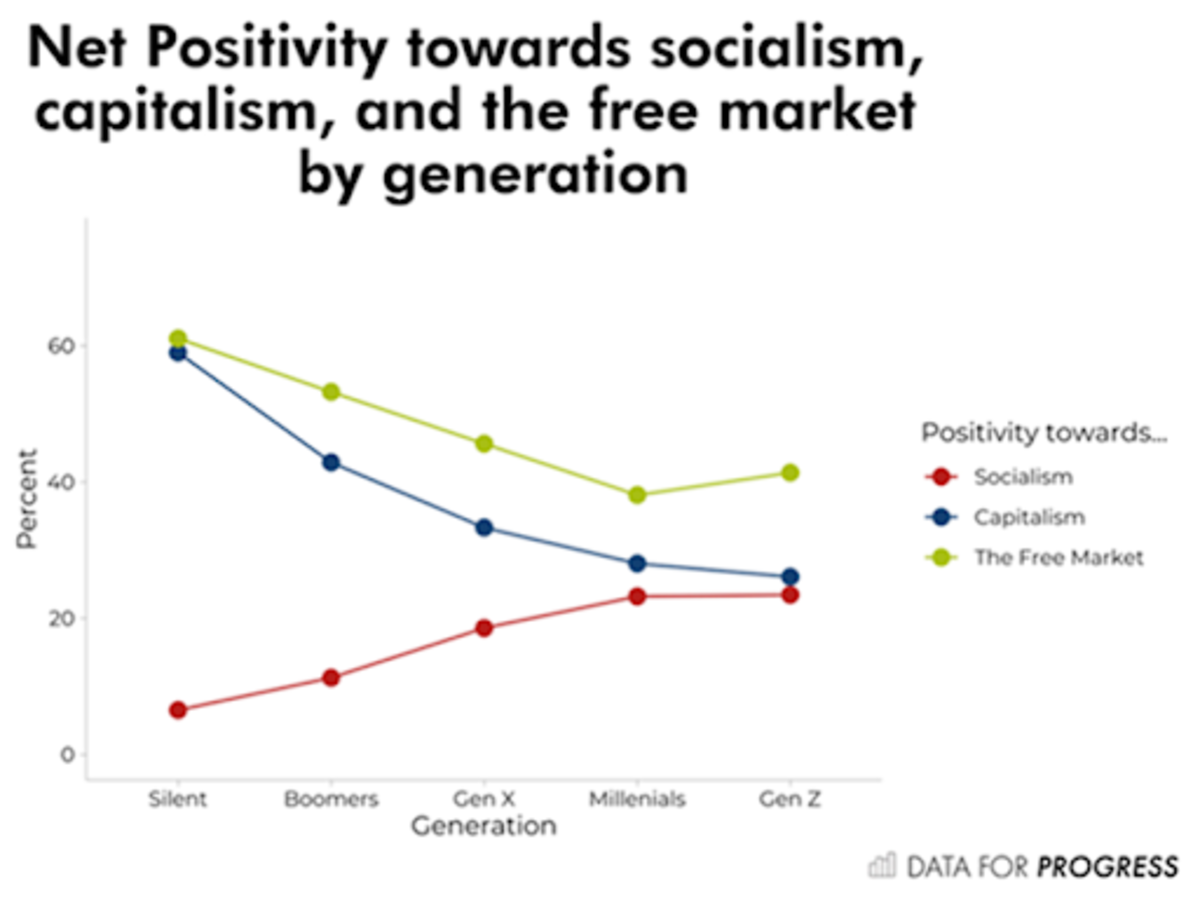

American openness toward socialism, and a commensurate disdain for capitalist ideals, has increased dramatically over the last four generations. This has been well documented with recent generations, particularly millennials, but it is important to recall that such a trend has been consistent well before that, even with the boomer generation relative to their parents and grandparents.

This is rather alarming when one considers that this generation has been the biggest beneficiary of financial asset prices (coincident with the full embrace of the fiat monetary system) of any generation in American history.

A Quick, “Passifict” Detour: Passive Investing Socializes Capitalism

Bitcoin may be humanity’s historically most perfect manifestation of a pacifist revolution, but passive investing is also a revolution, only with completely opposite implications.

Historical analogues are always dangerous, and each generational crossroads exhibit unique characteristics that can change the entire spectrum of outcomes. However, as a reference point, current trends reverberate with echoes of previous centralizing efforts designed to redirect our collective future and shift the public behavior, reminiscent of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “new deal,” as well as Nixon’s “great society,” or even going back to German Chancellor Bismarck and his social welfare policies in the 1880s, which greatly enhanced the Second Reich’s military capacity.

Passive or indexed investing vehicles such as exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are yet another example of this shift toward a “mass investor class.” While such a trend may seem innocuous, it is cultivating the seeds of enormous societal change.

As discussed by Inigo Fraser-Jenkins, a highly-regarded maverick quantitative equity strategist at Wall Street firm Bernstein, passive investing can be compared to Marxism. This may sound hyperbolic, but unfortunately, I believe he is on to something important here, the point being that the democratization of capital markets by way of ETF proliferation and other passive investing products inadvertently leads to a socialization of capital.

It would all but complete our societal transgression from liberal democracy to social democracy, a trend that has been gradually underway, but accelerating over the past 75 years. Fraser-Jenkins compared passive investing to other societal externalities like the tragedy of the commons, whereby behavior that may be optimal for the individual investor can be quite negative for the aggregate society when all actors behave the same way (we will return to the problem of the commons later).

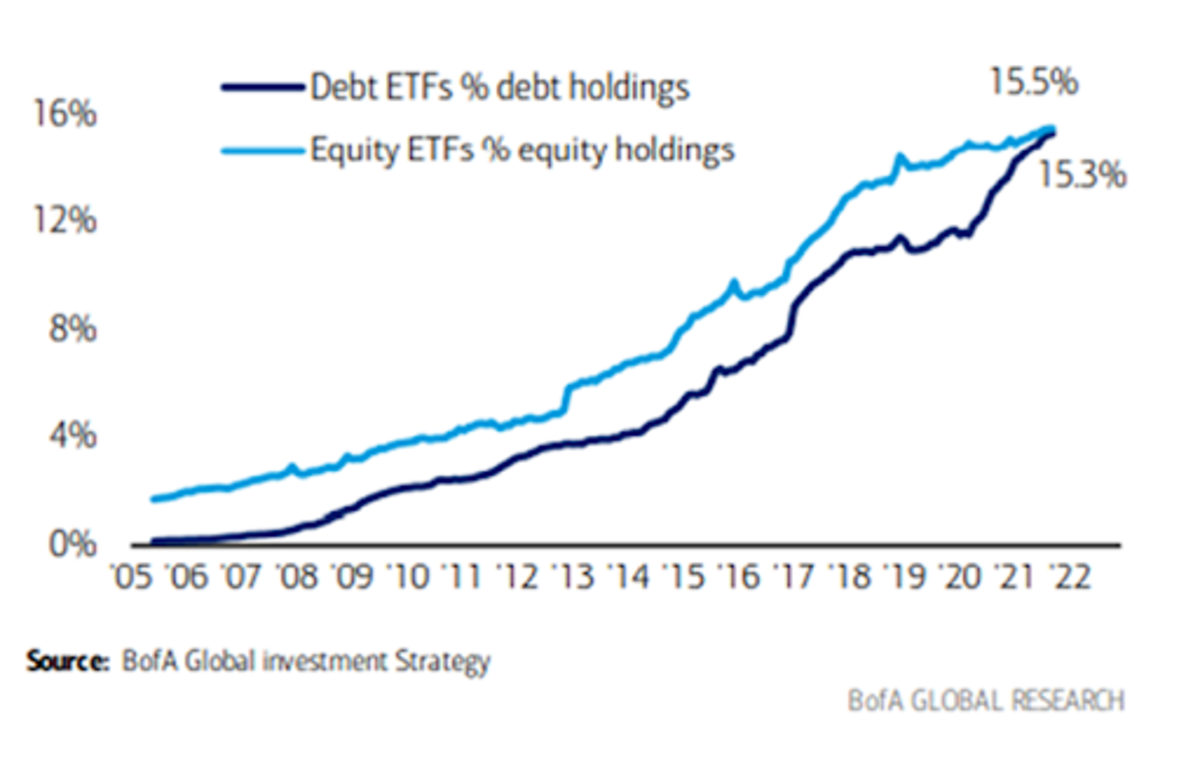

The unfettered expansion of passive investing does not look likely to subside any time soon. This is especially obvious when one simply looks at the below chart, or even at the hiring behavior on Capitol Hill, like the large representation of Blackrock alumni acquiring key roles in the current White House administration. Blackrock is the number-one manufacturer of passive investment vehicles in the world, with over $1.8 trillion in assets under management (followed by Vanguard in second place at $1.2 trillion).

Additionally, ESG and clean energy investment mandates further this shift, creating new products to bundle into thematic passive investment securities. Such bundles make it easier for ESG-approved companies to redirect capital away from those companies that do not fit the homogenous definitions prescribed. To be clear, there is nothing intrinsically bad about incentivizing cleaner energy and more sustainable economic practices. Of course, this is a good thing! However, when rules for such behavior become formalized, complex, and sometimes arbitrary and naively general, they impinge upon the competitive dynamics of free markets that would accomplish such goals more effectively.

Instead, such rules generalize the flow of investment, compensating those market participants best suited to game such a system. The new game defines the winners as those best able to adhere to the appropriate definitions as a means of acquiring low-cost capital. In a road paved with good intentions, we potentially end up in hell, robbing free markets of innovation, nuance, and differentiation. We write new rules of the game, rules that thoughtlessly increase centralization.

Mike Green, a distinguished researcher of passive investment stated back in 2020:

“Of managed assets, [passive investment] is now greater than 50% [and over 40% of total market capitalization]. That split though, is not uniform across demographics. Millennials are almost 95% passive. Boomers are only 20% passive. For the vast majority of millennials, their only exposure to the market… We make a lot of hype about things like Robin Hood and stuff, but the actual assets are tiny. The vast majority of the money that they’re getting is actually just going into things like Vanguard target-date funds.”

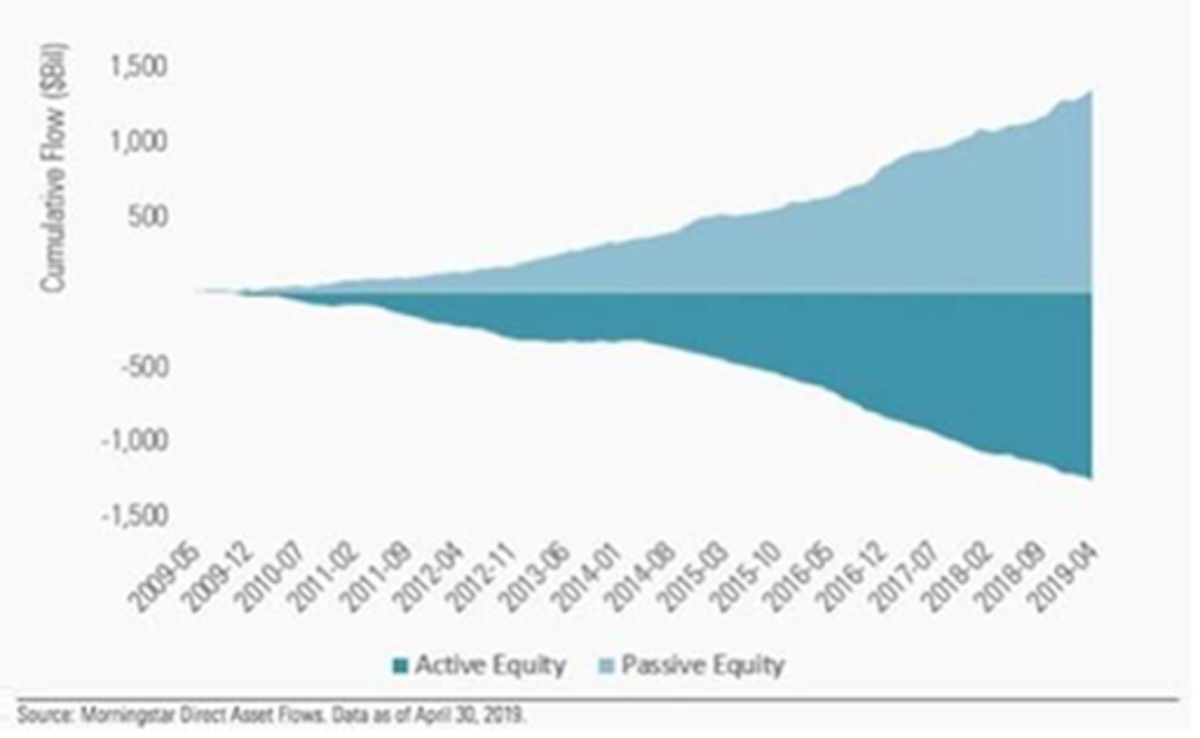

Active equity managers have seen outflows every year and passive investment vehicles have seen inflows every single year since 2006. And this trend is only accelerating:

Source: Morningstar

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Bank of America’s private client ETF holdings as percentage of assets under management (AUM). A hard trend to fight:

Source: Bank of America, Michael Hartnett

The passive singularity: Millennials have 95% of their retirement savings invested in passive vehicles. What is the logical conclusion of this freight train?

“One of the challenges that gets created as passive becomes a larger and larger share is that there becomes no discretion. There is no consideration of should the incremental dollar go in in the exact same fashion, right? That passive player has no instruction to sell. You exhibit increased inelasticity in terms of each incremental dollar that goes in. Imagine a scenario in which 100% of the owners of a company were passive and you tried to buy a share. There is no price at which they would be willing to sell to you unless they received an instruction from their end investors saying to sell shares to you. Prices could theoretically become infinite on that type of dynamic. Eventually, you would expect somebody to respond by saying, ‘All right, I will sell an additional share to you.’ Traditionally, that’s been accomplished by price-sensitive or return-sensitive discretionary managers who say, “Okay, this price is unwarranted by the fundamentals. Therefore, I’m willing to sell some of these shares to this person who’s expressing, in my view, an irrational demand for these shares.” If that demand is so strong and it gets absolutely extreme, people can synthetically create shares by shorting, but that is incredibly dangerous to do, an environment in which stocks are exhibiting this reduced elasticity.” –Green

The mass investor class faces a big incentive problem: What does the internet, digital property, and a tragedy of the commons have in common? Our retirement accounts.

The dismantled connection of choice from the capital allocation process brought about by passive investment proliferation has implications beyond the clear destruction of price signals. This is no small statement. A destruction of price signaling is as destructive as things can get for a capitalist system. Prices are the main form of communication we use in society to make appropriate economic decisions and choices. Its dissolution is of existential importance.

However, there are other problems to consider from this evolution of behavior as well. Ever since the runup to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, and at an accelerating pace since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, society has become more aware of the vast concentration of power that the internet giants and social media platforms carry.

Pockets of government and pockets of new and growing cultural progressive movements have quite easily influenced and incentivized these platforms to actively censor speech in our democracy. This is not a political statement, and this is not a judgement about the people being censored, but merely a factual observation about a key tenant of our democratic institutions. If the U.S. Constitution can be likened to the “core protocol algorithm” dictating the manner in which our collective network operates, this is a clear attack on one of the most vital rules of the protocol. How can we so readily dilute our core principals?

First, network effects are powerful. The ability of the internet companies to sustain and grow off individual resources, with extremely low detachment rates, cannot be underestimated.

How did this come to be? A failure in timing. As is often the case with disruptive technology, its usage preceded an appropriate infrastructure to handle it. Unfortunately, the Byzantine Generals Problem was not solved before the advent of the internet. Consequently, we have been suffering the consequences that a lack of enforceable property rights leads to in a digital world. A winner takes all society.

This is what the internet got wrong. You didn’t own anything. No one had any stake on the internet. Instead, value has been extracted by those who figured out ways to own the on-ramps and access points to the internet instead.

This group has become the “landlord class” of the internet, and the vast majority of value proffered by the internet and its myriad innovations of social communication has been funneled through this layer. The consequence, of course, has been more inequality, more surveillance and control, and more concentration of power. Further, we’ve witnessed a trend toward a reduction of quality of information. There is a diffusion of responsibility that engulfs the internet when ownership is so opaque and ephemeral. We are incentivized to create more noise than signal because when no one owns the land, there is no incentive to be a steward of that land to ensure its long-term sustainability, utility and productivity. Instead, the incentives align so as to be solely transactional. The more information one can manage, control and recapitulate, the more one can develop network effects and externalize the social and economic cost of a system that produces excessive noise and underproduces enough structured signals that could offer synergistic benefits across societal planes. That cost is shared by all of society. It’s a tragedy of the commons. All because the internet couldn’t address digital property rights.

The second issue here is that network effects also impact passive investing. Most passive vehicles are ETFs, that are indexed and weighted by market capitalization. The bigger you are, the more capital you attract. Size matters, aptitude and productivity do not. This takes us back to the Pareto principle and the 80/20 rule, setting the stage for increasingly non-linear distributions of capital. And in a world where access to low-cost capital is a massive competitive advantage, we end up with an obvious outcome. The big continually get bigger, and the small get only smaller. Or worse, the upstart disruptors may never have a chance, and we would never even know what could have been.

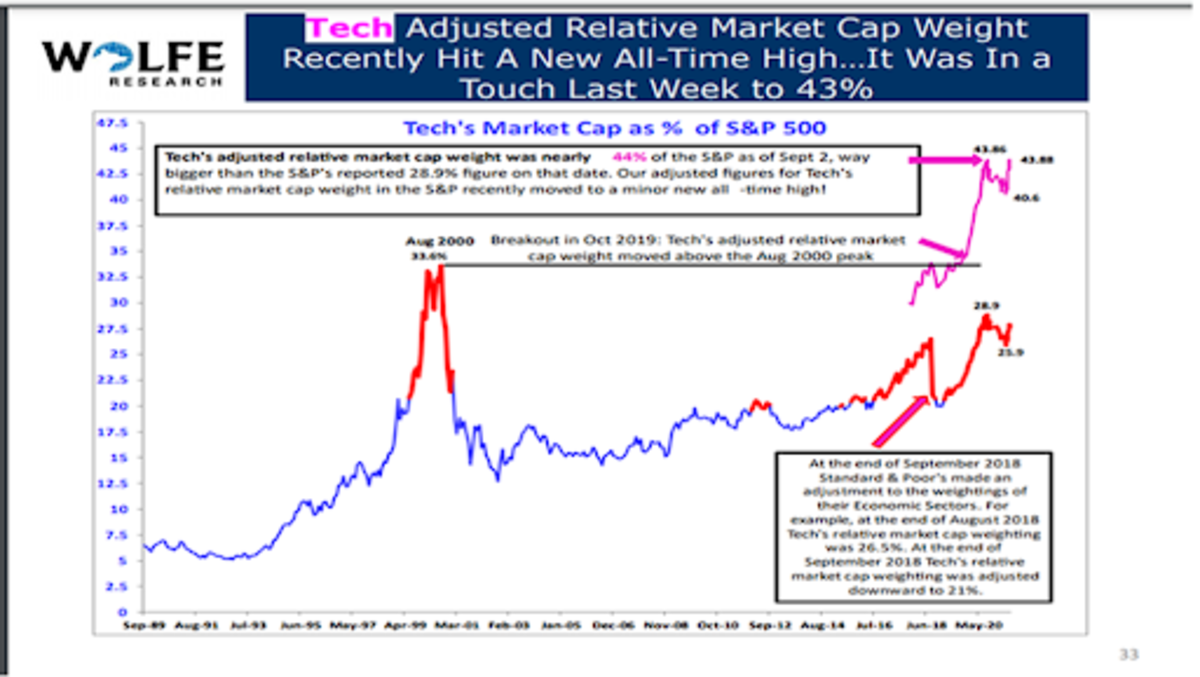

That brings us to the present, where just six behemoths have a near majority control of the entire equity market. Most investors do not blink at this statistic any longer. Professional investors have been numbed to such lopsidedness. However, imagine if such inequality persisted within the domain of political parties? In democratic institutions? In your childrens’ classrooms? But the real question we need to start seriously and honestly asking ourselves is this:

If the below chart only becomes even more extreme in its weighting distribution, and if our collective wealth is increasingly tied to the index it represents, what will our incentives be as the companies involved become even more centralized?

About 45% to 50% of our savings are tied to companies that could be actively censoring us, and indirectly eroding the very principles of the system that allowed them to prosper. This share of our savings will only grow further. Will we object? Ciertamente lo espero. But so far, there is little evidence to support that aspiration. Unfortunately, passive investing, alongside a mass investor class, is likely to only help internet platforms and capital markets centralize further.

Major stock indices are mainly just six names now: Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft and Nvidia, totaling 42% of the equity market.

Source: Wolfe Research

Block Five: All Roads Lead To Zero

What happens when zero volatility is the new equilibrium?

After our modest digression into passive investing, let us now return to the last block in our chain. The final and most deadly flaw in the chain reaction socializing financial assets relates to volatility and the cost of capital. Mathematically speaking, publicly-administered financial markets that demand continuous appreciation, distributed broadly and without diversification, will require volatility to trend toward zero over time.

A simple law in financial markets, when assessing an asset’s volatility (as measured by its standard deviation of returns over a given period), is that the more vulnerable to uncertainty an asset is, the less it can absorb volatility. This is why, for example, equity investors are generally willing to pay lower valuation multiples for cyclical or economically-sensitive sectors relative to secular growth or defensive industries. These types of companies are more vulnerable to unforeseen events. When our financial markets are a tool of policy rather than an expression of free market capital allocation, we eventually become incapable of withstanding any uncertainty. And manipulation to affect policy outcomes would be the only way to ensure uncertainty’s suppression. If successfully orchestrated, volatility must eventually collapse toward a zero bound to accommodate this.

As our centralized debt trap expands in circumference, the risk-free rate must also trend toward zero, as has been the case over the past 40 years. Over time, the consequence of this could even be the elimination of the need for a private sector.

This last section is essential to our thesis, as it is the bridge that transports us from the current transitional sandwich era where we find ourselves juxtaposed between centralization and decentralization. This is the last stop on this transitional train as we push relentlessly down the path toward a more authoritarian world order. Given its level of importance in our story, it requires some more detailed explanation.

Centralization As A Black Hole: The Volatility Singularity

Source: Disney, Pixar

What is the volatility singularity? Previously, we have established the logical chain of cascading events that are required in our world’s existing model.

Debt must go up, so stocks must go up. Thus, rates must go down, so volatility must go down. When this happens debt will logically go up, leveraging the system even more, so stocks must go up to prevent collapse and inflate the debt bubble with a greater equity cushion… (stop for breath)… So, rates must go down again until zero, so volatility must go down until zero.

Volatility collides with zero. Everything goes to infinity. Yippie! The transcendent state where the difference between nothing and everything gets very fuzzy and rather philosophically confusing. Just as observed in the case of black holes, where physics starts to behave mysteriously and spooky as one approaches the event horizon, so too do economies. Things start to get pretty eerie as we approach the zero point event horizon in volatility.

Thinking about the problem in the following simplified manner may be helpful:

Anything divided by zero equals infinity. Financial assets returns are a function of volatility. A common formula used to calculate risk-adjusted returns is called the Sharpe ratio, which is an asset’s return during a given period, minus a market risk-free rate, divided by the investment’s standard deviation of returns. If volatility is, for all intents and purposes, equal to zero, so too is its standard deviation. Thus, we end up in a confounding situation in which excess returns are divided by nothing, and therefore magically become, well… everything.

Image source. Source of quote: Kurt Vonnegut, “Slaughterhouse-Five”

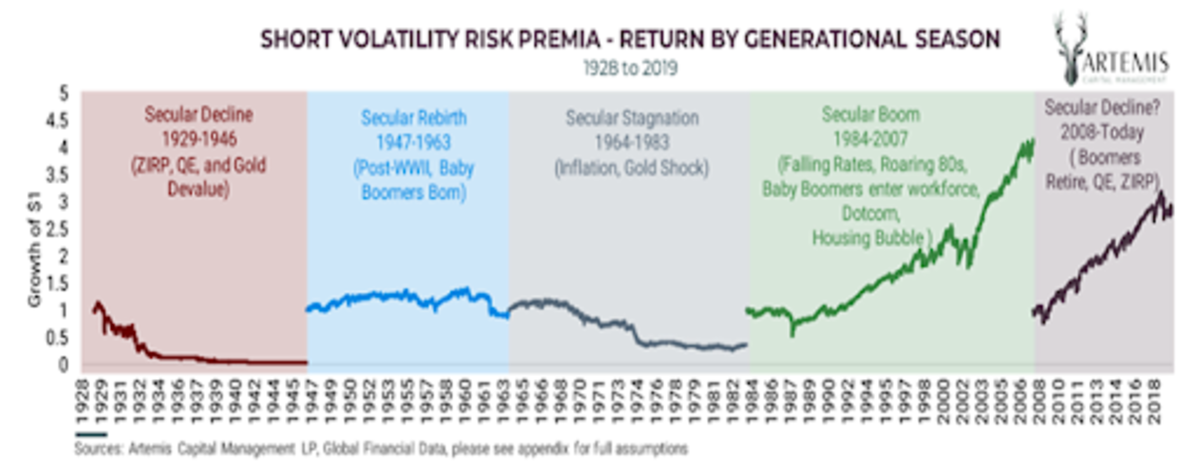

As macro volatility fund manager Christopher Cole excellently laid out in a 2020 piece titled “The Allegory Of the Hawk And The Serpent,” an investment strategy designed to short volatility, or benefit when it decreases, experienced temporally anomalous returns since the early 1980s, right when the financialization of Wall Street took off exponentially, and right as Alan Greenspan et al. began a campaign of moral hazard, at a time known as “The Greenspan Put.”

The stock market and nearly all financial assets in aggregate then become just a mere proxy for this “short volatility” expression.

Source: Artemis Capital, @vol_christopher

An Endangered Golden Goose

Cole, like many others, believes this period of declining volatility is mean reverting and must therefore repeal its nearly 40-year journey. While certainly possible over a cyclical short term time horizon given the magnitude of the move, a spike in volatility is unlikely to be palatable for any sustained period. The reason, as you might have guessed, is because of the deterministic nature of acceptable outcomes laid out above. The violence to the system that a spike in volatility would require would eviscerate so much wealth, so many debt obligations, that the policy response would be equally violent. Such a response is all but guaranteed because the crisis would be existential for those in power.

This outcome becomes more assured each day that goes by with greater reliance on financial assets to lift us into the future, each day that a citizen puts their first dollar of savings into such a system, and each day that another dollar is diverted away from new capital expenditure in favor of being recycled instead back into the existing sinkhole.

Below is a graph of the realized one-year volatility in the Dow Jones Industrial Index going all the way back to 1895. The pre-WWII average of this proxy for stock market volatility was about 20%, witnessing only one to two “black swan” spikes during a 50-year span. Meanwhile, the post-WWII average has been closer to 14.5%, with three black swan events observed only within a 30-year period!

This graph gives us two important pieces of information:

Volatility is trending lower over time. A move from 20% to 14.5% may not sound significant, but this is a nearly 30% decline in average volatility. The positive effect of such a shift has on underlying asset prices cannot be overstated. A system of declining volatility has come at the heavy cost of greater susceptibility to bouts of near-disastrous black swan events, external and internal shocks. And these events are not capable of being permitted to clear the imbalances that caused them, to self correct, as the system would break before such catharsis could be attained. Instead, each successive crisis forces policymakers to intervene at much lower levels of volatility than in the pre-WWII era. This of course fuels greater abdication of responsibility, which fuels the next crisis as we rinse and repeat, racing toward zero.

Source: @LudiMagistR, Bloomberg

Centralization Is A Fabergé Egg: Systems Which Require Stability And Efficiency Are Always Extremely Fragile

I recently came across a white paper authored by Ben Inker and Jeremy Grantham, famed hedge fund investors at GMO. They conducted a data mining project and looked at the prior periods of frothy financial markets like the 1999 to 2000 period, and similar historic periods of strong performance and excess returns. They were surprised to find that it wasn’t earnings growth, the level of real interest rates, or even GDP growth that mattered during such periods of excess and euphoria.

Instead, they found three consistent variables that were always part of the equation:

Atypically high profitability for one or some segments of the economy (this is finance speak for maximal efficiency rather than maximal productivity)The stability of GDP (as a proxy for overall economic activity)The stability of the rate of inflation

In short, markets care not about actual levels of growth, inflation and profits. Predictability is what matters. A financialized system and a mass investor class requires stability and loathes uncertainty. Said differently, our system of monetary inflation rewards monopoly formation, values efficiency over productivity, and requires reduced volatility to sustain itself.

Given that volatility is a natural phenomenon of any free system, suppressing it requires external and artificial forces. It requires a central authority to manage the system and to solve for low volatility. Our central bank policy of monetizing moral hazard is evidence of this. Moral hazard from this prism is simply a function that solves for low volatility, at all costs. And there are a lot of costs.

Moral hazard visualized: Credit Suisse Fear And Greed Index. Source: @LudiMagistR; Bloomberg; Credit Suisse

The Difference Between A Medicine And A Poison Often Comes Down To Dosage

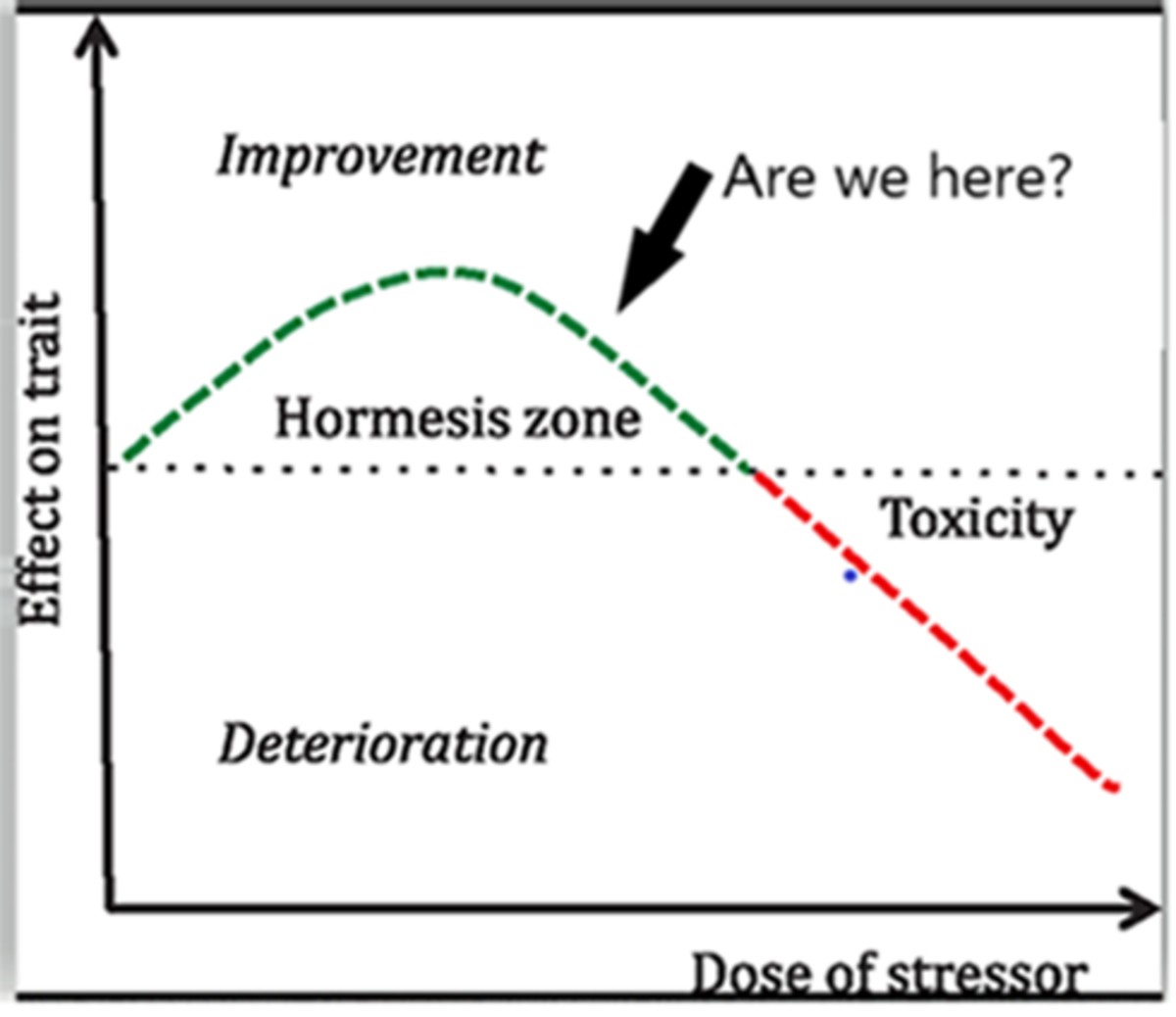

While the importance of gains in efficiency are indeed a requisite aspect of technological progress as well as a tremendous generator of wealth for those providing such efficiency gains, there is always a trade off. A great example of this is the Bitcoin block size war of 2017, as well as the many utility protocols proliferating the crypto universe, optimizing for network throughput at the cost of much weaker decentralization. The irony is that the many use cases of blockchains become completely obsoleted without decentralization. Efficiency is great. It’s exciting. It often is associated with innovation. To a point.

Where is this point?

Any marginal gain in efficiency requires a marginal loss of resilience. Given that resilience is vague and incandescent, a decline can seem harmless until it suddenly breaks completely. This means that the relationship between efficiency and resilience is non-linear. There is always a point on the curve where the benefit of efficiency gains become precipitously overwhelmed by the cumulative trade-offs.

Source: Nassim Taleb, “Antifragile”; @LudiMagistR

Ok, fine. Let’s agree that the financial system is in fact becoming more fragile. What does this have to do with centralization of power? Shouldn’t a fragile system lead to the dissolution of power?

Short answer? No.

Less short answer? A centralizing power depends on vulnerability to validate its own existence. As the costs of centralization mount, is becomes existentially vital for an authority to lay claim on the sole ability to medicate the very ailments it fabricates, so as to traverse unstable times unscathed. Fragility maintains power. Power thrives on fragility.

Efficiency Is A Great Barometer Of Where We Are In The Macro Cycle

Why? Efficiency naturally peaks at the end of a regime. By the end of the regime, everyone assumes the cycle to be permanent because no one remembers a different world. We succumb to recency bias, forget history, and inadequately discount the inevitability of change.

Efficiency, fundamentally, is a way of optimizing processes or work to a specific environment. By the end of a regime’s lifespan, an environment’s self-selected economic participants have naturally maxed out adaptations to that one environment, having gone “all in” on its defining characteristics.

Thus, like a grain of sand placed on a growing sandpile, all that is needed is just one inopportune shift and the whole system cascades down with surprising fragility. A meteor hits, and we are cold-blooded, energy-consuming goliaths. Good luck with that!

We’ve of course seen this story time and time again throughout history, both at biological and evolutionary scales when diversity is overcome by uniform specialization, and throughout the annals of human history. This is one explanation as to why empires always eventually fall. Their successes eventually become their weaknesses. Efficiency helps fuel dominance in a world that values power as a function of resources, but it leads to dangerous deficits in resiliency that inevitably make them easy to destroy. This is also why empires are often built over long periods of gradual ascent, but often fall precipitously. Non-linearity.

Thus, somewhat counterintuitively perhaps, periods of maximal efficiency will precede periods of instability and upheaval.

An Obituary For The Private Sector

Now, let us return to volatility.

As the boulder of zero volatility and a fully-managed economy slides precipitously toward its Newtonian fate, there will slowly materialize some incredibly powerful implications for the structure of private property rights. This is because zero volatility and a required real risk-free interest rate held at zero or negative levels will logically push the aggregate cost of capital to extremes.

When there is no risk of material loss for capital, there becomes no discrimination as to how to invest it. The decision-making process becomes tied much more to government policy goals, cronyism and bribery, and other characteristics very similar to those of communist systems of governance. The corporation and the entrepreneur lose their utility in this world.

The birth of the modern corporation can be traced back at least to Adam Smith’s 1776 classic, “Wealth Of Nations,” interestingly published the same year that colonists here in America sought independence.

In this work, he lashed out at the “business association,” his era’s version of the state-owned companies, or the precursor of the “military-industrial” complex, or in China’s case the Sovereign-Owned Enterprise (SOE). These were institutions like the British and Dutch East India companies in Smith’s time.

He argued against monopolist business practices, which in turn paved the way for the legal autonomy of business outside the direct control of the government. As far back as 1844, corporations began earning the status of “personhood,” eventually granting them 14th Amendment rights in 1886. This paved the way for the evolution of corporate oversight toward the domain of the court system and not that of the executive and legislative branches.

The point here is that while we sometimes think of corporations as gatekeepers, monopolists, greedy beneficiaries of consumerism, debt and inflationary growth, these adjectives describe their failures within our current system, not their original purpose. The corporation was originally designed to bestow greater power to the entrepreneur and decentralize power away from the state.

By providing legal protections like limited liability, the corporate structure allowed for individuals to combine resources without unmanageable personal risk, which in turn allowed for the competitive acquisition of capital for investment. So, when the cost of capital and the risk of capital become immaterial, the existential purpose for the corporation becomes difficult to justify. And so the economy centralizes further with the erosion of one more source of decentralization.

What is so exciting about Bitcoin within this context is that it replaces the vacuum created from an impotent corporate private market structure with something much more decentralized and much better suited for the evolving digital information economy. It helps an increasingly interconnected economy divide labor beyond its current stalemate.

Bitcoin is a medium of specialization. Corporations were invented to be a specializing spoke of private capital, allowing for greater and more scalable division of labor. Unfortunately, in a world where the digital realm is becoming the majority sphere of economic activity, where individual property rights had not been assured prior to Bitcoin, the corporation instead has more often become a rent seeker, a bottleneck for competition, and a gatekeeper of digital property. This has had the perverse effect of decreasing our collective ability to specialize. Bitcoin solves this problem.

However, I am getting ahead of myself. We will get into this exciting potential in greater detail in part two of this series.

A Dangerous Cocktail: Why The Pareto Principle Matters

As the world becomes more interconnected, relationships become more “Paretian,” and less “normal,” or mean reverting. This is because the Pareto principle has shown empirically that complex systems often demonstrate extremely asymmetrical distributions of effect. Effects that only magnify as the system grows larger.

Prior to the interconnectedness driven by technologies and the scalability of digital networks, such Pareto effects were only discernible at ultra-large scales or where the complexity of the system was much larger than witnessed in everyday life, in fields such as macroeconomics, astronomy, geology, ecology and theoretical physics. But over time it is being appreciated just how pervasive this Pareto dynamic truly is.

In the business world, it has been shown that roughly 20% of customers often produce 80% of a company’s revenue. Eighty percent of a company’s output, likewise, is often generated by 20% of its employees. The pattern is found in many random systems. Eighty percent of highway accidents occur at 20% of the path traveled (near home), 80% of the cost of building is spent on 20% of the structure, and 20% of the world population is responsible for 80% of the pollution. The list could go on. But this simplified 80/20 rule actually understates the impact, as it is simply an approximate guide, the map rather than the road itself.

In fact, this 80/20 ratio can often turn into 99.9999/.0001 quite easily. Take a simple example where the square root of the total nodes in a given network is the number of nodes that are deemed to have the most measurable impact on that network. If we start with 10 nodes, we have about three nodes fulfilling that role, or about 30%. If the network grows to 500 nodes, we get about 22 nodes, or less than 5% of the network. If we end up with 500,000 nodes on the network, the figure would be about 707 nodes providing that impact, or a stunningly small fraction of 0.1%. Non-uniformity scales exquisitely.

As we begin to see, the Pareto principle is powerful in large systems, and is so important today as the world interconnects exponentially and in increasingly fractal patterns. The bigger the network, the more extreme the variance. Decentralization is a natural outcome of network building, especially if allowed to flourish without interference or external exploitation. Therefore, it is a logical conclusion as a general principle that decentralization increases variance and begins to break down previous patterns of mean reversion that are so characteristic of normal probability distributions.

Conversely, centralization craves more uniformity. Otherwise, there become too many outliers in the herd to corral, and the system becomes unmanageable. As networks proliferate, governments increasingly are driven existentially to ramp up the use of power and coercion against this natural force.

Not only is the world experiencing greater dispersion of outcomes, it is also changing at an increasingly faster pace. Raw data is pouring torrentially down upon us, overwhelming our neural capacity more each day. We are confused, overwhelmed and looking for anchors, answers, and authority.

“Black swan” or “tail risk” events, by definition, are not predictable by any model. Otherwise, they would not be black swans. Models often give us a false sense of stability, understanding, and confidence. The renowned behavioral economist Daniel Kanneman has shown that even when we are given statistical predictions that we know to be spurious, we embarrassingly cannot help but feel assured and make more risky decisions based on such irrelevant data.

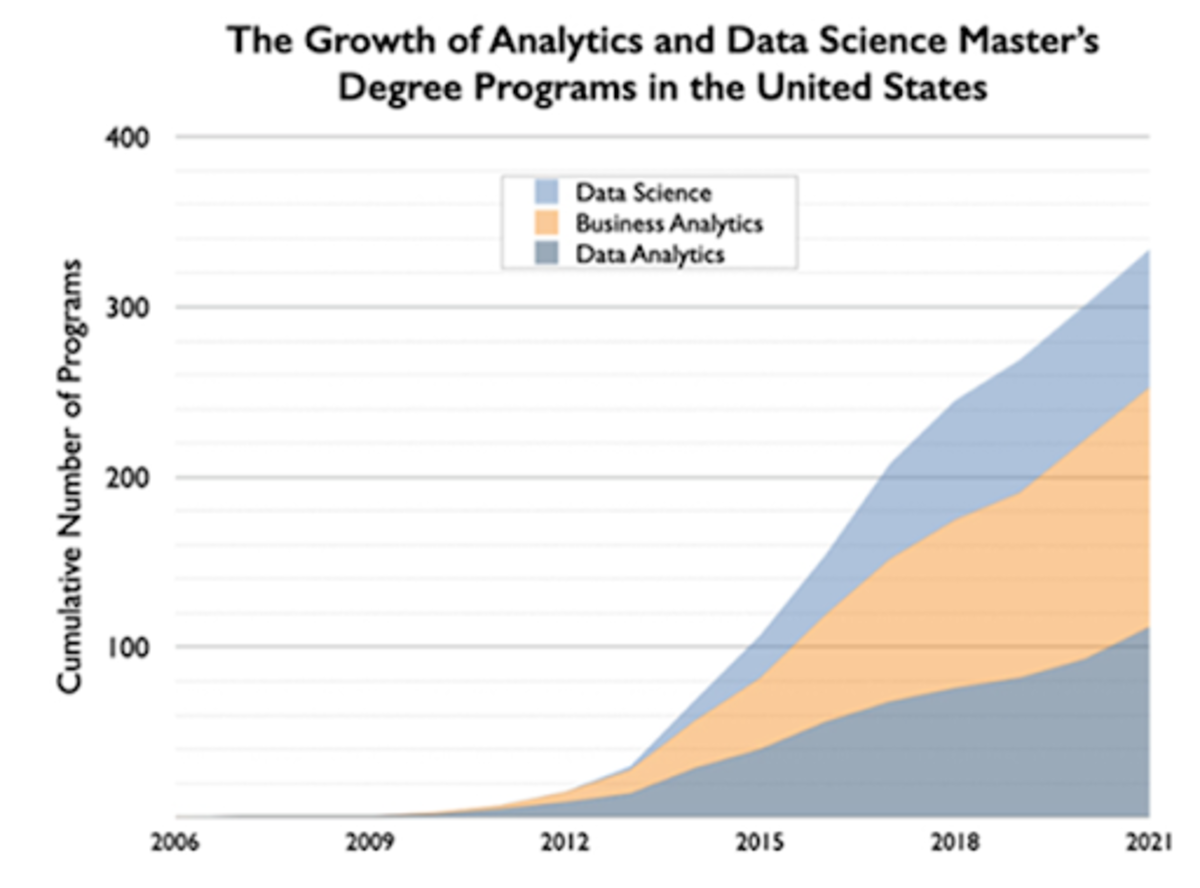

Nonetheless, the pace of change and data dumping has inspired us to overly romanticize and revere data accumulation, prediction, and data modeling techniques. We even have new professions that have popped up to deal with such issues, often aptly referred to as data “scientists.” Most major universities over the past decade have added degree programs for data science and it is now one the fastest-growing programs in academia.

Source: Michael Rappa, Institute for Advanced Analytics, May 2021

Now, let us more holistically recapitulate the situation described above. The cacophony of noise is getting ever louder, and meanwhile, our ability to filter this data to uncover the important signals hiding within has not improved at all.

We have developed technological tools that can filter the raw data and improve its informational extractability. However, these improvements are limited solely to endeavors that we are comfortable deferring to computers to manage for us. In all activities where humans still require involvement or apprehension, we are completely outmatched. On top of this, technology can be a tool, but it can also be a weapon. For every search, storage and AI tool that has helped to unbundle the noise into some semblance of a signal, there are other software tools that re-bundle the signal once again back into noise. Particularly social media, mainstream media, political propaganda and social science professions that overconfidently apply the newfound data abundance.

Taking all of these themes together, we have rampant technological shifts, overwhelming data propagation, and overconfident and confused human actors trying to adapt to these self-inflicted changes to achieve the unattainable: control. This means an increasing risk of the black swan events we so fiercely aim to circumvent. Less predictability, and more hubris as to our collective capacity to pattern-recognize and avoid those rare and historically pivotal events. This is a very dangerous cocktail.

An Homage To Endurance, Tenacity And Immutability

“I think much more likely is an even worse alternative: government will not cease inflating, but will, as it has been doing, try to suppress the open effects of this inflation. It will be driven by continual inflation into price controls, into increasing direction of the whole economic system. It is therefore now not merely a question of giving us better money, under which the market system will function infinitely better than it has ever done before… but of warding off the gradual decline into a totalitarian, planned system, which will, at least in this country, not come because anybody wants to introduce it, but will come step by step in an effort to suppress the effects of the inflation which is going on.” –Friedrich A. Hayek, “The Collective Works of F.A. Hayek,””Toward a Free Market Monetary System.”

Endurance, tenacity and immutability. While these attributes may sound too passive or unsubstantial to have value in our “move fast and break things” world, they are the exact traits required to survive the fragility of a system dashing feverishly towards instability.

Antifragility, an idea popularized in the 2012 book “Antifragile” by Nassim Taleb, describes systems or phenomena that gain strength from disorder. This book, part of a larger work focused on philosophical, statistical, and economic misconceptions relating to systemic risk, uncertainty, and randomness, has become part of the larger canon of Bitcoiner manifestos. This is despite Taleb’s recent baffling divorce from the community, which while a tad perplexing, should not detract from some of his work’s takeaways.

Bitcoiners have latched onto the themes of “Antifragile” as a framework to help elucidate some of Bitcoin’s game theory. How is it that there is no silver bullet that kills Bitcoin, there is no competitor that can magically overtake it, there is no government that can shut it down, and there is no central authority that can censor or confiscate it?

But the message does not stop there. Most important to the thesis of antifragility, each attack vector and shock to the system in fact causes Bitcoin to become stronger.

As Taleb writes:

“Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty. Yet, in spite of the ubiquity of the phenomenon, there is no word for the exact opposite of fragile. Let us call it antifragile. Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better. This property is behind everything that has changed with time: evolution, culture, ideas, revolutions, political systems, technological innovation, cultural and economic success, corporate survival, good recipes (say, chicken soup or steak tartare with a drop of cognac), the rise of cities, cultures, legal systems, equatorial forests, bacterial resistance … even our own existence as a species on this planet. And antifragility determines the boundary between what is living and organic (or complex), say, the human body, and what is inert, say, a physical object like the stapler on your desk… The antifragile loves randomness and uncertainty, which also means — crucially — a love of errors, a certain class of errors.”

We have seen firsthand how the market can reward an asset that exhibits antifragility. Astute macro investor Louis Gavkal has wisely observed that this is how the U.S. treasury market has evolved.

Today, investors have institutionalized portfolio management, packaged into strategies like 60/40 asset allocations (bonds/stocks), and slightly more volatility-adjusted strategies such as risk parity. However, this love affair with the treasury market as a diversification tool has not always been the case, especially from the perspective of global investors. In fact, treasuries may be losing this status. The godfather of risk parity, Ray Dalio himself, just recently confirmed the view that he would rather own bitcoin than bonds.

What has historically given treasuries their stature of primacy for so many years was the dollar’s reserve currency role. A feat attained through war, geopolitical victories, petrodollar arrangements, and the trade-offs of increasing consumerism and domestic debt accumulation in the U.S. to supply dollars abroad. All punctuated by a parallel hyper-financialization of our economy, with regulatory incentives to own treasuries and a global system addicted to dollar-based leverage and short of adequate collateral.

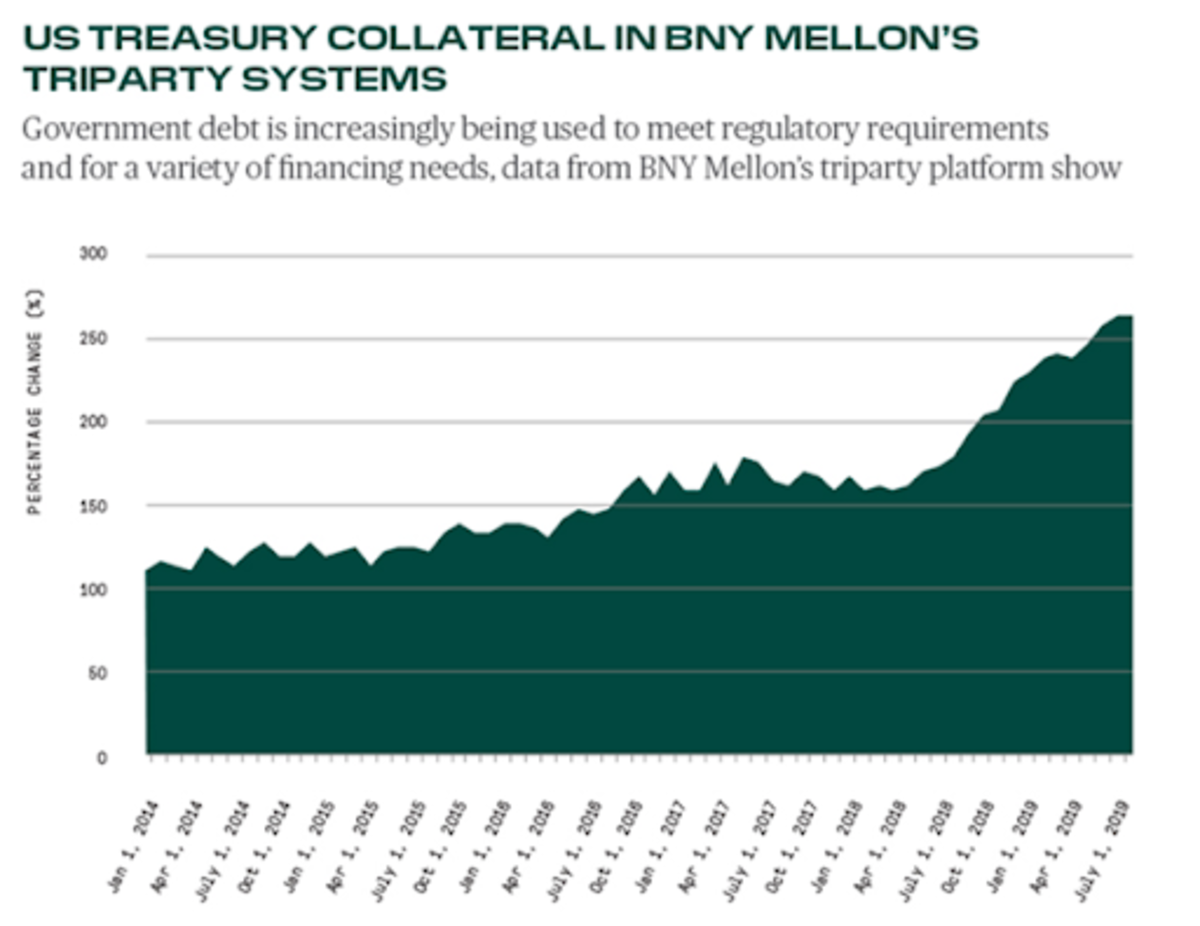

This collateral shortage has become particularly acute after quantitative easing has been significantly reducing the public supply of treasuries since 2009. All of these factors have helped create a treasury market monster with very resilient network effects for the U.S. dollar. Resilient to deleveraging elsewhere, resilient to market volatility, resilient to dollar shortages, and even resilient to cyclical inflation.

The treasury market is a massive battleship that has been chugging along full steam in one direction for many years. However, this ship is now altering its course. And this process is ever so slowly chipping away at those network effects. As the U.S. dollar necessarily loses some strength as a reserve money, the system will either need to deleverage or find a new source of collateral, a new antifragile asset.

Source: BNY Mellon

One way to think of the U.S. treasury market’s ability to maintain buyers and holders despite real interest rates, at least at negative 1% (depending on your gauge of inflation), is that this market has become a weigh station, a storage space for dollar-denominated assets, intended to balance existing portfolios of dollar-denominated equity, real estate and corporate debt holdings, as a reserve account that incentivizes participants to remain within the bounds of the existing USD ecosystem.

The Eurodollar system, U.S. dollars banked or held outside of the U.S. banking system, evolved to help accomplish this goal more efficiently at the global level.

The Eurodollar market size has exploded as the U.S. economy began to financialize in earnest: First in the early 1980s and then again in the 1990s and post-dot-com burst.

The start of this in the early 1980s coincided with the start of a 40-year bull market in U.S. treasuries:

Source: Federal Reserve Board

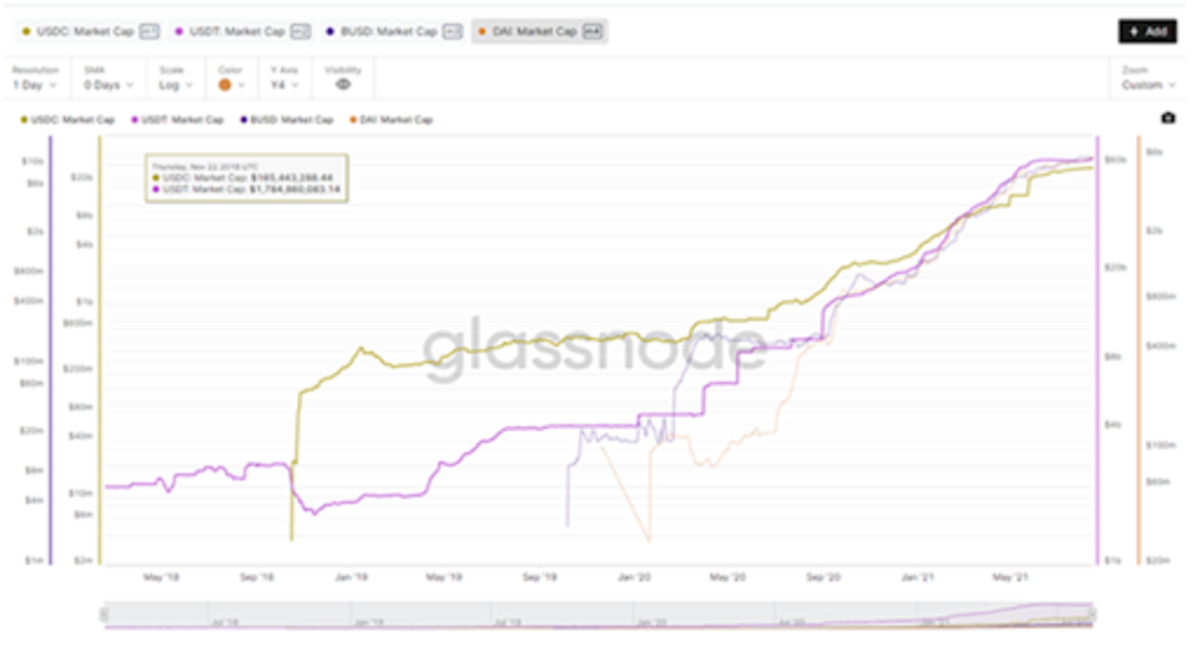

Such a concept of captively on-ramped capital is actually very similar to the stablecoin market in the Bitcoin and cryptocurrency ecosystems.

Source: @LudiMagistR; Glassnode

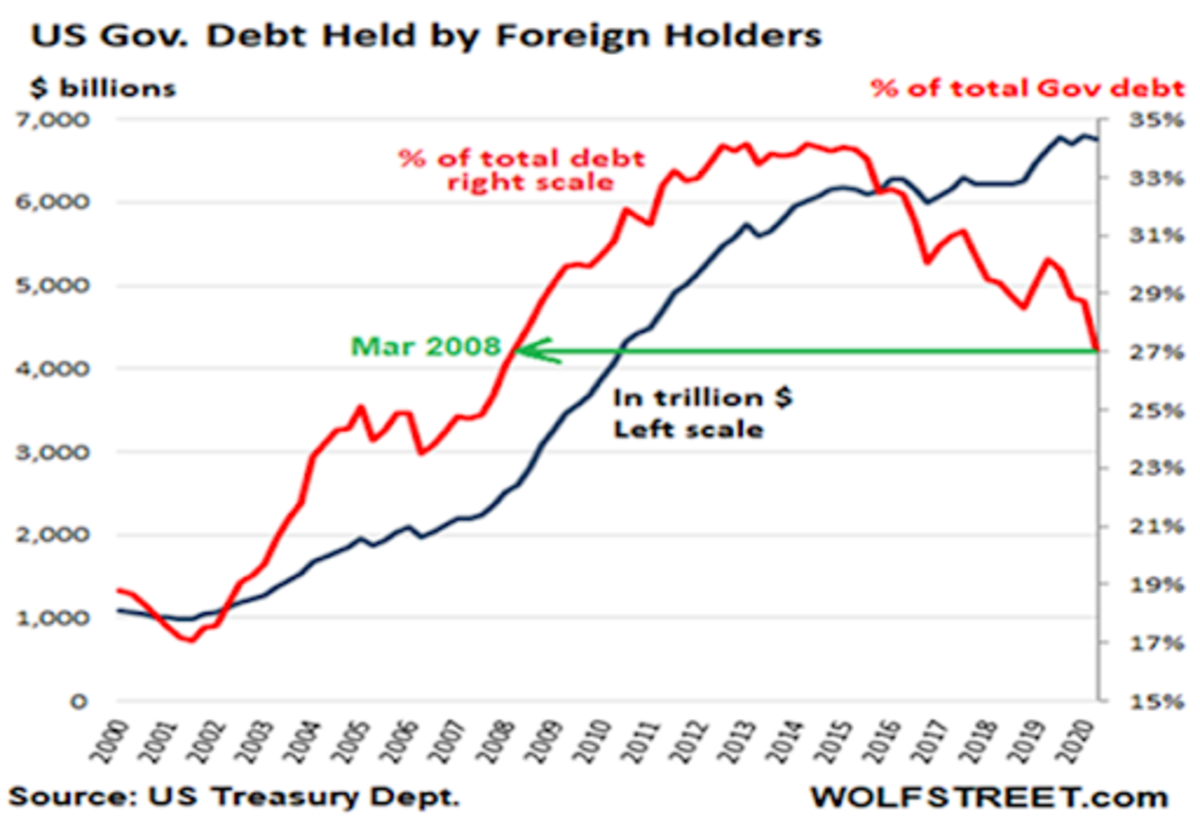

Unfortunately, for the U.S. dollar fiat ecosystem, there are signs of deterioration within its network effect. Foreign users are balking.

Source: Wolfstreet.com

A Poetic Phrase: Bitcoin Is A “Deep Structure”

“In a Paretian world, surface events can become a distraction, diverting attention from the deep structures molding these surface events. Surfaces are extraordinarily complex and rapidly evolving while the deep structures display more simplicity and stability. These deep structures are profoundly historical in nature — they evolve through positive feedback loops and path dependence. Snapshots become misleading and understanding requires a dynamic view of the landscape.” –John Hagel

We live in a world where things are intentionally made to fall apart. Quantity and popularity are valued above quality and depth. The news cycle is a meager 24 hours. Medical and health problems are addressed ex post facto with newly-invented medications and treatments, rather than by way of lifestyle changes and preventative measures.

Products are meant to become obsolete. Buildings are designed to last 20 years rather than 200. Tweets share ephemeral memes instead of lasting ideas, investments are made for instant return potential rather than lasting productive impact. And interest rates have collapsed to near zero, allowing us the mathematical permission to discount the future so that it is indistinguishable from the present.