Questo è un editoriale di opinione di Alex Gladstein, chief strategy officer della Human Rights Foundation e autore di”Check Your Financial Privilege”.

I. The Shrimp Fields

“Tutto è andato.”

–Kolyani Mondal

Cinquantadue anni fa, il ciclone Bhola uccise un stimato 1 milione di persone nella costa del Bangladesh. È, fino ad oggi, il ciclone tropicale più mortale mai registrato nella storia. Le autorità locali e internazionali conoscevano bene i rischi catastrofici di tali tempeste: negli anni’60, i funzionari regionali aveva costruito un’enorme serie di dighe per proteggere la costa e aprire più territorio all’agricoltura. Ma negli anni’80 dopo Dopo l’assassinio del leader dell’indipendenza Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, l’influenza straniera ha spinto un nuovo regime autocratico del Bangladesh a cambiare rotta. La preoccupazione per la vita umana è stata accantonata e la protezione del pubblico contro le tempeste è stata indebolita, tutto per aumentare le esportazioni per ripagare il debito.

Invece di rafforzare le foreste di mangrovie locali che proteggevano naturalmente il un terzo della popolazione che viveva vicino alla costa e invece di investire nella coltivazione di cibo per nutrire la nazione in rapida crescita, il governo ha preso prestiti dalla Banca Mondiale e Fondo monetario internazionale per espandere l’allevamento di gamberetti. Il processo di acquacoltura — controllato da una rete delle élite benestanti legate al regime, che consisteva nel spingere gli agricoltori a contrarre prestiti per”migliorare”le loro attività praticando buchi nelle dighe che proteggevano la loro terra dall’oceano, riempiendo i loro campi un tempo fertili di acqua salata. Quindi, lavoravano ore estenuanti per raccogliere a mano i giovani gamberetti dall’oceano, trascinarli nei loro stagni stagnanti e vendere quelli maturi ai signori locali dei gamberetti.

Con finanziamenti della Banca mondiale e del FMI, innumerevoli allevamenti e zone umide e foreste di mangrovie circostanti sono stati progettati in stagni di gamberetti noti come gher. Il delta del fiume Gange della zona è un luogo incredibilmente fertile, sede del Sundarbans, il più grande tratto di foresta di mangrovie. Ma poiché l’allevamento commerciale di gamberi è diventato la principale attività economica della regione, 45% delle mangrovie è stato tagliato via, lasciando milioni di persone esposte alle onde di 10 metri che possono infrangersi contro la costa durante principali cicloni. La terra arabile e la vita fluviale sono state lentamente distrutte dall’eccesso di salinità che fuoriesce dal mare. Intere foreste sono scomparse a causa dell’allevamento di gamberetti ha ucciso gran parte della vegetazione della zona,”trasformando questa terra un tempo generosa in un deserto acquoso”, secondo Coastal Development Partnership.

Una fattoria nella provincia di Khuna, allagata per produrre campi di gamberi

I signori dei gamberi, tuttavia, hanno fatto fortuna e i gamberi (noto come”oro bianco”) è diventato il seconda esportazione. A partire dal 2014, più di 1,2 milioni di bengalesi lavoravano nell’industria dei gamberetti, con 4,8 milioni di persone che ne dipendevano indirettamente, circa la metà dei poveri della costa. I raccoglitori di gamberetti, che svolgono il lavoro più duro, costituiscono il 50% della forza lavoro ma vedono solo 6% del profitto. Trenta per cento del si tratta di ragazze e ragazzi impegnati nel lavoro minorile, che lavorano fino a nove ore al giorno nell’acqua salata, per meno di $ 1 al giorno, con molti che abbandonano la scuola e rimangono analfabeti per farlo. Ci sono state proteste contro l’espansione dell’allevamento di gamberi, solo per essere represse violentemente. In un caso importante, una marcia è stata attaccata con esplosivi dai signori dei gamberi e dai loro teppisti, e una donna di nome Kuranamoyee Sardar è stata decapitato.

In un documento di ricerca del 2007, Sono stati esaminati 102 allevamenti di gamberetti del Bangladesh, rivelando che, su un costo di produzione di 1.084 dollari per ettaro, il reddito netto era di 689 dollari. I profitti delle esportazioni della nazione sono andati a scapito dei lavoratori dei gamberetti, i cui salari sono stati sgonfiati e il cui ambiente è stato distrutto.

In un rapporto della Environmental Justice Foundation, un allevatore costiero di nome Kolyani Mondal ha detto che”coltivava riso e allevava bestiame e pollame”, ma dopo che è stata imposta la raccolta dei gamberetti,”I suoi bovini e le sue capre hanno sviluppato una malattia simile alla diarrea e, insieme alle sue galline e anatre, sono tutti morti”.

Ora i suoi campi sono inondati di acqua salata, e ciò che rimane è poco produttivo: anni fa la sua famiglia poteva generare”18-19 mon di riso per ettaro”, ma ora ne può generare solo uno. Ricorda l’allevamento di gamberetti nella sua zona a partire dagli anni’80, quando agli abitanti del villaggio erano stati promessi più reddito e molto cibo e raccolti, ma ora”tutto è andato”. Gli allevatori di gamberetti che usano la sua terra le hanno promesso di pagarle 140 dollari all’anno, ma lei dice che il meglio che ottiene sono”rate occasionali di 8 dollari qua e là”. In passato, dice,”la famiglia riceveva la maggior parte delle cose di cui aveva bisogno dalla terra, ma ora non ci sono alternative se non andare al mercato a comprare cibo”.

In Bangladesh, miliardi di dollari dei prestiti di”aggiustamento strutturale”della Banca Mondiale e del FMI-così chiamati per il modo in cui costringono le nazioni mutuatarie a modificare le loro economie per favorire le esportazioni a scapito del consumo-hanno fatto crescere i profitti nazionali dei gamberetti da $ 2,9 milioni nel 1973 a $ 90 milioni nel 1986 a $590 milioni nel 2012. Come nella maggior parte dei casi con lo sviluppo paesi, le entrate sono state utilizzate per onorare il debito estero, sviluppare risorse militari e riempire le tasche dei funzionari governativi. Quanto ai servi dei gamberi, sono stati impoveriti: meno liberi, più dipendenti e meno capaci di nutrirsi di prima. A peggiorare le cose, gli studi mostrano che“i villaggi sono protetti dalla tempesta dalle foreste di mangrovie subiscono un numero significativamente inferiore di morti”rispetto ai villaggi a cui sono state rimosse o danneggiate le loro protezioni.

Sotto la pressione dell’opinione pubblica, nel 2013 la Banca Mondiale ha prestato al Bangladesh $ 400 milioni per tentare di invertire la rotta il danno ecologico. In altre parole, la Banca Mondiale riceverà un compenso sotto forma di interessi per cercare di risolvere il problema che ha creato in primo luogo. Nel frattempo, la Banca mondiale ha prestato miliardi a paesi di tutto il mondo da Ecuador a Marocco al India per sostituire l’agricoltura tradizionale con la produzione di gamberetti.

La sostiene che il Bangladesh è”una storia straordinaria di riduzione della povertà e sviluppo”. Sulla carta, la vittoria è dichiarata: paesi come il Bangladesh tendono a mostrare una crescita economica nel tempo man mano che le loro esportazioni aumentano per soddisfare le loro importazioni. Ma i proventi delle esportazioni vanno principalmente all’élite dominante e ai creditori internazionali. Dopo 10 aggiustamenti strutturali, il debito del Bangladesh è cresciuto in modo esponenziale dai $ 145 milioni nel 1972 al massimo storico di 95,9 miliardi di dollari nel 2022. Il paese sta attualmente affrontando un’altra crisi della bilancia dei pagamenti e proprio questo mese ha accettato di ottenere il suo 11° prestito dal FMI, questa volta un $4,5 miliardi salvataggio, in cambio di ulteriori aggiustamenti. La Banca e il Fondo affermano di voler aiutare i paesi poveri, ma il risultato evidente dopo oltre 50 anni di politiche è che nazioni come il Bangladesh sono più dipendenti e indebitate che mai.

Durante gli anni’90 in Sulla scia della crisi del debito del terzo mondo, c’è stata un’ondata di controllo pubblico globale sulla Banca e sul Fondo: studi critici, proteste di piazza e una diffusa convinzione bipartisan (anche nel sale del Congresso degli Stati Uniti) che queste istituzioni andavano da dispendiose a distruttive. Ma questo sentimento e attenzione sono in gran parte svaniti. Oggi la Banca e il Fondo riescono a mantenere un basso profilo sulla stampa. Quando emergono, tendono a essere liquidate come sempre più irrilevanti, accettate come problematiche ma necessarie o addirittura accolte come utili.

La realtà è che queste organizzazioni hanno impoverito e messo in pericolo milioni di persone; dittatori e cleptocrati arricchiti; e mettere da parte i diritti umani per generare un flusso multimiliardario di cibo, risorse naturali e manodopera a basso costo dai paesi poveri a quelli ricchi. Il loro comportamento in paesi come il Bangladesh non è un errore o un’eccezione: è il loro modo preferito di fare affari.

II. Inside The World Bank And FMI

“Ricordiamoci che lo scopo principale degli aiuti non è aiutare altre nazioni ma aiutare noi stessi.”

Il FMI è il prestatore internazionale di ultima istanza al mondo e la Banca mondiale è il la banca di sviluppo più grande del mondo. Il loro lavoro viene svolto per conto dei loro principali creditori, che storicamente sono stati Stati Uniti, Regno Unito, Francia, Germania e Giappone.

FMI e Mondo Uffici della banca a Washington, DC

Le organizzazioni gemelle — fisicamente riunite nella loro sede centrale a Washington, DC — sono stati creati alla Conferenza di Bretton Woods nel New Hampshire nel 1944 come due pilastri del nuovo ordine monetario globale guidato dagli Stati Uniti. Per tradizione, la Banca mondiale è guidata da un americano e il FMI da un europeo.

Il loro scopo iniziale era quello di aiutare a ricostruire l’Europa e il Giappone dilaniati dalla guerra, con la Banca che si concentrava su prestiti specifici per lo sviluppo progetti e il Fondo per affrontare i problemi della bilancia dei pagamenti tramite”salvataggi”per mantenere il flusso degli scambi anche se i paesi non potrebbero permettersi ulteriori importazioni.

Le nazioni devono aderire al FMI per ottenere l’accesso ai “vantaggi” della Banca Mondiale. Oggi ci sono 190 stati membri: ognuno ha depositato un mix della propria valuta più”moneta più forte”(in genere dollari, valute europee o oro) quando hanno aderito, creando un pool di riserve.

Quando i membri incontrano problemi cronici di bilancia dei pagamenti e non possono concedere prestiti rimborsi, il Fondo offre loro credito dal pool a multipli variabili di quanto inizialmente depositato, a condizioni sempre più costose.

Il Fondo è tecnicamente una banca centrale sovranazionale, poiché dal 1969 ha coniato la propria valuta: i diritti speciali di prelievo (SDR), il cui valore si basa su un paniere delle principali valute mondiali. Oggi, l’SDR è coperto dal 45% di dollari, il 29% euro, 12% yuan, 7% yen e 7% sterline. La capacità di prestito totale della FMI ammonta oggi a 1 trilione di dollari.

Tra il 1960 e il 2008, il Fondo si è concentrato principalmente sull’assistenza ai paesi in via di sviluppo con-prestiti a tasso d’interesse. Poiché le valute emesse dai paesi in via di sviluppo non sono liberamente convertibili, di solito non possono essere convertite in beni o servizi all’estero. Gli stati in via di sviluppo devono invece guadagnare valuta forte attraverso le esportazioni. A differenza degli Stati Uniti, che possono semplicemente emettere la valuta di riserva globale, paesi come lo Sri Lanka e il Mozambico spesso finiscono i soldi. A quel punto, la maggior parte dei governi, specialmente quelli autoritari, preferisce la soluzione rapida di prendere in prestito dal Fondo per il futuro del proprio paese.

Per quanto riguarda la Banca, afferma che il suo compito è fornire credito ai paesi in via di sviluppo per”ridurre la povertà, aumentare prosperità condivisa e promuovere lo sviluppo sostenibile”. La Banca stessa è suddivisa in cinque parti, che vanno dalla Banca Internazionale per la Ricostruzione e lo Sviluppo (IBRD), che si concentra su prestiti”duri”più tradizionali ai paesi in via di sviluppo più grandi (si pensi al Brasile o all’India) all’Associazione Internazionale per lo Sviluppo (IDA ), che si concentra su prestiti senza interessi “agevolati” con lunghi periodi di grazia per i paesi più poveri. L’IBRD fa soldi in parte attraverso l’effetto Cantillon: prendendo in prestito a condizioni favorevoli dai suoi creditori e partecipanti al mercato privato che hanno un accesso più diretto a capitali più economici e poi prestando quei fondi a condizioni più elevate ai paesi poveri che non hanno tale accesso.

I prestiti della Banca Mondiale sono tradizionalmente specifici per progetti o settori e si sono concentrati sulla facilitazione dell’esportazione di merci grezze (ad esempio: finanziamento di strade, tunnel, dighe e porti necessari per estrarre minerali dal terreno e nei mercati internazionali) e sulla trasformazione dell’agricoltura di consumo tradizionale in agricoltura industriale o acquacoltura in modo che i paesi possano esportare più cibo e beni in Occidente.

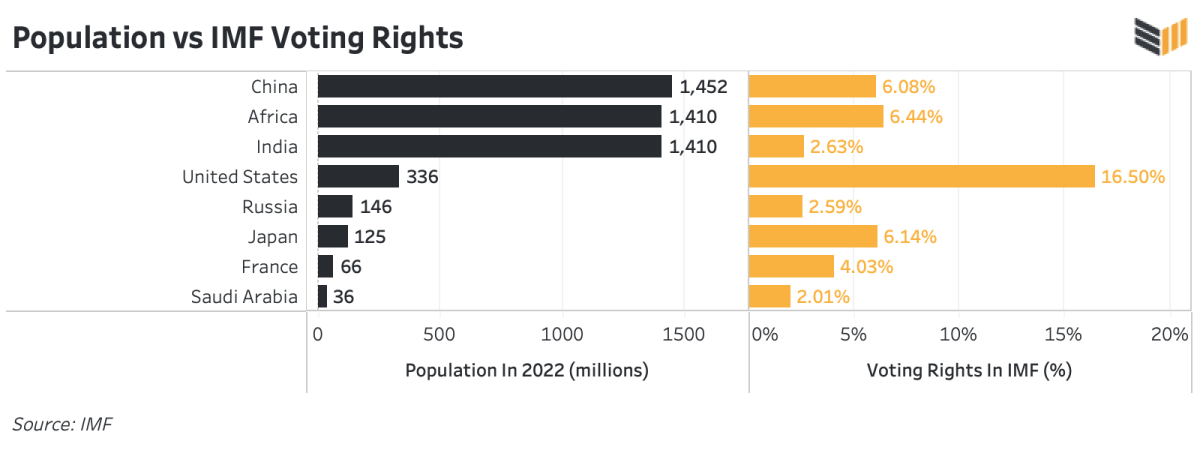

Gli Stati membri della Banca e del Fondo non hanno potere di voto basato sulla loro popolazione. Piuttosto, l’influenza è stata creata sette decenni fa per favorire gli Stati Uniti, l’Europa e il Giappone rispetto al resto del mondo. Tale predominio si è indebolito solo leggermente negli ultimi anni.

Oggi gli Stati Uniti detengono ancora di gran lunga la quota di voti più ampia, con il 15,6% del Banca e il 16,5% della Fondo, sufficiente per porre il veto da solo a qualsiasi decisione importante, che richiede l’85% dei voti in entrambe le istituzioni. Il Giappone detiene il 7,35% dei voti della Banca e il 6,14% del Fondo; Germania 4,21% e 5,31%; Francia e Regno Unito 3,87% e 4,03% ciascuno; e l’Italia il 2,49% e il 3,02%.

L’India invece con i suoi 1,4 miliardi di abitanti ha solo il 3,04% dei voti alla Banca e appena il 2,63% al Fondo: meno potere del suo ex padrone coloniale pur avendo un popolazione 20 volte più grande. Gli 1,4 miliardi di cinesi ottengono il 5,7% dalla Banca e il 6,08% dal fondo, più o meno la stessa quota dei Paesi Bassi più Canada e Australia. Il Brasile e la Nigeria, i paesi più grandi dell’America Latina e dell’Africa, hanno all’incirca la stessa influenza dell’Italia, un’ex potenza imperiale in pieno declino.

La minuscola Svizzera con appena 8,6 milioni di abitanti ha l’1,47% dei voti alla Banca Mondiale e l’1,17% dei voti al FMI: all’incirca la stessa quota di Pakistan, Indonesia, Bangladesh ed Etiopia messi insieme, nonostante abbiano 90 volte meno persone.

Popolazione contro diritti di voto del FMI

Queste quote di voto dovrebbero approssimare la quota di ogni paese dell’economia mondiale, ma la loro struttura dell’era imperiale aiuta a colorare il modo in cui vengono prese le decisioni. Sessantacinque anni dopo la decolonizzazione, le potenze industriali guidate dagli Stati Uniti continuano ad avere il controllo più o meno totale sul commercio globale e sui prestiti, mentre i paesi più poveri in effetti non hanno voce in capitolo.

Il G-5 (Stati Uniti, Giappone, Germania, Regno Unito e Francia) dominano il consiglio esecutivo del FMI, anche se costituiscono una percentuale relativamente piccola della popolazione mondiale. Il G-10 più l’Irlanda, l’Australia e la Corea costituiscono oltre il 50% dei voti, il che significa che con un po’di pressione sui propri alleati, gli Stati Uniti possono prendere decisioni anche su specifiche decisioni di prestito, che richiedono la maggioranza.

Per integrare il potere di prestito trilione di dollari dell’FMI , il gruppo della Banca Mondiale rivendica più di 350 miliardi di dollari in prestiti in essere in più di 150 paesi. Questo credito è aumentato negli ultimi due anni, poiché le organizzazioni sorelle hanno ha prestato centinaia di miliardi di dollari ai governi che hanno bloccato le loro economie in risposta alla pandemia di COVID-19.

Negli ultimi mesi, Banca e Fondo ha iniziato a orchestrare accordi da miliardi di dollari per”salvare”i governi minacciati dagli aggressivi aumenti dei tassi di interesse della Federal Reserve statunitense. Questi clienti sono spesso violatori dei diritti umani che prendono in prestito senza permesso dai loro cittadini, che alla fine saranno i responsabili del rimborso del capitale più gli interessi sui prestiti. Il FMI sta attualmente salvando il dittatore egiziano Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, responsabile della più grande massacro di manifestanti da piazza Tiananmen — ad esempio, con $ 3 miliardi. Nel frattempo, la Banca mondiale, durante lo scorso anno, ha erogato un prestito di $ 300 milioni a un governo etiope che stava commettendo genocidio nel Tigray.

L’effetto cumulativo delle politiche della Banca e del Fondo è molto maggiore dell’importo cartaceo dei loro prestiti, poiché i loro prestiti guidano l’assistenza bilaterale. Si stima che”ogni dollaro fornito al Terzo Mondo dal FMI sblocchi altri 4-7 dollari di nuovi prestiti e rifinanziamenti da banche commerciali e governi dei paesi ricchi”. Allo stesso modo, se la Banca e il Fondo si rifiutano di concedere prestiti a un determinato paese, il resto del mondo in genere segue l’esempio.

È difficile sopravvalutare il vasto impatto che la Banca e il Fondo hanno avuto nelle nazioni in via di sviluppo, specialmente nei decenni formativi dopo la seconda guerra mondiale. Entro il 1990 e la fine della Guerra Fredda, il FMI aveva concesso crediti a 41 paesi in Africa, 28 paesi in America Latina, 20 paesi in Asia, otto paesi in Medio Oriente e cinque paesi in Europa, colpendo 3 miliardi di persone, o quelli che allora erano i due terzi della popolazione mondiale. La Banca mondiale ha concesso prestiti a più di 160 Paesi. Rimangono le istituzioni finanziarie internazionali più importanti del pianeta.

III. Adeguamento strutturale

“L’adeguamento è un compito sempre nuovo e senza fine”

–Otmar Emminger, ex direttore del FMI e creatore di SDR

Oggi, i titoli finanziari sono pieni di storie sulle visite del FMI in paesi come lo Sri Lanka e Ghana. Il risultato è che il Fondo presta miliardi di dollari ai paesi in crisi in cambio di ciò che è noto come aggiustamento strutturale.

In un prestito di aggiustamento strutturale, i mutuatari non devono solo rimborsare il capitale più gli interessi: devono devono anche accettare di cambiare le loro economie in base alle richieste di banche e fondi. Questi requisiti stabiliscono quasi sempre che i clienti massimizzino le esportazioni a scapito del consumo interno.

Durante la ricerca per questo saggio, l’autore ha imparato molto dal lavoro della studiosa di sviluppo Cheryl Payer, che ha scritto libri e articoli fondamentali su l’influenza della Banca e del Fondo negli anni’70,’80 e’90. Questa autrice potrebbe non essere d’accordo con le”soluzioni”di Payer, che, come quelle della maggior parte dei critici della Banca e del Fondo, tendono ad essere socialiste, ma molte delle sue osservazioni sull’economia globale sono vere indipendentemente dall’ideologia.

“È un obiettivo esplicito e fondamentale dei programmi del FMI”, ha scritto,”scoraggiare il consumo locale per liberare risorse per l’esportazione”.

Questo punto non sarà mai sottolineato abbastanza.

La versione ufficiale è che la Banca e il Fondo sono stati progettati per “promuovere una crescita economica sostenibile, promuovere standard di vita più elevati e ridurre la povertà”. Ma le strade e le dighe che la Banca costruisce non sono progettate per aiutare a migliorare i trasporti e l’elettricità per la gente del posto, ma piuttosto per rendere facile per le multinazionali estrarre ricchezza. E i salvataggi forniti dall’FMI non sono per”salvare”un paese dalla bancarotta-che probabilmente sarebbe la cosa migliore per esso in molti casi-ma piuttosto per consentirgli di pagare il suo debito con ancora più debito, in modo che il prestito originario non si trasformi in un buco nel bilancio di una banca occidentale.

Nei suoi libri su Bank and Fund, Payer descrive come le istituzioni affermano che la loro condizionalità sui prestiti consente ai paesi mutuatari di”raggiungere un più sano equilibrio di commercio e pagamenti”. Ma il vero scopo, dice, è”corrompere i governi per impedire loro di apportare i cambiamenti economici che li renderebbero più indipendenti e autosufficienti”. Quando i paesi rimborsano i loro prestiti di aggiustamento strutturale, viene data priorità al servizio del debito e la spesa interna deve essere”adeguata”al ribasso.

I prestiti del FMI venivano spesso assegnati attraverso un meccanismo chiamato”accordo stand-by”, un linea di credito che ha rilasciato fondi solo quando il governo mutuatario ha affermato di raggiungere determinati obiettivi. Da Jakarta a Lagos a Buenos Aires, il personale del FMI arrivava in volo (sempre in prima o in business class) per incontrare i governanti non democratici e offrire loro milioni o miliardi di dollari in cambio del rispetto del loro manuale economico.

Richieste tipiche del FMI. includerebbe:

Svalutazione della valuta Abolizione o riduzione dei controlli sui cambi e sulle importazioni Restrizione del credito bancario interno Tassi di interesse più elevati Aumento delle tasse Fine dei sussidi al consumo su cibo ed energia Limiti salariali Restrizioni alla spesa pubblica, in particolare nel settore sanitario e dell’istruzione Condizioni legali favorevoli e incentivi per le multinazionali Svendita imprese statali e rivendicazioni sulle risorse naturali a prezzi di svendita

Anche la Banca mondiale aveva il suo playbook. Il pagatore fornisce esempi:

L’apertura di regioni precedentemente remote attraverso investimenti nei trasporti e nelle telecomunicazioniAiutare le multinazionali nel settore minerarioInsistere sulla produzione per l’esportazionePremere i mutuatari per migliorare i privilegi legali per le passività fiscali degli investimenti stranieriOpporsi alle leggi sul salario minimo e all’attività sindacaleMettere le protezioni per le imprese di proprietà localeFinanziamento di progetti che si appropriano di terra, acqua e foreste dai poveri e li consegnano alle multinazionaliRiduzione della produzione manifatturiera e alimentare a scapito dell’esportazione di risorse naturali e materie prime

I governi del Terzo Mondo sono stati storicamente costretti ad accettare a una combinazione di queste politiche, a volte note come “Washington Consensus”, al fine di attivare il rilascio continuo di prestiti bancari e fondi.

Le ex potenze coloniali tendono a concentrare i loro prestiti di”sviluppo”su ex colonie o aree di influenza: Francia in Africa occidentale, Giappone in Indonesia, Gran Bretagna in Africa orientale e Asia meridionale e Stati Uniti in America Latina. Un esempio notevole è la zona CFA, dove 180 milioni di persone in 15 paesi africani sono ancora costretti a utilizzare una valuta coloniale francese. Su suggerimento del FMI, nel 1994 la Francia ha svalutato il CFA del 50%, devastanti i risparmi e il potere d’acquisto di decine di milioni di persone che vivono in paesi che vanno dal Senegal alla Costa d’Avorio al Gabon, tutto per esportare materie prime più competitivo.

Il risultato di Bank and Le politiche dei fondi sul Terzo mondo sono state notevolmente simili a quelle vissute sotto l’imperialismo tradizionale: deflazione salariale, perdita di autonomia e dipendenza agricola. La grande differenza è che nel nuovo sistema, la spada e la pistola sono state sostituite dal debito armato.

Negli ultimi 30 anni, l’aggiustamento strutturale si è intensificato per quanto riguarda il numero medio di condizioni nei prestiti concessi dalla Banca e dal Fondo. Prima del 1980, la Banca generalmente non concedeva prestiti di adeguamento strutturale, quasi tutto era specifico per progetto o settore. Ma da allora, i prestiti di salvataggio”spendi come vuoi”con contropartite economiche sono diventati una parte crescente della politica della banca. Per il FMI, sono la sua linfa vitale.

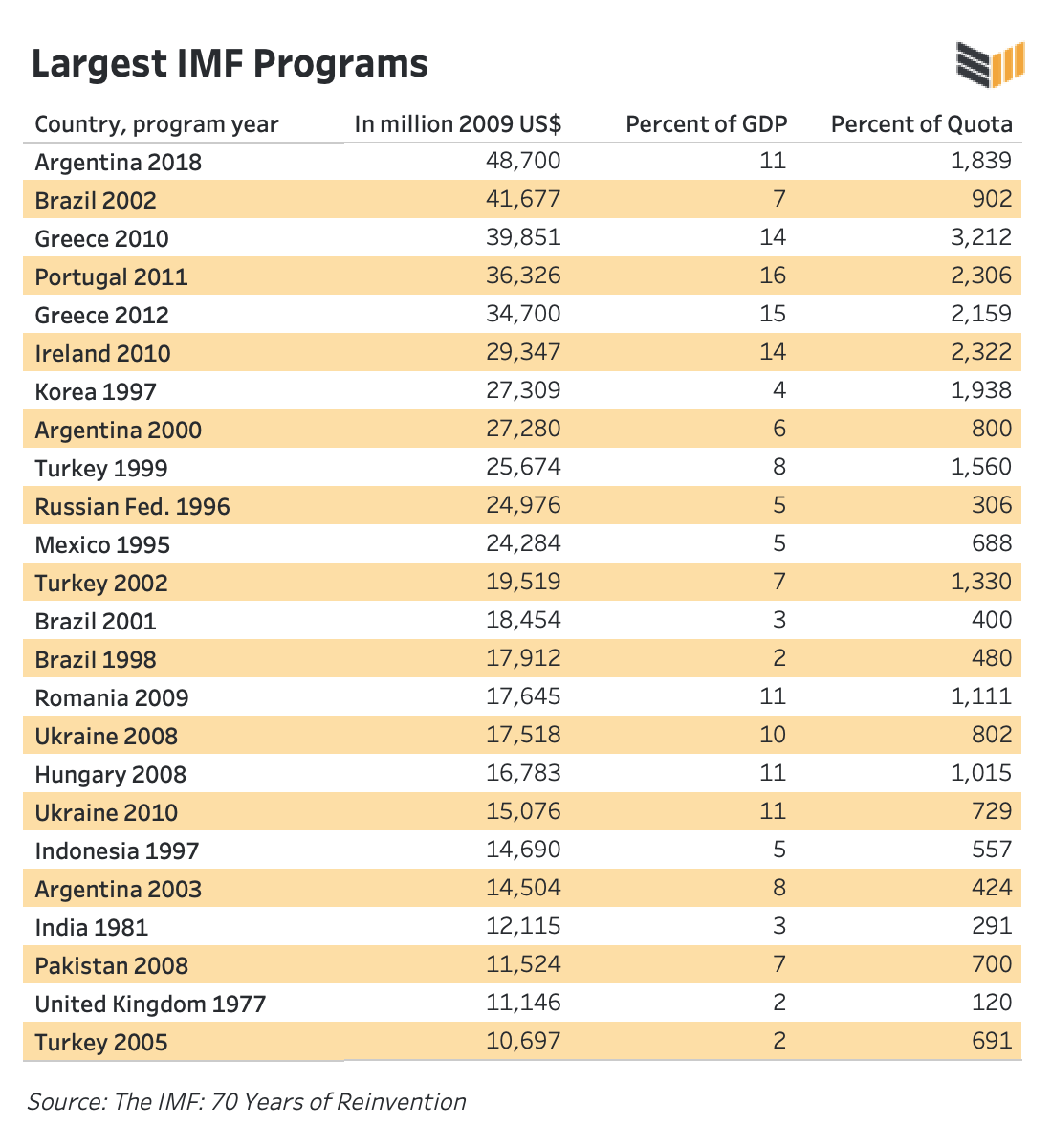

Ad esempio, quando il FMI ha salvato la Corea del Sud e l’Indonesia con pacchetti da 57 miliardi di dollari e 43 miliardi di dollari durante la crisi finanziaria asiatica del 1997, ha imposto pesanti condizioni. I mutuatari dovevano firmare accordi che”assomigliavano più ad alberi di Natale che a contratti, con da 50 a 80 condizioni dettagliate che coprivano tutto, dalla deregolamentazione dei monopoli dell’aglio alle tasse sui mangimi per il bestiame e alle nuove leggi ambientali”, secondo il politologo Mark S. Copelvitch.

Un analisi ha mostrato che il FMI aveva allegato, in media, 20 condizioni a ciascun prestito concesso nei due anni precedenti, un aumento storico. Paesi come Giamaica, Grecia e Cipro hanno preso in prestito negli ultimi anni con una media di 35 condizioni ciascuno. Vale la pena notare che le condizioni della Banca e del Fondo non hanno mai incluso protezioni sulla libertà di parola o sui diritti umani, o restrizioni sulle spese militari o sulla violenza della polizia.

Un’ulteriore svolta della politica della Banca e del Fondo è quella che è nota come “doppio prestito”: il denaro viene prestato per costruire, ad esempio, una diga idroelettrica, ma la maggior parte se non tutto il denaro viene versato alle compagnie occidentali. Quindi, il contribuente del Terzo Mondo è gravato di capitale e interessi, e il Nord viene rimborsato il doppio.

Il contesto del doppio prestito è che gli stati dominanti estendono il credito attraverso la Banca e il Fondo alle ex colonie, dove i governanti locali spesso spendono il nuovo denaro direttamente a società multinazionali che traggono profitto da servizi di consulenza, costruzione o importazione. La conseguente e richiesta svalutazione della valuta, i controlli sui salari e la stretta del credito bancario imposti dall’adeguamento strutturale della Banca e del Fondo svantaggiano gli imprenditori locali che sono bloccati in un sistema fiat al collasso e isolato e avvantaggiano le multinazionali native del dollaro, dell’euro o dello yen.

Un’altra fonte chiave per questo autore è stata il magistrale libro”The Lords of Poverty”dello storico Graham Hancock, scritto per riflettere sui primi cinquant’anni di politica delle banche e dei fondi e sull’assistenza estera in generale.

“La Banca Mondiale”, scrive Hancock,”è la prima ad ammettere che su ogni $ 10 che riceve, circa $ 7 vengono effettivamente spesi in beni e servizi dai ricchi paesi industrializzati.”

p>

Negli anni’80, quando i finanziamenti bancari si stavano espandendo rapidamente in tutto il mondo, ha osservato che”per ogni dollaro di tasse statunitensi contribuito, 82 centesimi vengono immediatamente restituiti alle imprese americane sotto forma di ordini di acquisto”. Questa dinamica vale non solo per i prestiti ma anche per gli aiuti. Ad esempio, quando gli Stati Uniti o la Germania inviano un aereo di soccorso in un paese in crisi, i costi di trasporto, cibo, medicine e stipendi del personale vengono aggiunti a ciò che è noto come ODA, o”assistenza ufficiale allo sviluppo”. Sui libri, sembra aiuto e assistenza. Ma la maggior parte del denaro viene restituita direttamente alle società occidentali e non viene investita localmente.

Riflettendo sulla crisi del debito del terzo mondo degli anni’80, Hancock ha osservato che”70 centesimi su ogni dollaro di assistenza americana non lasciato gli Stati Uniti”. Il Regno Unito, da parte sua, ha speso un enorme 80% dei suoi aiuti durante quel periodo direttamente in beni e servizi britannici.

“Un anno”, scrive Hancock, “i contribuenti britannici hanno fornito alle agenzie umanitarie multilaterali 495 milioni di sterline; nello stesso anno, però, le ditte britanniche hanno ricevuto contratti per un valore di 616 milioni di sterline”. Hancock ha affermato che si potrebbe”fare affidamento sulle agenzie multilaterali per l’acquisto di beni e servizi britannici per un valore equivalente al 120% del contributo multilaterale totale della Gran Bretagna”. pensare che sia caritatevole è esattamente l’opposto.

E come sottolinea Hancock, i budget per gli aiuti esteri aumentano sempre, indipendentemente dal risultato. Proprio come il progresso è la prova che l’aiuto sta funzionando, una”mancanza di progresso è la prova che il dosaggio è stato insufficiente e deve essere aumentato”.

Alcuni sostenitori dello sviluppo, scrive,”sostengono che sarebbe inopportuno negare l’aiuto ai veloci (quelli che avanzano); altri, che sarebbe crudele negarlo ai bisognosi (coloro che ristagnano). L’aiuto è quindi come lo champagne: nel successo te lo meriti, nel fallimento ne hai bisogno.”

IV. La trappola del debito

“Il concetto di Terzo Mondo o Sud e la politica degli aiuti ufficiali sono inscindibili. Sono due facce della stessa medaglia. Il Terzo Mondo è la creazione degli aiuti esteri: senza aiuti esteri non c’è Terzo Mondo”.

Secondo la Banca Mondiale, il suo obiettivo è”aiutare la rai se gli standard di vita nei paesi in via di sviluppo incanalando le risorse finanziarie dai paesi sviluppati al mondo in via di sviluppo.”

Ma se la realtà fosse l’opposto?

All’inizio, a partire dagli anni’60, c’è stato un enorme flusso di risorse dai paesi ricchi a quelli poveri. Questo è stato apparentemente fatto per aiutarli a svilupparsi. Payer scrive che è stato a lungo considerato”naturale”che il capitale”fluisse in una sola direzione dalle economie industriali sviluppate al Terzo Mondo”.

Il ciclo di vita di un prestito della Banca Mondiale: positivo, poi profondamente flussi di cassa negativi per il paese del mutuatario

Ma, come ci ricorda,”a un certo punto il mutuatario deve pagare al suo creditore più di quanto ha ricevuto dal creditore e per tutta la durata del prestare questo eccesso è molto più alto dell’importo originariamente preso in prestito.”

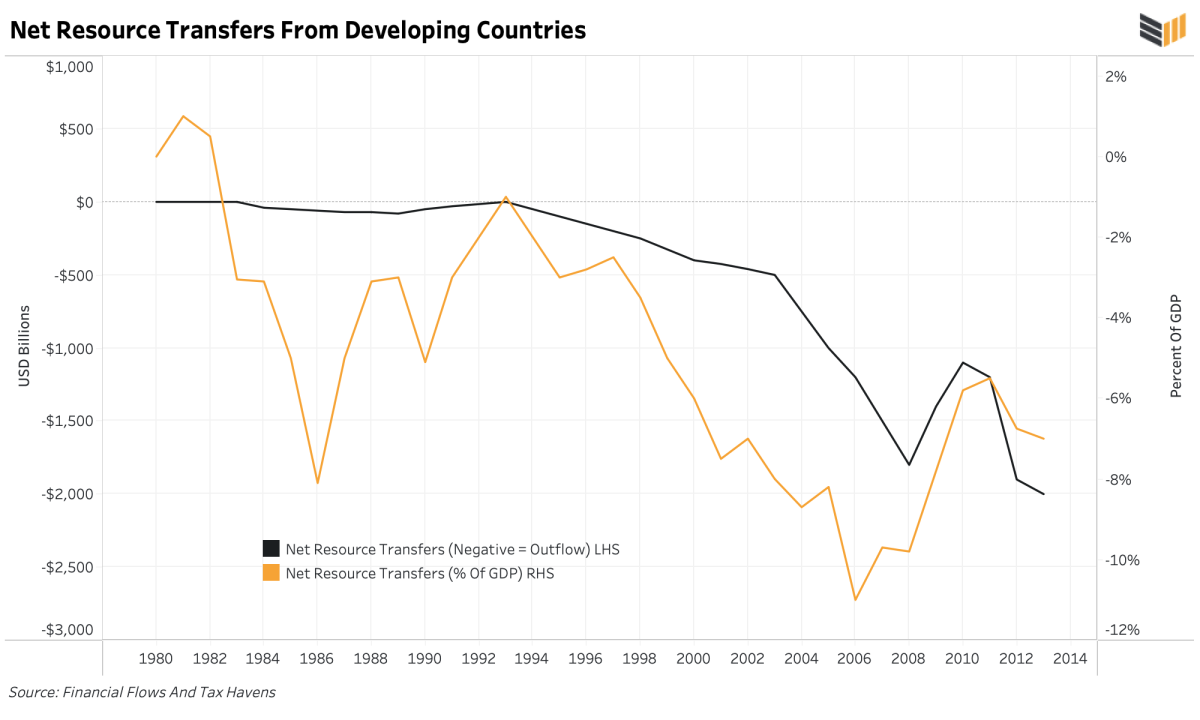

Nell’economia globale, questo punto si è verificato nel 1982, quando il flusso di risorse si è definitivamente invertito. Da allora, c’è stato un flusso netto annuale di fondi dai paesi poveri a quelli ricchi. Questo è iniziato con una media di 30 miliardi di dollari all’anno che scorrevano dal sud al nord tra la metà e la fine degli anni’80, ed è oggi nell’ordine di trilioni di dollari all’anno. Tra il 1970 e il 2007 — dalla fine del gold standard alla Grande Crisi Finanziaria — il servizio del debito totale pagato dai paesi poveri a quelli ricchi è stato di 7,15 trilioni di dollari.

Trasferimenti netti di risorse dai paesi in via di sviluppo: sempre più negativi dal 1982

Per fare un esempio di come potrebbe essere in un dato anno, nel 2012 i paesi in via di sviluppo hanno ricevuto $1,3 trilioni, compresi tutti i redditi, gli aiuti e gli investimenti. Ma nello stesso anno sono usciti più di 3,3 trilioni di dollari. In altre parole, secondo l’antropologo Jason Hickel,”i paesi in via di sviluppo hanno inviato al resto del mondo 2 trilioni di dollari in più rispetto a quelli che hanno ricevuto”.

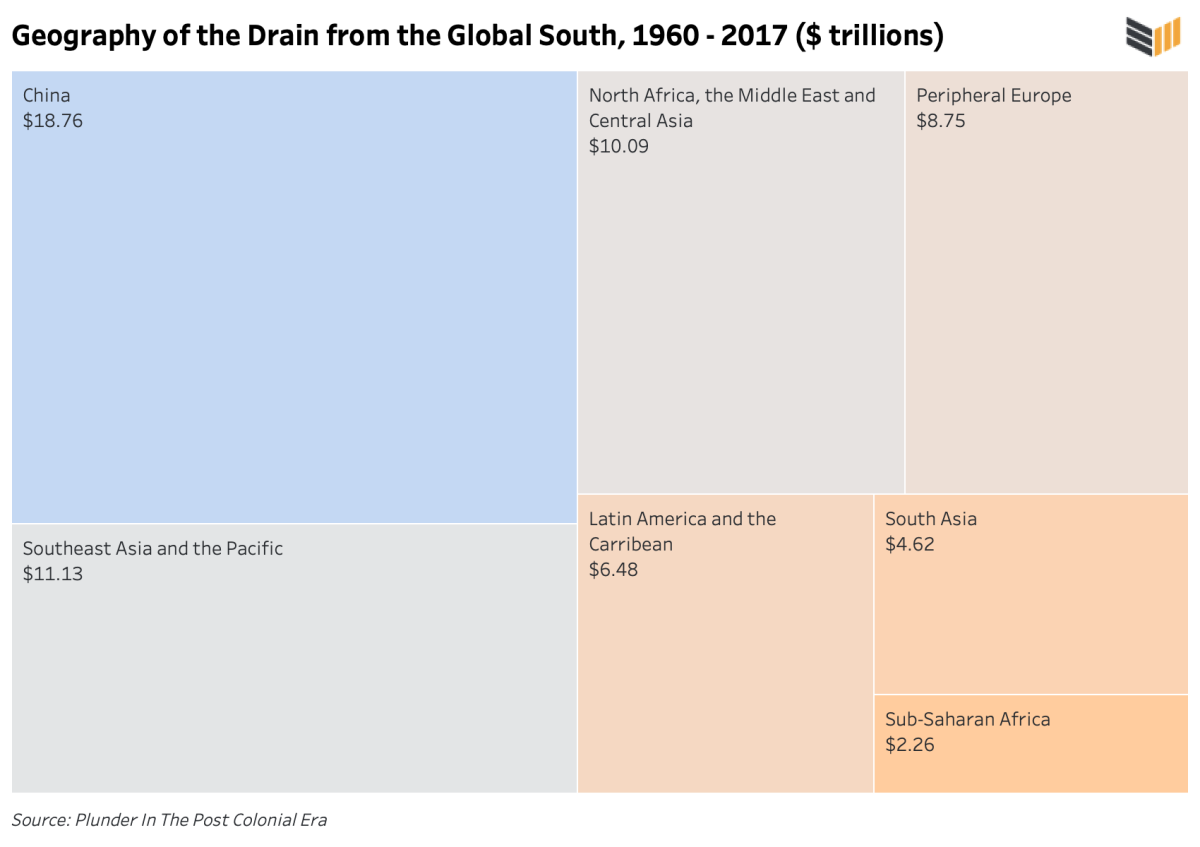

Quando tutti i flussi sono stati sommati dal 1960 al 2017, è emersa una triste verità: 62 trilioni di dollari sono stati sottratti al mondo in via di sviluppo, l’equivalente di 620 piani Marshall in dollari di oggi.

Il FMI e la Banca mondiale avrebbero dovuto risolvere i problemi della bilancia dei pagamenti, e aiutare i paesi poveri a diventare più forti e più sostenibili. L’evidenza è stata l’esatto opposto.

“Per ogni dollaro di aiuti che i paesi in via di sviluppo ricevono”, scrive Hickel,”perdono 24 dollari in deflussi netti”. Invece di porre fine allo sfruttamento e allo scambio iniquo, gli studi mostrano che le politiche di aggiustamento strutturale sono cresciute loro in modo massiccio.

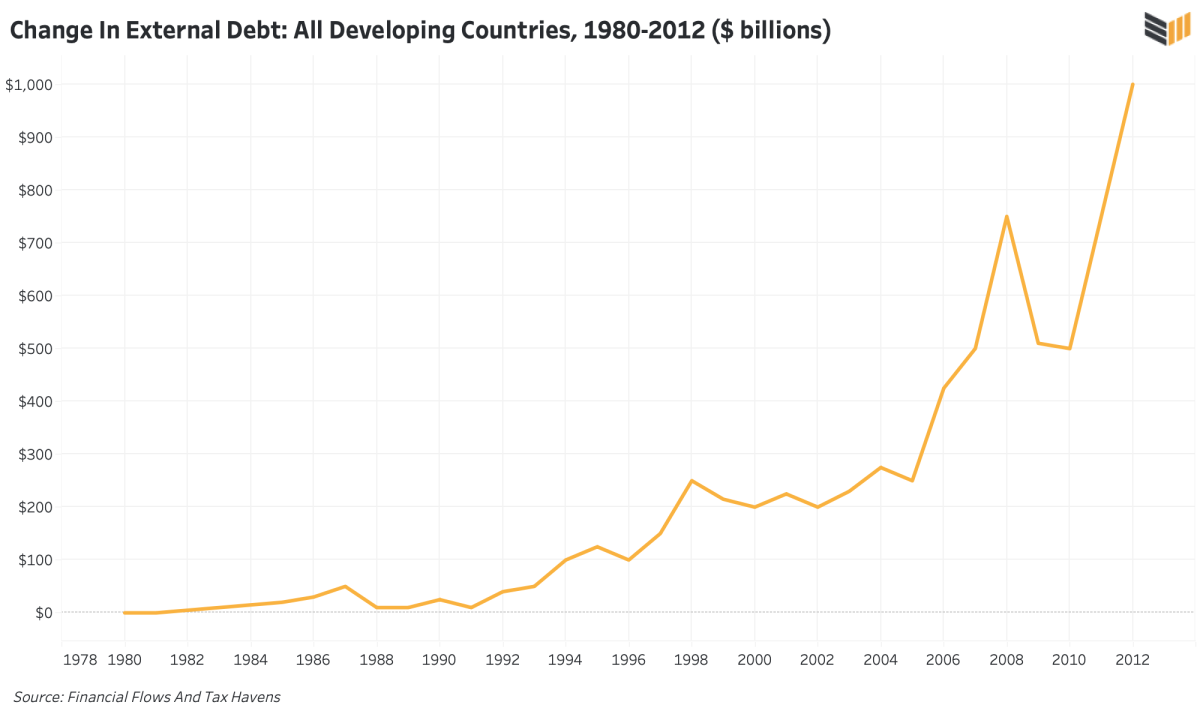

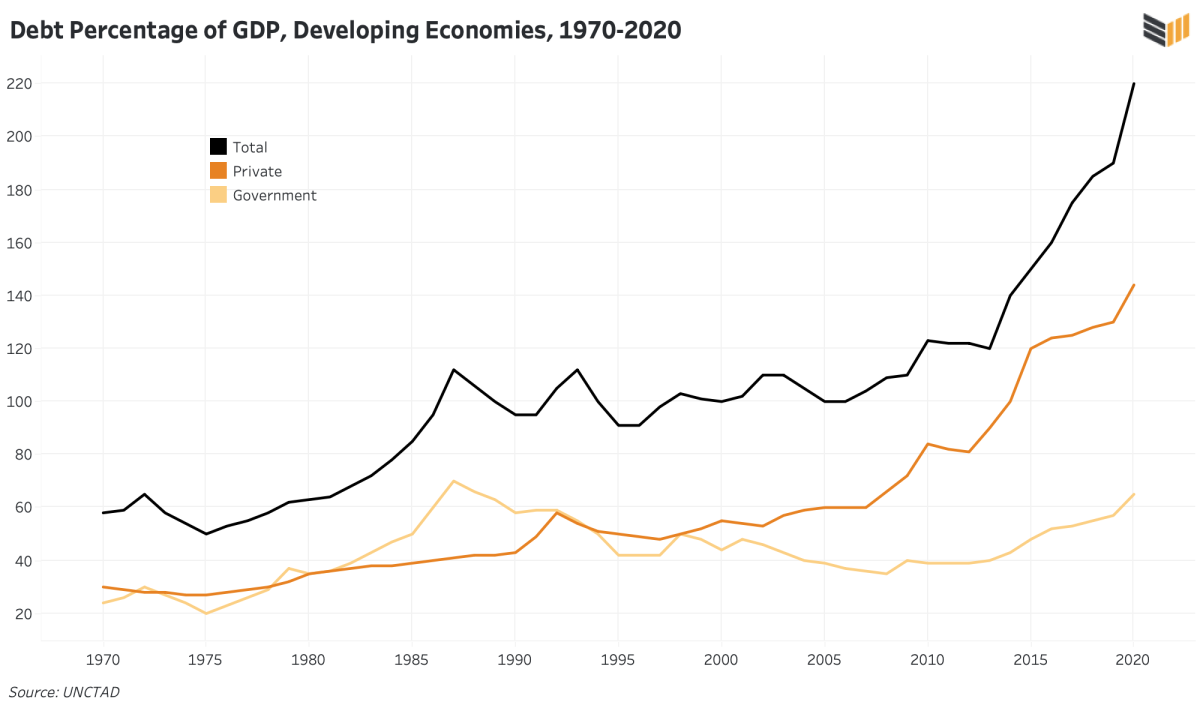

Dal 1970, il debito pubblico estero dei paesi in via di sviluppo è aumentato da 46 miliardi di dollari a $8,7 trilioni. Negli ultimi 50 anni, paesi come l’India, le Filippine e il Congo ora devono ai loro ex padroni coloniali 189 volte l’importo dovuto nel 1970. Hanno pagato $4,2 trilioni sui soli pagamenti di interessi dal 1980.

L’aumento esponenziale nel debito dei paesi in via di sviluppo

Even Payer — il cui libro del 1974 “The Debt Trap” utilizzava i dati del flusso economico per mostrare come il FMI ha irretito i paesi poveri incoraggiandoli a prendere in prestito più di quanto potrebbero eventualmente restituire — rimarrebbe scioccata dalle dimensioni della trappola del debito odierna.

La sua osservazione secondo cui”il cittadino medio degli Stati Uniti o dell’Europa potrebbe non essere consapevole di questo enorme drenaggio di capitali da parti del mondo che ritiene essere piti completamente povero” suona vero ancora oggi. Con vergogna di questo autore, non conosceva la vera natura del flusso globale di fondi e presumeva semplicemente che i paesi ricchi sovvenzionassero quelli poveri prima di intraprendere la ricerca per questo progetto. Il risultato finale è un letterale schema Ponzi, in cui negli anni’70 il debito del Terzo Mondo era così grande che era possibile pagare solo con nuovo debito. Da allora è sempre stato lo stesso.

Molti critici della Banca e del Fondo presumono che queste istituzioni stiano lavorando con il cuore nel posto giusto e, quando falliscono, è a causa di errori, sprechi o cattiva gestione.

La tesi di questo saggio è che ciò non è vero e che gli obiettivi fondamentali del Fondo e della Banca non sono riparare la povertà, ma piuttosto arricchire le nazioni creditrici a spese di quelle povere.

Questo autore semplicemente non è disposto a credere che un flusso permanente di fondi dai paesi poveri a quelli ricchi dal 1982 sia un”errore”. Il lettore può contestare che l’accordo sia intenzionale, e piuttosto può credere che sia un risultato strutturale inconscio. La differenza conta poco per i miliardi di persone che la Banca e il Fondo hanno impoverito.

V. Sostituzione del consumo di risorse coloniali

“Sono così stanco di aspettare. Non lo sei, perché il mondo diventi buono, bello e gentile? Prendiamo un coltello e tagliamo il mondo in due-e vediamo cosa stanno mangiando i vermi sulla scorza.

Alla fine degli anni’50, l’Europa e il Giappone si erano in gran parte ripresi dalla guerra e avevano ripreso una significativa crescita industriale, mentre i paesi del Terzo Mondo erano rimasti senza fondi. Pur avendo bilanci sani negli anni’40 e all’inizio degli anni’50, i paesi poveri esportatori di materie prime si sono imbattuti in problemi di bilancia dei pagamenti quando il valore delle loro merci è crollato sulla scia della guerra di Corea. Questo è quando è iniziata la trappola del debito e quando la Banca e il Fondo hanno aperto le cateratte di ciò che sarebbe finito per diventare trilioni di dollari di prestiti.

Questa era ha anche segnato la fine ufficiale del colonialismo, mentre gli imperi europei attiravano di ritorno dai loro possedimenti imperiali. L’assunto nello sviluppo internazionale è che il successo economico delle nazioni è dovuto “principalmente alle loro condizioni interne, domestiche. I paesi ad alto reddito hanno raggiunto il successo economico”, prosegue la teoria, “grazie al buon governo, alle istituzioni forti e ai mercati liberi. I paesi a basso reddito non sono riusciti a svilupparsi perché mancano di queste cose o perché soffrono di corruzione, burocrazia e inefficienza».

Questo è certamente vero. Ma un altro motivo importante per cui i paesi ricchi sono ricchi e i paesi poveri sono poveri è che i primi hanno saccheggiato i secondi per centinaia di anni durante il periodo coloniale.

“La rivoluzione industriale della Gran Bretagna”, Jason Hickel scrive,”dipendeva in gran parte dal cotone, che veniva coltivato su terreni sottratti con la forza agli indigeni americani , con manodopera sottratta agli schiavi africani. Altri input cruciali richiesti dai produttori britannici-canapa, legname, ferro, grano-sono stati prodotti utilizzando il lavoro forzato nelle tenute dei servi in Russia e nell’Europa orientale. Nel frattempo, l’estrazione britannica dall’India e da altre colonie ha finanziato più della metà del bilancio interno del paese, pagando strade, edifici pubblici, lo stato sociale-tutti i mercati dello sviluppo moderno-consentendo l’acquisto di input materiali necessari per l’industrializzazione. p>

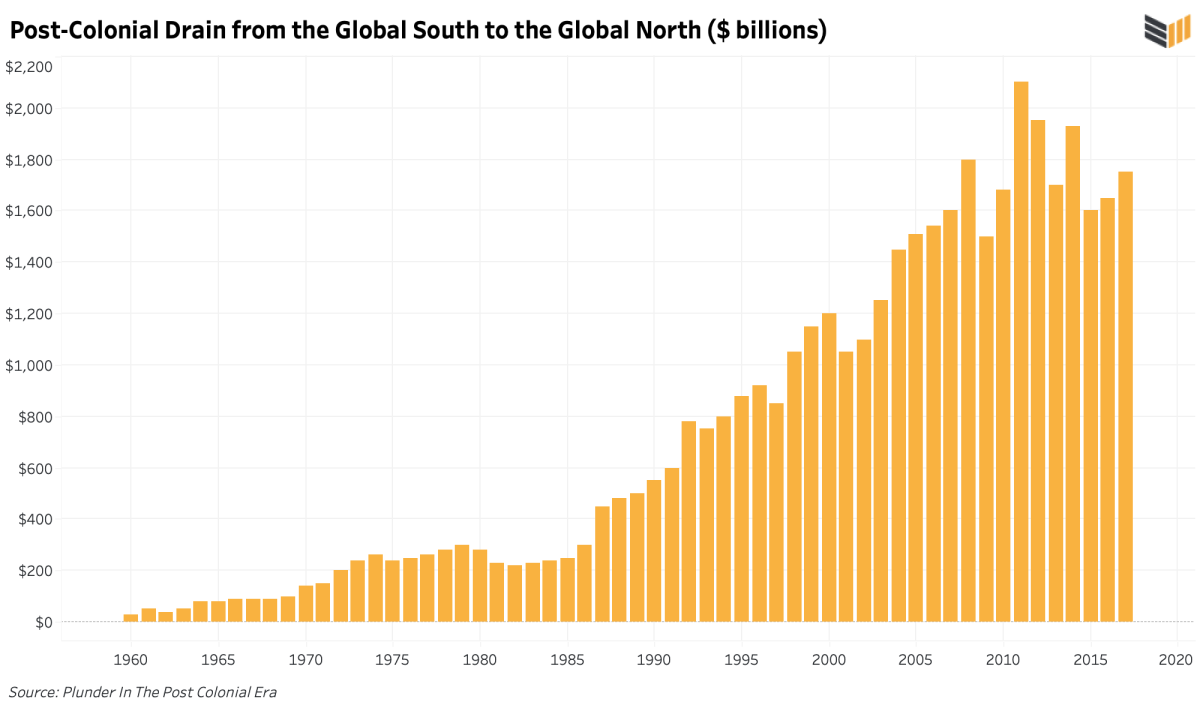

La dinamica del furto è stata descritta da Utsa e Prabhat Patnaik nel loro libro”Capital And Imperialism”: le potenze coloniali come l’impero britannico userebbero la violenza per estrarre materie prime dai paesi deboli, creando una”fuga coloniale”di capitale che vita potenziata e sovvenzionata a Londra, Parigi e Berlino. Le nazioni industriali trasformerebbero queste materie prime in manufatti e le rivenderebbero alle nazioni più deboli, traendo enormi profitti e spiazzando anche la produzione locale. E-in modo critico-manterrebbero bassa l’inflazione interna sopprimendo i salari nei territori coloniali. O attraverso la vera e propria schiavitù o pagando ben al di sotto del tasso di mercato globale.

Quando il sistema coloniale iniziò a vacillare, il mondo finanziario occidentale affrontò una crisi. I Patnaik sostengono che la Grande Depressione fu il risultato non solo di cambiamenti nella politica monetaria occidentale, ma anche del rallentamento della fuga coloniale. Il ragionamento è semplice: i paesi ricchi avevano costruito un nastro trasportatore di risorse provenienti dai paesi poveri, e quando il nastro si è rotto, si è rotto anche tutto il resto. Tra gli anni’20 e’60, il colonialismo politico si è praticamente estinto. Gran Bretagna, Stati Uniti, Germania, Francia, Giappone, Paesi Bassi, Belgio e altri imperi furono costretti a rinunciare al controllo su più della metà del territorio e delle risorse del mondo.

Come scrivono i Patnaik, l’imperialismo è”un accordo per imporre la deflazione del reddito alla popolazione del Terzo Mondo al fine di ottenere i loro beni primari senza incorrere nel problema dell’aumento del prezzo dell’offerta.

Dopo il 1960, questa è diventata la nuova funzione della Banca mondiale e del FMI: ricreare la fuga coloniale dai paesi poveri ai paesi ricchi che un tempo era mantenuta da un semplice imperialismo.

Drenaggio post-coloniale dal Dal Sud del mondo al Nord del mondo

I funzionari di Stati Uniti, Europa e Giappone volevano raggiungere un”equilibrio interno”, in altre parole, la piena occupazione. Ma si sono resi conto che non potevano farlo tramite sussidi all’interno di un sistema isolato, altrimenti l’inflazione sarebbe dilagante. Per raggiungere il loro obiettivo sarebbe necessario un contributo esterno da parte dei paesi più poveri. Il valore aggiunto in più estratta dal nucleo dai lavoratori della periferia è nota come “rendita imperialista”. Se i paesi industriali potessero ottenere materiali e manodopera più economici, e poi rivendere i prodotti finiti con un profitto, potrebbero avvicinarsi all’economia dei sogni dei tecnocrati. E hanno realizzato il loro desiderio: a partire dal 2019, i salari pagati ai lavoratori nei paesi in via di sviluppo erano Il 20% del livello dei salari pagati ai lavoratori nel mondo sviluppato.

Come esempio di come la Banca abbia ricreato la dinamica della fuga coloniale, Payer cita il caso classico della Mauritania degli anni’60 nell’Africa nordoccidentale. Un progetto minerario chiamato MIFERMA fu firmato dagli occupanti francesi prima che la colonia diventasse indipendente. L’accordo alla fine divenne”solo un progetto di enclave vecchio stile: una città in un deserto e una ferrovia che porta all’oceano”, poiché l’infrastruttura era focalizzata esclusivamente sul trasporto di minerali verso i mercati internazionali. Nel 1969, quando la miniera rappresentava il 30% del PIL della Mauritania e il 75% delle sue esportazioni, il 72% del reddito veniva inviato all’estero e”praticamente tutto il reddito distribuito localmente ai dipendenti evaporava in importazioni”. Quando i minatori hanno protestato contro l’accordo neocoloniale, le forze di sicurezza li hanno selvaggiamente repressi.

Geografia del drenaggio dal Sud del mondo dal 1960 al 2017

MIFERMA è un esempio stereotipato del tipo di”sviluppo” che verrebbe imposto al Terzo Mondo ovunque, dalla Repubblica Dominicana al Madagascar alla Cambogia. E di questi progetti si espansero rapidamente negli anni’70, grazie al sistema del petrodollaro.

Dopo il 1973, i paesi arabi dell’OPEC con enormi eccedenze derivanti dall’aumento vertiginoso dei prezzi del petrolio investirono i loro profitti in depositi e tesorerie nelle banche occidentali, che avevano bisogno un luogo dove prestare le loro crescenti risorse. I dittatori militari in America Latina, Africa e Asia si sono fatti ottimi obiettivi: avevano preferenze temporali elevate ed erano felici di prendere in prestito contro le generazioni future.

A contribuire ad accelerare la crescita dei prestiti è stata la”put del FMI”: le banche private hanno iniziato a crederci (correttamente) che il FMI salverebbe i paesi in caso di default, proteggendo i loro investimenti. Inoltre, i tassi di interesse a metà degli anni’70 erano spesso in territorio reale negativo, incoraggiando ulteriormente i mutuatari. Questo, combinato con l’insistenza del presidente della Banca mondiale Robert McNamara affinché l’assistenza si espandesse notevolmente, ha provocato una frenesia del debito. Le banche statunitensi, ad esempio, tra il 1978 e il 1982 hanno aumentato del 300% il loro portafoglio di prestiti del Terzo Mondo, portandolo a 450 miliardi di dollari.

Il problema era che questi prestiti erano in gran parte contratti a tasso d’interesse variabile, e pochi anni dopo , quei tassi sono esplosi quando la Federal Reserve americana ha aumentato il costo globale del capitale vicino al 20%. Il crescente peso del debito combinato con lo shock del prezzo del petrolio del 1979 e la conseguente il crollo del prezzo delle materie prime che alimentano il valore delle esportazioni dei paesi in via di sviluppo ha aperto la strada alla crisi del debito del terzo mondo. A peggiorare le cose, ben poco del denaro preso in prestito dai governi durante la frenesia del debito è stato effettivamente investito nel cittadino medio.

Il servizio del debito del Terzo mondo nel tempo

Nel loro Libro giustamente intitolato”Debt Squads”, i giornalisti investigativi Sue Branford e Bernardo Kucinski spiegano che tra il 1976 e il 1981, i governi latini (di cui 18 su 21 erano dittature) hanno preso in prestito 272,9 miliardi di dollari. Di questi, il 91,6% è stato speso per il servizio del debito, la fuga di capitali e la costituzione di riserve di regime. Solo l’8,4% è stato utilizzato per investimenti nazionali e, anche di questi, molto è stato sprecato.

Carlos Ayuda, sostenitore della società civile brasiliana, descrisse l’effetto del drenaggio alimentato dai petrodollari sul proprio paese:

“La dittatura militare ha utilizzato i prestiti per investire in enormi progetti infrastrutturali, in particolare progetti energetici… l’idea alla base della creazione di un’enorme diga e impianto idroelettrico nel mezzo dell’Amazzonia, ad esempio, era quella di produrre alluminio per l’esportazione nel nord… il governo ha contratto enormi prestiti e ha investito miliardi di dollari nella costruzione della diga di Tucuruí alla fine degli anni’70, distruggendo le foreste native e rimuovendo un numero enorme di popolazioni native e popolazioni rurali povere che vivevano lì da generazioni. Il governo avrebbe raso al suolo le foreste, ma le scadenze erano così brevi che hanno usato l’Agente Arancio per defogliare la regione e poi hanno immerso sott’acqua i tronchi degli alberi spogli… della produzione è stata di $ 48. Quindi i contribuenti hanno fornito sussidi, finanziando energia a basso costo per le multinazionali per vendere il nostro alluminio sul mercato internazionale.”

In altre parole, il popolo brasiliano ha pagato creditori stranieri per il servizio di distruzione del proprio ambiente , spostando le masse e vendendo le loro risorse.

Oggi il drenaggio dai paesi a basso e medio reddito è sbalorditivo. Nel 2015, ha totalizzato 10,1 miliardi di tonnellate di materie prime e 182 milioni di persone-anni di lavoro: il 50% di tutti i beni e il 28% di tutto il lavoro utilizzati quell’anno dai paesi ad alto reddito.

VI. A Dance With Dictators

“Potrebbe essere un figlio di puttana, ma è nostro figlio di puttana.”

Naturalmente, ci vogliono due parti per finalizzare un prestito dalla Banca o dal Fondo. Il problema è che il mutuatario è in genere un leader non eletto o irresponsabile, che prende la decisione senza consultare e senza un mandato popolare da parte dei propri cittadini.

Come scrive Payer in”The Debt Trap”,”I programmi del FMI sono politicamente impopolari, per le ottime ragioni concrete che danneggiano gli affari locali e deprimono il reddito reale dell’elettorato. È probabile che un governo che tenti di soddisfare le condizioni nella sua lettera di intenti all’FMI si ritroverà votato fuori sede.”

Pertanto, l’FMI preferisce lavorare con clienti non democratici che possono licenziare più facilmente giudici fastidiosi e reprimere le proteste di piazza. Secondo Payer, i colpi di stato militari in Brasile nel 1964, in Turchia nel 1960, in Indonesia nel 1966, in Argentina nel 1966 e nelle Filippine nel 1972 sono stati esempi di leader contrari al FMI sostituiti con la forza da altri favorevoli al FMI. Anche se il Fondo non è stato direttamente coinvolto nel colpo di stato, in ognuno di questi casi è arrivato con entusiasmo pochi giorni, settimane o mesi dopo per aiutare il nuovo regime ad attuare aggiustamenti strutturali.

La Banca e il Fondo condividono la volontà di sostenere governi violenti. Forse sorprendentemente, è stata la Banca a dare inizio alla tradizione. Secondo il ricercatore per lo sviluppo Kevin Danaher, “il triste record della Banca nel sostenere regimi e governi militari che hanno apertamente violato i diritti umani è iniziato il 7 agosto 1947, con un prestito per la ricostruzione di 195 milioni di dollari ai Paesi Bassi. Diciassette giorni prima che la Banca approvasse il prestito, i Paesi Bassi avevano scatenato una guerra contro i nazionalisti anticolonialisti nel loro enorme impero d’oltremare nelle Indie Orientali, che aveva già dichiarato la propria indipendenza come Repubblica di Indonesia.”

“Gli olandesi”, scrive Danaher, “inviarono 145.000 soldati (da una nazione con solo 10 milioni di abitanti all’epoca, economicamente in difficoltà al 90% della produzione del 1939) e lanciarono un blocco economico totale delle aree controllate dai nazionalisti, causando una notevole fame e problemi di salute tra i 70 milioni di abitanti dell’Indonesia.”

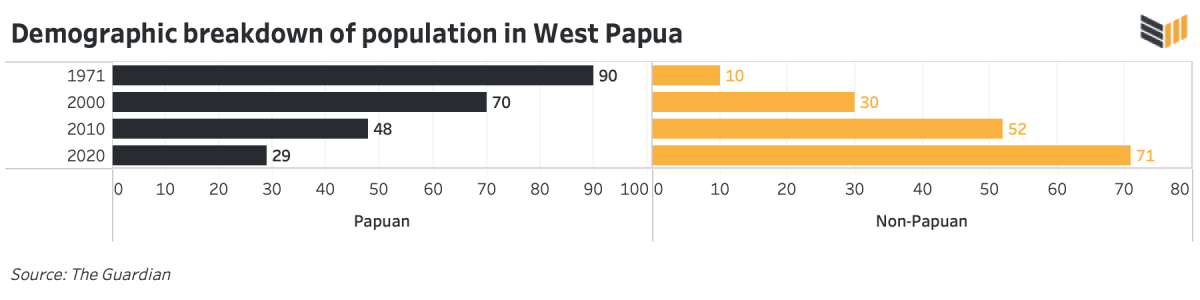

Nei suoi primi decenni la Banca ha finanziato molti di questi schemi coloniali, tra cui $28 milioni per la Rhodesia dell’apartheid nel 1952, così come prestiti a Australia, Regno Unito e Belgio per”sviluppare”i possedimenti coloniali in Papua Nuova Guinea, Kenya e il Congo belga.

Nel 1966, la Banca sfidò direttamente le Nazioni Unite,”continuando a prestare denaro al Sudafrica e al Portogallo nonostante le risoluzioni dell’Assemblea generale che invitavano tutte le agenzie affiliate alle Nazioni Unite a cessare il sostegno finanziario per entrambi i paesi”, secondo Danaher.

Danaher scrive che”il dominio coloniale del Portogallo su Angola e Mozambico e l’apartheid del Sud Africa sono state flagranti violazioni della Carta delle Nazioni Unite. Ma la Banca ha sostenuto che l’Articolo IV, Sezione 10 della sua Carta, che proibisce l’interferenza negli affari politici di qualsiasi membro, la obbligava legalmente a ignorare le risoluzioni delle Nazioni Unite. Di conseguenza, dopo l’approvazione della risoluzione delle Nazioni Unite, la Banca ha approvato prestiti di 10 milioni di dollari al Portogallo e di 20 milioni di dollari al Sudafrica.”

A volte, la preferenza della Banca per la tirannia era netta: interrompeva i prestiti alle persone democraticamente-eletto governo Allende in Cile all’inizio degli anni’70, ma poco dopo iniziò a prestare enormi quantità di denaro alla Romania di Ceausescu, uno dei peggiori stati di polizia del mondo. Questo è anche un esempio di come la Banca e il Fondo, contrariamente alla credenza popolare, non si limitassero a prestare secondo le linee ideologiche della Guerra Fredda: per ogni cliente di destra Augusto Pinochet Ugarte o Jorge Rafael Videla, c’era un Josip Broz di sinistra Tito o Julius Nyerere.

Nel 1979, osserva Danaher, 15 dei governi più repressivi del mondo avrebbero ricevuto un terzo intero di tutti i prestiti bancari. Questo anche dopo che il Congresso degli Stati Uniti e l’amministrazione Carter avevano interrotto gli aiuti a quattro dei 15-Argentina, Cile, Uruguay ed Etiopia-per”flagranti violazioni dei diritti umani”. Solo pochi anni dopo, in El Salvador, il FMI ha fatto un $ 43 milioni alla dittatura militare, solo pochi mesi dopo che le sue forze hanno commesso il più grande massacro nell’America Latina dell’era della Guerra Fredda annientando il villaggio di El Mozote.

Sono stati scritti diversi libri sulla Banca e il Fondo nel 1994, cronometrati come retrospettive di 50 anni sulle istituzioni di Bretton Woods. “Perpetuating Poverty” di Ian Vàsquez e Doug Bandow è uno di questi studi, ed è un particolarmente prezioso in quanto fornisce un’analisi libertaria. La maggior parte degli studi critici sulla Banca e sul Fondo sono di sinistra: ma Vásquez e Bandow del Cato Institute hanno individuato molti degli stessi problemi.

“Il Fondo sostiene qualsiasi governo”, scrivono,”per quanto venale e brutale … Alla fine del 1989 la Cina doveva al Fondo 600 milioni di dollari; nel gennaio 1990, pochi mesi dopo che il sangue si era asciugato in piazza Tiananmen a Pechino, il Fmi tenne un seminario sulla politica monetaria nella città”.

Vásquez e Bandow menzionano altri clienti tirannici che vanno dalla Birmania militare, al Cile di Pinochet, al Laos, al Nicaragua sotto Anastasio Somoza Debayle e ai sandinisti, alla Siria e al Vietnam.

“Il FMI”, dicono,”raramente ha incontrato una dittatura che non gli piaceva.”

Vásquez e Bandow dettagli della relazione della Banca con il regime marxista-leninista Mengistu Haile Mariam in Etiopia, dove ha fornito fino al 16% del bilancio annuale del governo mentre aveva uno dei peggiori record di diritti umani al mondo. Il credito della Banca è arrivato proprio mentre le forze di Mengistu stavano”radunando le persone nei campi di concentramento e nelle fattorie collettive”. Sottolineano anche come la Banca abbia dato al regime sudanese 16 milioni di dollari mentre stava cacciando 750.000 profughi da Khartoum nel deserto, e come abbia dato centinaia di milioni di dollari all’Iran-una brutale dittatura teocratica-e al Mozambico, le cui forze di sicurezza erano famigerato per torture, stupri ed esecuzioni sommarie.

Nel suo libro del 2011″Defeating Dictators”, il celebre economista dello sviluppo ghanese George Ayittey ha dettagliato un lungo elenco di”autocrati che ricevono aiuti”: Paul Biya, Idriss Déby, Lansana Conté, Paul Kagame, Yoweri Museveni, Hun Sen, Islam Karimov, Nursultan Nazarbayev e Emomali Rahmon. Ha sottolineato che il Fondo aveva erogato 75 miliardi di dollari solo a questi nove tiranni.

Nel 2014, un rapporto è stato pubblicato dall’International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, in cui si afferma che il governo etiope aveva utilizzato parte di un prestito bancario di 2 miliardi di dollari per forzare trasferire 37.883 famiglie indigene Anuak. Questo era il 60% dell’intera provincia di Gambella del paese. I soldati “picchiarono, violentarono e uccisero” Anuak che si rifiutava di lasciare le proprie case. Le atrocità sono state così male che il Sud Sudan abbia concesso lo status di rifugiato agli Anuak che arrivavano dalla vicina Etiopia. Human Rights Watch report said that the stolen land was then “leased by the government to investors” and that the Bank’s money was “used to pay the salaries of government officials who helped carry out the evictions.” The Bank approved new funding for this “villagization” program even after allegations of mass human rights violations emerged.

Mobutu Sese Soko and Richard Nixon at the White House in 1973

It would be a mistake to leave Mobutu Sese Soko’s Zaire out of this essay. The recipient of billions of dollars of Bank and Fund credit during his bloody 32-year reign, Mobutu pocketed 30% of incoming aid and assistance and let his people starve. He complied with 11 IMF structural adjustments: during one in 1984, 46,000 public school teachers were fired and the national currency was devalued by 80%. Mobutu called this austerity “a bitter pill which we have no alternative but to swallow,” but didn’t sell any of his 51 Mercedes, any of his 11 chateaus in Belgium or France, or even his Boeing 747 or 16th century Spanish castle.

Per capita income declined in each year of his rule on average by 2.2%, leaving more than 80% of the population in absolute poverty. Children routinely died before the age of five, and swollen-belly syndrome was rampant. It is estimated that Mobutu personally stole $5 billion, and presided over another $12 billion in capital flight, which together would have been more than enough to wipe the country’s $14 billion debt clean at the time of his ouster. He looted and terrorized his people, and could not have done it without the Bank and Fund, which continued to bail him out even though it was clear he would never repay his debts.

That all said, the true poster boy for the Bank and Fund’s affection for dictators might be Ferdinand Marcos. In 1966, when Marcos came to power, the Philippines was the second-most prosperous country in Asia, and the country’s foreign debt stood at roughly $500 million. By the time Marcos was removed in 1986, the debt stood at $28.1 billion.

As Graham Hancock writes in “Lords Of Poverty,” most of these loans”had been contracted to pay for extravagant development schemes which, although irrelevant to the poor, had pandered to the enormous ego of the head of state… a painstaking two-year investigation established beyond serious dispute that he had personally expropriated and sent out of the Philippines more than $10 billion. Much of this money — which of course, should have been at the disposal of the Philippine state and people — had disappeared forever in Swiss bank accounts.”

“$100 million,” Hancock writes, “was paid for the art collection for Imelda Marcos… her tastes were eclectic and included six Old Masters purchased from the Knodeler Gallery in New York for $5 million, a Francis Bacon canvas supplied by the Marlborough Gallery in London, and a Michelangelo, ‘Madonna and Child’ bought from Mario Bellini in Florence for $3.5 million.”

“During the last decade of the Marcos regime,” he says, “while valuable art treasuries were being hung on penthouse walls in Manhattan and Paris, the Philippines had lower nutritional standards than any other nation in Asia with the exception of war-torn Cambodia.”

To contain popular unrest, Hancock writes that Marcos banned strikes and “union organizing was outlawed in all key industries and in agriculture. Thousands of Filipinos were imprisoned for opposing the dictatorship and many were tortured and killed. Meanwhile the country remained consistently listed among the top recipients of both US and World Bank development assistance.”

After the Filipino people pushed Marcos out, they still had to pay an annual sum of anywhere between 40% and 50% of the entire value of their exports “just to cover the interest on the foreign debts that Marcos incurred.”

One would think that after ousting Marcos, the Filipino people would not have to owe the debt he incurred on their behalf without consulting them. But that is not how it has worked in practice. In theory, this concept is called “odious debt” and was invented by the U.S. in 1898 when it repudiated Cuba’s debt after Spanish forces were ousted from the island.

American leaders determined that debts “incurred to subjugate a people or to colonize them” were not legitimate. But the Bank and Fund have never followed this precedent during their 75 years of operations. Ironically, the IMF has an article on its website suggesting that Somoza, Marcos, Apartheid South Africa, Haiti’s “Baby Doc” and Nigeria’s Sani Abacha all borrowed billions illegitimately, and that the debt should be written off for their victims, but this remains a suggestion unfollowed.

Technically and morally speaking, a large percentage of Third World debt should be considered “odious” and not owed anymore by the population should their dictator be forced out. After all, in most cases, the citizens paying back the loans didn’t elect their leader and didn’t choose to borrow the loans that they took out against their future.

In July 1987, the revolutionary leader Thomas Sankara gave a speech to the Organistion of African Unity (OAU) in Ethiopia, where he refused to pay the colonial debt of Burkina Faso, and encouraged other African nations to join him.

“We cannot pay,” he said, “because we are not responsible for this debt.”

Sankara famously boycotted the IMF and refused structural adjustment. Three months after his OAU speech, he was assassinated by Blaise Compaoré, who would install his own 27-year military regime that would receive four structural adjustment loans from the IMF and borrow dozens of times from the World Bank for various infrastructure and agriculture projects. Since Sankara’s death, few heads of state have been willing to take a stand to repudiate their debts.

Burkinese dictator Blaise Compaoré and IMF managing director Dominique Strauss-Kahn. Compaoré seized power after assassinating Thomas Sankara (who tried to refuse Western debt) and he went on to borrow billions from the Bank and Fund.

One big exception was Iraq: after the U.S. invasion and ouster of Saddam Hussein in 2003, American authorities managed to get some of the debt incurred by Hussein to be considered “odious” and forgiven. But this was a unique case: for the billions of people who suffered under colonialists or dictators, and have since been forced to pay their debts plus interest, they have not gotten this special treatment.

In recent years, the IMF has even acted as a counter-revolutionary force against democratic movements. In the 1990s, the Fund was widely criticized on the left and the right for helping to destabilize the former Soviet Union as it descended into economic chaos and congealed into Vladimir Putin’s dictatorship. In 2011, as the Arab Spring protests emerged across the Middle East, the Deauville Partnership with Arab Countries in Transition was formed and met in Paris.

Through this mechanism, the Bank and Fund led massive loan offers to Yemen, Tunisia, Egypt, Morocco and Jordan — “Arab countries in transition” — in exchange for structural adjustment. As a result, Tunisia’s foreign debt skyrocketed, triggering two new IMF loans, marking the first time that the country had borrowed from the Fund since 1988. The austerity measures paired with these loans forced the devaluation of the Tunisian dinar, which spiked prices. National protests broke out as the government continued to follow the Fund playbook with wage freezes, new taxes and “early retirement” in the public sector.

Twenty-nine-year-old protestor Warda Atig summed up the situation: “As long as Tunisia continues these deals with the IMF, we will continue our struggle,” she said. “We believe that the IMF and the interests of people are contradictory. An escape from submission to the IMF, which has brought Tunisia to its knees and strangled the economy, is a prerequisite to bring about any real change.”

VII. Creating Agricultural Dependence

“The idea that developing countries should feed themselves is an anachronism from a bygone era. They could better ensure their food security by relying on the U.S. agricultural products, which are available in most cases at lower cost.”

As a result of Bank and Fund policy, all across Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and South and East Asia, countries which once grew their own food now import it from rich countries. Growing one’s own food is important, in retrospect, because in the post-1944 financial system, commodities are not priced with one’s local fiat currency: they are priced in the dollar.

Consider the price of wheat, which ranged between $200 and $300 between 1996 and 2006. It has since skyrocketed, peaking at nearly $1,100 in 2021. If your country grew its own wheat, it could weather the storm. If your country had to import wheat, your population risked starvation. This is one reason why countries like Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Egypt, Ghana and Bangladesh are all currently turning to the IMF for emergency loans.

Historically, where the Bank did give loans, they were mostly for “modern,” large-scale, mono-crop agriculture and for resource extraction: not for the development of local industry, manufacturing or consumption farming. Borrowers were encouraged to focus on raw materials exports (oil, minerals, coffee, cocoa, palm oil, tea, rubber, cotton, etc.), and then pushed to import finished goods, foodstuffs and the ingredients for modern agriculture like fertilizer, pesticides, tractors and irrigation machinery. The result is that societies like Morocco end up importing wheat and soybean oil instead of thriving on native couscous and olive oil, “fixed” to become dependent. Earnings were typically used not to benefit farmers, but to service foreign debt, purchase weapons, import luxury goods, fill Swiss bank accounts and put down dissent.

Consider some of the world’s poorest countries. As of 2020, after 50 years of Bank and Fund policy, Niger’s exports were 75% uranium; Mali’s 72% gold; Zambia’s 70% copper; Burundi’s 69% coffee; Malawi’s 55% tobacco; Togo’s 50% cotton; and on it goes. At times in past decades, these single exports supported virtually all of these countries’ hard currency earnings. This is not a natural state of affairs. These items are not mined or produced for local consumption, but for French nuclear plants, Chinese electronics, German supermarkets, British cigarette makers, and American clothing companies. In other words, the energy of the labor force of these nations has been engineered toward feeding and powering other civilizations, instead of nourishing and advancing their own.

Researcher Alicia Koren wrote about the typical agricultural impact of Bank policy in Costa Rica, where the country’s “structural adjustment called for earning more hard currency to pay off foreign debt; forcing farmers who traditionally grew beans, rice, and corn for domestic consumption to plant non-traditional agricultural exports such as ornamental plants, flowers, melons, strawberries, and red peppers… industries that exported their products were eligible for tariff and tax exemptions not available to domestic producers.”

“Meanwhile,” Koren wrote, “structural adjustment agreements removed support for domestic production… while the North pressured Southern nations to eliminate subsidies and ‘barriers to trade,’ Northern governments pumped billions of dollars into their own agricultural sectors, making it impossible for basic grains growers in the South to compete with the North’s highly subsidized agricultural industry.”

Koren extrapolated her Costa Rica analysis to make a broader point: “Structural adjustment agreements shift public spending subsidies from basic supplies, consumed mainly by the poor and middle classes, to luxury export crops produced for affluent forei gners.” Third World countries were not seen as body politics but as companies that needed to increase revenues and decrease expenditures.

The testimony of a former Jamaican official is especially telling: “We told the World Bank team that farmers could hardly afford credit, and that higher rates would put them out of business. The Bank told us in response that this means ‘The market is telling you that agriculture is not the way to go for Jamaica’ — they are saying we should give up farming altogether.”

“The World Bank and IMF,” the official said, “don’t have to worry about the farmers and local companies going out of business, or starvation wages or the social upheaval that will result. They simply assume that it is our job to keep our national security forces strong enough to suppress any uprising.”

Developing governments are stuck: faced with insurmountable debt, the only factor they really control in terms of increasing revenue is deflating wages. If they do this, they must provide basic food subsidies, or else they will be overthrown. And so the debt grows.

Even when developing countries try to produce their own food, they are crowded out by a centrally-planned global trade market. For example, one would think that the cheap labor in a place like West Africa would make it a better exporter of peanuts than the United States. But since Northern countries pay an estimated $1 billion in subsidies to their agriculture industries every single day, Southern countries often struggle to be competitive. What’s worse, 50 or 60 countries are often directed to focus on the very same crops, crowding each other out in the global marketplace. Rubber, palm oil, coffee, tea and cotton are Bank favorites, as the poor masses can’t eat them.

It is true that the Green Revolution has created more food for the planet, especially in China and East Asia. But despite advances in agricultural technology, much of these new yields go to exports, and vast swathes of the world remain chronically malnourished and dependent. To this day, for example, African nations import about 85% of their food. They pay more than $40 billion per year — a number estimated to reach $110 billion per year by 2025 — to buy from other parts of the world what they could grow themselves. Bank and Fund policy helped transform a continent of incredible agricultural riches into one reliant on the outside world to feed its people.

Reflecting on the results of this policy of dependency, Hancock challenges the widespread belief that the people of the Third World are “fundamentally helpless.”

“Victims of nameless crises, disasters, and catastrophes,” he writes, suffer from a perception that “they can do nothing unless we, the rich and powerful, intervene to save them from themselves.” But as evidenced by the fact that our “assistance” has only made them more dependent on us, Hancock rightfully unmasks the notion that “only we can save them” as “patronizing and profoundly fallacious.”

Far from playing the role of good samaritan, the Fund does not even follow the timeless human tradition, established more than 4,000 years ago by Hammurabi in ancient Babylon, of forgiving interest after natural disasters. In 1985, a devastating earthquake hit Mexico City, killing more than 5,000 people and causing $5 billion of damage. Fund staff — who claim to be saviors, helping to end poverty and save countries in crisis — arrived a few days later, demanding to be repaid.

VIII. You Can’t Eat Cotton

“Development prefers crops that can’t be eaten so the loans can be collected.”

–Cheryl Payer

The Togolese democracy advocate Farida Nabourema’s own personal and family experience tragically matches the big picture of the Bank and Fund laid out thus far.

The way she puts it, after the 1970s oil boom, loans were poured into developing nations like Togo, whose unaccountable rulers didn’t think twice about how they would repay the debt. Much of the money went into giant infrastructure projects that didn’t help the majority of the people. Much was embezzled and spent on pharaonic estates. Most of these countries, she says, were ruled by single party-states or families. Once interest rates started to hike, these governments could no longer pay their debts: the IMF started “taking over” by imposing austerity measures.

“These were new states that were very fragile,” Nabourema says in an interview for this article. “They needed to invest strongly in social infrastructure, just as the European states were allowed to do after World War II. But instead, we went from free healthcare and education one day, to situations the next where it became too costly for the average person to get even basic medicine.”

Regardless of what one thinks about state-subsidized medicine and schooling, eliminating it overnight was traumatic for poor countries. Bank and Fund officials, of course, have their own private healthcare solutions for their visits and their own private schools for their children whenever they have to live “in the field.”

Because of the forced cuts in public spending, Nabourema says, the state hospitals in Togo remain to this day in “complete decay.” Unlike the state-run, taxpayer-financed public hospitals in the capitals of former colonial powers in London and Paris, things are so bad in Togo’s capital Lomé that even water has to be prescribed.

“There was also,” Nabourema said, “reckless privatization of our public companies.” She explained how her father used to work at the Togolese steel agency. During privatization, the company was sold off to foreign actors for less than half of what the state built it for.

“It was basically a garage sale,” she said.

Nabourema says that a free market system and liberal reforms work well when all participants are on an equal playing field. But that is not the case in Togo, which is forced to play by different rules. No matter how much it opens up, it can’t change the strict policies of the U.S. and Europe, who aggressively subsidize their own industries and agriculture. Nabourema mentions how a subsidized influx of cheap used clothes from America, for example, ruined Togo’s local textile industry.

“These clothes from the West,” she said, “put entrepreneurs out of business and littered our beaches.”

The most horrible aspect, she said, is that the farmers — who made up 60% of the population in Togo in the 1980s — had their livelihoods turned upside down. The dictatorship needed hard currency to pay its debts, and could only do this by selling exports, so they began a massive campaign to sell cash crops. With the World Bank’s help, the regime invested heavily in cotton, so much so that it now dominates 50% of the country’s exports, destroying national food security.

In the formative years for countries like Togo, the Bank was the “largest single lender for agriculture.” Its strategy for fighting poverty was agricultural modernization: “massive transfers of capital, in the form of fertilizers, pesticides, earth-moving equipment, and expensive foreign consultants.”

Nabourema’s father was the one who revealed to her how imported fertilizers and tractors were diverted away from farmers growing consumption food, to farmers growing cash crops like cotton, coffee, cocoa and cashews. If someone was growing corn, sorghum or millet — the basic foodstuffs of the population — they didn’t get access.

“You can’t eat cotton,” Nabourema reminds us.

Over time, the political elite in countries like Togo and Benin (where the dictator was literally a cotton mogul) became the buyer of all the cash crops from all of the farms. They’d have a monopoly on purchases, Nabourema says, and would buy the crops for prices so low that the peasants would barely make any money. This entire system — called “sotoco” in Togo — was based on funding provided by the World Bank.

When farmers would protest, she said, they would get beaten or their farms would get burned to rubble. The y could have just grown normal food and fed their families, like they had done for generations. But now they could not even afford the land: the political elite has been acquiring land at an outrageous rate, often through illegal means, jacking up the price.

As an example, Nabourema explains how the Togolese regime might seize 2,000 acres of land: unlike in a liberal democracy (like the one in France, which has built its civilization off the backs of countries like Togo), the judicial system is owned by the government, so there is no way to push back. So farmers, who used to be self-sovereign, are now forced to work as laborers on someone else’s land to provide cotton to rich countries far away. The most tragic irony, Nabourema says, is that cotton is overwhelmingly grown in the north of Togo, in the poorest part of the country.

“But when you go there,” she says, “you see it has made no one rich.”

Women bear the brunt of structural adjustment. The misogyny of the policy is “quite clear in Africa, where women are the major farmers and providers of fuel, wood, and water,” Danaher writes. And yet, a recent retrospective says, “the World Bank prefers to blame them for having too many children rather than reexamining its own policies.”

As Payer writes, for many of the world’s poor, they are poor “not because they have been left behind or ignored by their country’s progress, but because they are the victims of modernisation. Most have been crowded off the good farmland, or deprived of land altogether, by rich elites and local or foreign agribusiness. Their destitution has not ‘ruled them out’ of the development process; the development process has been the cause of their destitution.”

“Yet the Bank,” Payer says, “is still determined to transform the agricultural practices of small farmers. Bank policy statements make it clear that the real aim is integration of peasant land into the commercial sector through the production of a ‘marketable surplus’ of cash crops.”

Payer observed how, in the 1970s and 1980s, many small plotters still grew the bulk of their own food needs, and were not “dependent on the market for the near-totality of their sustenance, as ‘modern’ people were.” These people, however, were the target of the Bank’s policies, which transformed them into surplus producers, and “often enforced this transformation with authoritarian methods.”

In a testimony in front of U.S. Congress in the 1990s, George Ayittey remarked that “if Africa were able to feed itself, it could save nearly $15 billion it wastes on food imports. This figure may be compared with the $17 billion Africa received in foreign aid from all sources in 1997.”

In other words, if Africa grew its own food, it wouldn’t need foreign aid. But if that were to happen, then poor countries wouldn’t be buying billions of dollars of food per year from rich countries, whose economies would shrink as a result. So the West strongly resists any change.

IX. The Development Set

Excuse me, friends, I must catch my jet

I’m off to join the Development Set

My bags are packed, and I’ve had all my shots

I have traveller’s checks and pills for the trots!

The Development Set is bright and noble

Our thoughts are deep and our vision global

Although we move with the better classes

Our thoughts are always with the masses

In Sheraton Hotels in scattered nations

We damn multinational corporations

Injustice seems easy to protest

In such seething hotbeds of social rest.

We discuss malnutrition over steaks

And plan hunger talks during coffee breaks.

Whether Asian floods or African drought

We face each issue with open mouth.

And so begins “The Development Set,” a 1976 poem by Ross Coggins that hits at the heart of the paternalistic and unaccountab le nature of the Bank and the Fund.

The World Bank pays high, tax-free salaries, with very generous benefits. IMF staff are paid even better, and traditionally were flown first or business class (depending on the distance), never economy. They stayed in five-star hotels, and even had a perk to get free upgrades onto the supersonic Concorde. Their salaries, unlike wages made by people living under structural adjustment, were not capped and always rose faster than the inflation rate.

Until the mid-1990s the janitors cleaning the World Bank headquarters in Washington — mostly immigrants who fled from countries that the Bank and Fund had “adjusted” — were not even allowed to unionize. In contrast, Christine Lagarde’s tax-free salary as head of the IMF was $467,940, plus an additional $83,760 allowance. Of course, during her term from 2011 to 2019, she oversaw a variety of structural adjustments on poor countries, where taxes on the most vulnerable were almost always raised.

Graham Hancock notes that redundancy payments at the World Bank in the 1980s “averaged a quarter of a million dollars per person.” When 700 executives lost their jobs in 1987, the money spent on their golden parachutes — $175 million — would have been enough, he notes, “to pay for a complete elementary school education for 63,000 children from poor families in Latin America or Africa.”

According to former World Bank head James Wolfensohn, from 1995 to 2005 there were more than 63,000 Bank projects in developing countries: the costs of “feasibility studies” and travel and lodging for experts from industrialized countries alone absorbed as much as 25% of the total aid.

Fifty years after the creation of the Bank and Fund, “90% of the $12 billion per year in technical assistance was still spent on foreign expertise.” That year, in 1994, George Ayittey noted that 80,000 Bank consultants worked on Africa alone, but that “less than.01%” were Africans.

Hancock writes that “the Bank, which puts more money into more schemes in more developing countries than any other institution, claims that ‘it seeks to meet the needs of the poorest people;’ but at no stage in what it refers to as the ‘project cycle’ does it actually take the time to ask the poor themselves how they perceive their needs… the poor are entirely left out of the decision-making progress — almost as if they don’t exist.”

Bank and Fund policy is forged in meetings in lavish hotels between people who will never have to live a day in poverty in their lives. As Joseph Stiglitz argues in his own criticism of the Bank and Fund, “modern high-tech warfare is designed to remove physical contact: dropping bombs from 50,000 feet ensures that one does not ‘feel’ what one does. Modern economic management is similar: from one’s luxury hotel, one can callously impose policies about which one would think twice if one knew the people whose lives one was destroying.”

Strikingly, Bank and Fund leaders are sometimes the very same people who drop the bombs. For example, Robert McNamara — probably the most transformative person in Bank history, famous for massively expanding its lending and sinking poor countries into inescapable debt — was first the CEO of the Ford corporation, before becoming U.S. defense secretary, where he sent 500,000 American troops to fight in Vietnam. After leaving the Bank, he went straight to the board of Royal Dutch Shell. A more recent World Bank head was Paul Wolfowitz, one of the key architects of the Iraq War.

The development set makes its decisions far away from the populations who end up feeling the impact, and they hide the details behind mountains of paperwork, reports and euphemistic jargon. Like the old British Colonial Office, the set conceals itself “like a cuttlefish, in a cloud of ink.”