Partie I : Bitcoin comme arbre, persistance et structures profondes

Une rêverie

Peut-être si J’avais été plus effronté, le titre de la première partie de cette série aurait fini par être quelque chose de plus alléchant, quelque chose de percutant comme”Bitcoin est un palmier, et Fiat est une noix de coco”. Mais pour le meilleur ou pour le pire, un tel titre semblait saturé d’un peu trop de légèreté, trop tropical et trivial pour un sujet aussi important.

En vérité cependant, l’imagerie du palmier aurait été en fait très précise allégorie de la façon dont la feuille de route bitcoin et fiat évoluera à mesure que nous progressons dans le 21e siècle. Un palmier royal, roystonea oleracea, se balançant fiévreusement dans une rafale torrentielle, mais ne cessant jamais de conserver une prise ferme à ses racines profondément sous le sol. Et comme pour toute tempête, la seule nécessité darwinienne pour cet arbre est celle de la survie, pour traverser la tempête le plus indemne possible.

D’autres arbres et structures peuvent se briser et se briser en capitulation face aux aléas de la nature, laissant plus de soleil à notre palmier royal une fois le ciel dégagé. Les débris de tout ce qui n’avait pas été assez robuste pour survivre à l’attaque, métabolisés par les colonies de termites et les feux de brousse, transformés en sol luxuriant et fertile. Une nouvelle couche de base à partir de laquelle reconstruire et prospérer. Une métaphore appropriée, à la lumière du fait que le sol se trouve être le seul milieu physique jamais observé dans la nature capable de transformer la mort en vie. De même, une monnaie saine absolument rare et incorruptible est le seul moyen économique capable d’insuffler une vie économique à un système financier en décomposition et dégradé.

Un avertissement

« Passer sans danger votre temps dans la prairie loin

Seulement conscient d’un certain malaise dans l’air

Vous feriez mieux de faire attention

Il peut y avoir des chiens à propos

J’ai regardé par-dessus la Jordanie, et j’ai vu

Les choses ne sont pas ce qu’elles semblent être

Qu’est-ce que vous obtenez pour prétendre que le danger n’est pas réel

Doux et obéissant, vous suivez le leader

Dans les couloirs bien fréquentés de la vallée de l’acier

Quelle surprise !

Un regard de choc terminal dans votre yeux

Maintenant, les choses sont vraiment ce qu’elles semblent être

Non, ce n’est pas un mauvais rêve”

-Roger Waters,”Sheep”, 1977

Source : Nareeta Martin, @LudiMagistR

Une prophétie

« Avez-vous entendu parler de la rose qui a poussé à partir d’une fissure dans le béton ?

Prouvant que les lois de la nature sont fausses, elle a appris à marcher sans avoir les pieds.

Drôle, c’est semble en gardant ses rêves, il a appris à respirer l’air frais.

Vive la rose qui a poussé du béton quand personne d’autre ne s’en souciait. »

–Tupac Shakur, « La rose qui a poussé du béton,” 1999

Avant de pouvoir pleinement apprécier la caractéristique de persistance du bitcoin inférée ci-dessus, il est peut-être utile de contextualiser comment et pourquoi une telle « antifragilité » (quelque chose que nous définirons plus en détail ci-dessous) se révélera inévitablement comme un coup de tonnerre, une gifle dans le visage, nous permettant à tous d’être témoin de son utilité profondément sous-estimée.

Pour ce faire, faisons un léger détour en utilisant une version modifiée de la technique du questionnement socratique.

Une théorie : la ruée de la classe des investisseurs de masse

L’investisseur estimé en technologie polymath Balaji Srinivasan, dans son modèle conceptuel d’une économie pseudonyme décentralisée, a déclaré de manière controversée :

« Dans les années 1800, tout le monde était un agriculteur. Dans les années 1900, tout le monde travaillait dans le secteur manufacturier. Dans les années 2000, tout le monde devient investisseur… Et l’une des choses que les gens ne comprennent pas tant qu’ils ne sont pas investisseur, c’est cette idée que l’argent est abondant.”

-Balaji Srinivasan,”Investir comme le meilleur podcast avec Patrick O’Shaughnessy“

Source : Balaji Srinivasan

A Discussion

Prenons l’énoncé ci-dessus pour argent comptant et acceptons-le pour le moment comme une réalité a priori évolutive. Je pense que la plupart d’entre nous conviendront qu’un tel élargissement de la portée de la classe des investisseurs connaît en effet une accélération rapide, s’accélérant en particulier dans le monde post-pandémique. Il est difficile de nier les preuves tangibles (discutées ci-dessous), ainsi que les projecteurs culturels observés qui ont mis l’accent sur l’investissement boursier autogéré. Les preuves sont partout, même en parcourant mon fil d’actualité pendant que j’écrivais cet essai :

« Robinhood travaille sur une fonctionnalité pour permettre aux utilisateurs d’investir des pièces de rechange »

« Investir des pièces de rechange a devient une stratégie de plus en plus populaire pour les nouveaux traders d’actions, et est un élément clé des applications concurrentes telles que Acorns, Chime et Wealthsimple.”

Avec l’introduction en bourse symbolique de Robinhood maintenant gravée dans notre mémoire récente, les titres comme indiqué ci-dessus sont des exemples parfaits pour notre discussion. L’investissement boursier microfinancé incarnerait cette évolution vers une classe d’investisseurs de masse. Pour ma part, je vois ce changement tout autour de moi, dans ma vie professionnelle dans le secteur des hedge funds, dans une culture de croissance du FOMO, de la cupidité et de l’anxiété, jusqu’à mes interactions personnelles avec mes amis et ma famille et sur les réseaux sociaux. Je crois même que c’est ce que de nombreux décideurs et technocrates aspirent consciemment à encourager. Et cela me dérange.

Quelles sont les implications d’une telle transformation sociétale ? Et quelles sont ses causes profondes ?

De telles questions ouvertes découlant de cette observation sont l’une des raisons pour lesquelles je suis si attiré et intrigué par la conjecture de Srinivasan en premier lieu. Sa déclaration ouvre la porte à une variété de discussions et aborde des thèmes très importants.

Certains de ces thèmes relatifs à l’inévitabilité d’une économie décentralisée sont des sujets qui seront discutés plus en détail dans la deuxième partie de cette série. En attendant, préparons le terrain en comprenant pourquoi une classe d’investisseurs de masse est encouragée, comment elle conduira à encore plus de centralisation et comment toutes ces portes ouvertes sont des escalators à sens unique, garantis pour conduire à d’autres arbres de décision dépendants du chemin. , et génèrent finalement une instabilité quasi infinie et une fragilité systémique.

Et ce qui deviendra extrêmement clair, ce sera l’interaction holistique entre l’inévitabilité et la non-durabilité de cette voie d’un côté de la médaille. Et puis la persistance du bitcoin de l’autre côté, attendant patiemment que son tour soit hissé dans les airs, tournant frénétiquement, bien que calme et serein alors qu’il anticipe patiemment un atterrissage face visible.

Une métaphore en sandwich

Ce que la prophétie de Srinivasan expose sans le savoir, c’est la réalité d’une période de transition dangereuse dans laquelle se trouve actuellement l’économie mondiale. Nous nous trouvons actuellement dans un état confus de limbes, pris en sandwich de manière précaire entre décentralisation et centralisation.

L’énergie culturelle de cet état temporel fluide sollicite certainement un certain « malaise dans l’air », bien que le mécontentement croissant soit palpable. Et tout comme les événements de la pandémie de COVID-19 ont propulsé l’intensification de nombreuses tendances, l’une de ces tendances est en effet la manifestation d’un « prolétariat » et d’une classe d’investisseurs en expansion agressive. Et bien qu’une telle progression ait de nombreux attributs positifs-allant de l’autonomisation à la possibilité de créer de nouvelles richesses à court terme et à l’éducation financière sur les marchés, la gestion des risques, l’argent et la théorie économique-tous ces avantages sont malheureusement malavisés et à court terme. voyant. En fin de compte, ces avantages très tangibles sont destinés à être dilués et vaincus par des forces de mauvais augure.

Les principales raisons pour lesquelles une banalisation de la classe des investisseurs est une évolution si dangereuse peuvent être principalement attribuées au timing, contexte historique, et les implications de ce que cette société d’investisseurs de masse aura besoin sous la forme d’effets dérivés de second et troisième.

Veuillez être patient ci-dessous, car cette première section est inévitablement lourde de données financières et de terminologie. Cependant, ces données sont impératives pour nous aider à comprendre l’ensemble de ce qui se passe et rapporteront des dividendes plus loin dans l’article et la série à mesure que nous développerons les idées plus larges de notre thèse.

Je ne suis pas un prophète de malheur. Je ne vis pas dans un bunker. J’ai vu trop d’investisseurs être victimes de récits trop baissiers, manquant de grandes inflations d’actifs qu’une telle négativité a obscurcies. Le but de cet essai, cependant, n’est pas d’exposer une thèse d’investissement à court terme. Cela dit, ce que j’ai commencé à constater avec une clarté croissante en tant qu’investisseur, en tant que membre de notre société qui se soucie du monde dont héritent mes enfants, est de plus en plus la preuve d’un piège inévitable. Un piège avec une seule solution réaliste. Ainsi, les données financières ici ne sont qu’un outil, un langage pour nous aider à voir cette idée. En fait, le message principal de cette série concerne beaucoup moins la finance et les marchés, et beaucoup plus la nature humaine, l’histoire et l’impact que les incitations et les conflits idéologiques auront sur l’issue de la majeure partie de ce siècle.

Alors, supportez-moi pendant que je nous emmène plus loin dans ce terrier de blocs du destin dans notre chaîne de réactions.

Bloc 1 : Le contexte historique compte. Il s’avère que le timing est primordial

Une classe d’investisseurs de masse, motivée par de fausses prémisses et des incitations perverses, se forme ironiquement après une période d’inflation historique sans précédent des actifs.

Nous venons d’assister à plus de 40 ans sans précédent d’inflation des actifs financiers, d’accumulation de dettes, de déréglementation et d’opulence monétaire. Un marché obligataire haussier épique où le taux sans risque est passé de 16% à près de zéro, le marché boursier par rapport à notre capacité de production est à un niveau record (voir le graphique ci-dessous), presque toutes les mesures de valorisation sont à des sommets historiques et un comportement irrationnel a s’est considérablement développé (comme en témoignent les SPAC, les r/WallStreetBets, les actions meme, la dette sur marge de détail et, bien sûr, de nombreuses poches de l’univers «crypto»).

Dans le même temps, l’effet de levier des gouvernements et des entreprises est également extrême. Ces statistiques deviennent encore plus excessives une fois que l’on tient compte des engagements publics hors bilan tels que la sécurité sociale, l’assurance-maladie, les obligations en matière de retraite et les budgets de défense hors bilan. Cela s’ajoute à la prise en compte d’hypothèses de conseils d’entreprise optimistes et à de nombreuses équipes de direction d’entreprise qui deviennent désespérément créatives avec des astuces d’ajout de bénéfices et des stratégies d’ingénierie comptable agressives. Autrement dit, l’investisseur individuel se professionnalise à la fin de l’une des plus grandes et des plus homériques soirées éclatantes de tous les temps. Pardonnez la métaphore du baseball cliché, mais c’est comme un joueur appelé des ligues mineures juste avant la saison morte, après une finale dramatique de sept matchs des World Series.

Est-ce vraiment un bon développement pour la société ? Ceci est en fait assez typique du comportement observé et de la participation qui se produit dans les périodes de pointe des marchés haussiers. Cependant, il existe ici quelques différences clés par rapport à l’éclatement typique d’une bulle.

Tout d’abord, nous faisons référence à un tel comportement dans le contexte de ces investissements réalisés sous le couvert d’un nouveau professionnalisme et de changements de carrière responsabilisés. Il existe un sentiment de droit à la richesse, et les décideurs politiques comme les nouveaux investisseurs s’attendent à ce qu’ils aient le droit de s’enrichir sur les marchés des capitaux, et ce avec très peu de risques inhérents. De plus, comme en témoigne la baisse du taux d’activité, une société d’investisseurs crée un double risque. Alors que de plus en plus de gens renoncent à d’autres modes de travail, nous devenons une société de « locataires » plutôt que de « faiteurs ». Nous renversons la flèche de l’histoire qui a toujours conduit à une spécialisation et une division du travail accrues. Ainsi, non seulement plus de personnes sont maintenant exposées aux actifs financiers que jamais auparavant, mais cette cohorte en expansion l’a fait au prix d’opportunité d’emplois perdus et de salaires gagnés ailleurs.

Les enjeux sont plus importants et la marge d’erreur plus faible. Et un tel comportement est en fait approuvé à la fois culturellement, comme un moyen de se révolter contre la classe riche, et politiquement, comme un droit libéral pour la propriété d’actifs à voir une plus grande distribution, sans aucun égard à la valeur et au risque sous-jacents de ces actifs. C’est différent d’une simple bulle financière transitoire. Il s’agit d’une montgolfière flottant dans la stratosphère, pour ne plus jamais sentir l’étreinte de la terre ferme.

US capitalisation boursière par rapport au PIB en dollars nominaux, de 1971 à aujourd’hui. Source : @LudiMagistR, Bloomberg

L’adoption de la classe d’investisseurs de masse s’accélère.

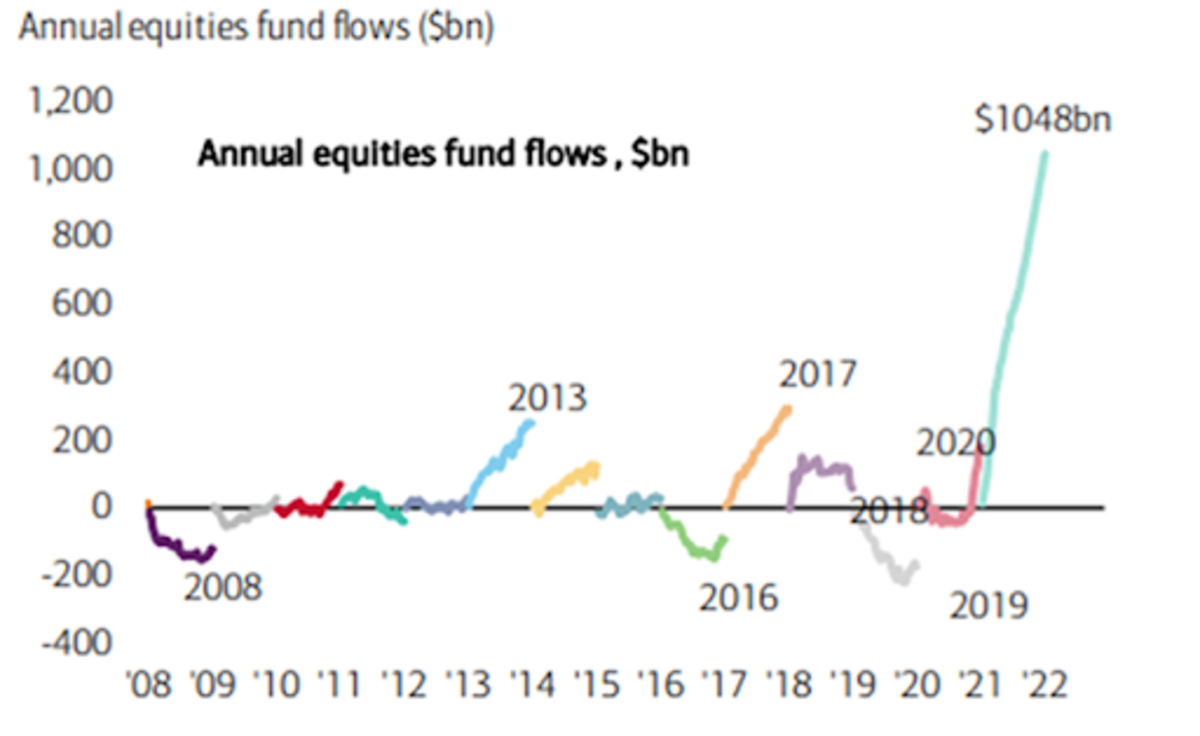

Le taux annualisé des entrées d’actions jusqu’à présent pour 2021 est d’environ 1 000 milliards de dollars. Pour certains, cela est supérieur à l’apport total cumulé en actions sur l’ensemble des 20 dernières années !

Source: Bank of America ; Michael Hartnett

Le graphique ci-dessus illustre un afflux annualisé de 1 000 milliards de dollars dans les actions en 2021, contre 800 milliards de dollars d’apports cumulés en actions de 2001 à 2020. Laissez-le pénétrer une minute avant de poursuivre cet essai. De nos jours, nous voyons tellement de graphiques, de mèmes et de statistiques insensés et sans précédent qu’il est facile de passer sous silence ce graphique. Mais cela dit vraiment quelque chose de profondément troublant sur la direction que prennent les choses.

La dette sur marge pour la négociation d’actions à effet de levier, suivie par l’Autorité de réglementation du secteur financier (FINRA), a toujours été un indicateur de l’enthousiasme et de la cupidité des investisseurs individuels (ou « de détail ») sur les marchés boursiers.

Le graphique ci-dessous représente le taux d’augmentation annuel en pourcentage de la dette sur marge, qui a historiquement anticipé les récessions, marquées par les régions en violet. Cependant, nous pouvons voir que dans la période récente, la marge a augmenté à un rythme historiquement sans précédent, atteignant peut-être un pic à court terme.

Mais l’observation clé ici est que cette augmentation rapide s’est produite après cette barre violette, plutôt qu’avant. La dette sur marge n’a pas précédé une crise mais en a été la réponse. Nous en avons vu des indices en 2009, mais c’était après une purge massive de l’endettement bancaire et immobilier, et une forte dépréciation de la valeur des actifs. La crise du COVID-19 n’a pas permis une telle purge et a mis en place des politiques pour revigorer considérablement les investissements en actions de détail. Il s’agit d’un nouveau comportement.

Source: Ed Yardeni (yardeni.com); NYSE ; FINRA; @LudiMagistR

L’allocation en actions des clients de Bank of America (BofA) Wealth Management est à un niveau record.

BofA Private private equity holdings en pourcentage des actifs sous gestion. Source: Banque d’Amérique ; Michael Hartnett

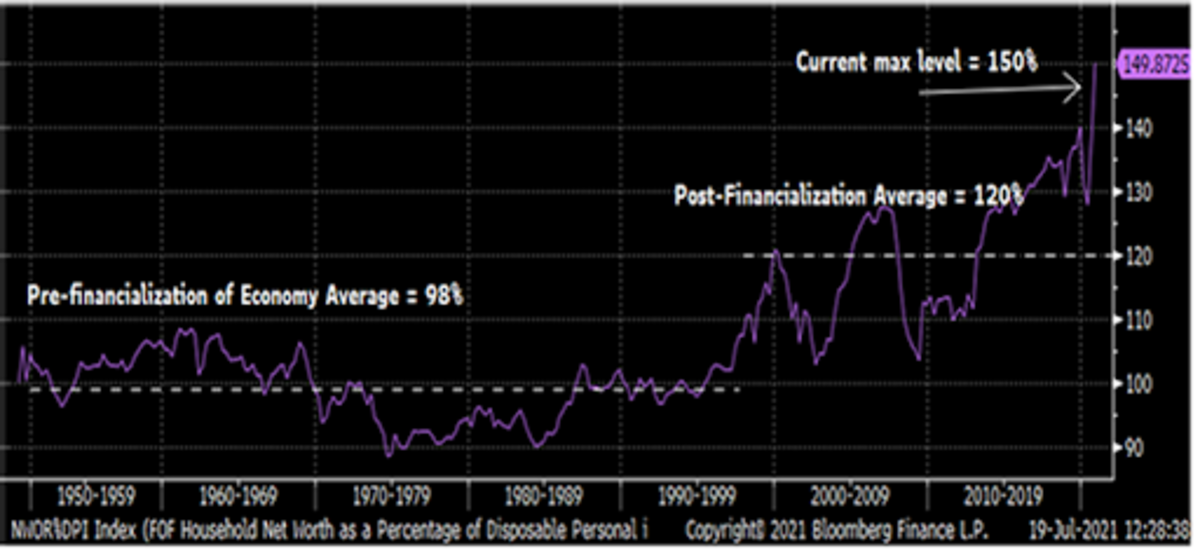

Valeur nette des ménages en pourcentage du revenu personnel disponible (violet), par rapport au ratio taux de croissance de l’épargne personnelle d’une année sur l’autre/taux de croissance de la valeur nette d’une année à l’autre (ligne blanche. Source: @LudiMagistR, Bloomberg, Réserve fédérale de St. Louis

Ce dernier graphique directement ci-dessus démontre que les individus aux États-Unis ne construisent plus d’épargne à partir de revenus excédentaires, mais à partir de l’inflation des actifs. et les actifs financiers sensibles à l’inflation sont désormais les principales réserves de valeur pour la plupart des ménages qui peuvent se permettre d’en posséder.

Pour un contexte historique plus large, vous trouverez ci-dessous la même valeur nette du ménage en pourcentage de revenu personnel disponible, remontant à 1945.

Source : @LudiMagistR, Bloomberg, Réserve fédérale de St. Louis

La mort en cas de destruction créative

Vous trouverez ci-dessous un graphique d’un indicateur connu sous le nom de quotient de Tobin, également connu sous le nom de « rapport Q ». Il s’agit essentiellement du ratio de la capitalisation actuelle du marché boursier, divisé par le coût de remplacement réel des actifs associés à ces capitaux propres.

Comme le montre le graphique ci-dessous, ce ratio est à des niveaux historiquement sans précédent. Le graphique va de l’après-guerre à aujourd’hui et exprime que les valorisations des actions sont actuellement près de deux fois et demie leur valeur de remplacement. Cela se compare à un ratio moyen sur 75 ans plus proche de la valeur de remplacement.

Certes, cette analyse n’est pas exempte de nuances, car notre économie est passée à une ère de l’information caractérisée davantage par des économies numériques, où les actifs deviennent plus immatériels et il devient donc plus difficile d’évaluer les coûts de remplacement tels que la propriété intellectuelle. et la bonne volonté des effets de réseau. Mais même si nous tenons compte de ce changement, le rapport Q actuel est toujours supérieur à trois fois la valeur de remplacement, par rapport à l’ère de l’effondrement des années 1990 avant la crise des dot-com, avec une moyenne de valeur de remplacement de 1,4 fois et un post-dot.com. moyenne de l’ère de la crise plus proche de 2,3 fois la valeur de remplacement.

Peu importe la façon dont vous découpez les données, cela démontre l’étendue des entreprises évaluées financièrement d’une manière complètement disloquée de leur réalité économique. Les sociétés dites « zombies » qui ne devraient pas exister dans un marché vraiment libre, portant souvent des quantités élevées de dettes improductives pour subvenir à leurs besoins, prospèrent dans un nouveau monde si courageux. Ces entités piègent le bon argent et le maintiennent pétrifié dans des structures en décomposition. En tant qu’investisseur professionnel qui passe beaucoup de temps à investir dans le crédit aux entreprises à haut rendement, je constate cette folie au quotidien.

À un moment donné, la seule façon de réconcilier de tels déséquilibres est soit par des restructurations massives, des faillites et des défauts de paiement, soit par l’inflation. L’inflation agit pour augmenter le dénominateur de la valeur de remplacement, dans une potion d’alchimiste de rectitude superficielle. L’inflation, comme on l’a vu tout au long de l’histoire de l’humanité, est de loin la solution la plus acceptable pour les économistes, les investisseurs de Wall Street et, bien sûr, les politiciens qui ont une vision du monde de deux à quatre ans.

Mais l’ironie de ce fait est qu’une telle prise de conscience doit également expliquer comment nous en sommes arrivés là en premier lieu.

Quotient de Tobin, 1945 à aujourd’hui : évaluation boursière par rapport à la valeur de remplacement de l’économie. Source : Le rapport Felder

Le déni de qualité

Ci-dessous, nous pouvons observer d’autres preuves d’une baisse de la qualité. Dans ce cas, nous ne parlons pas seulement de l’effondrement de la destruction créatrice et de la qualité des bilans, mais de la qualité des bénéfices globaux des entreprises elles-mêmes.

Les mesures mêmes auxquelles nous faisons confiance pour nous aider à déterminer le monde complexe des données qui nous entoure ont été manipulées et manipulées à un point où la mesure est devenue la cible. Les PCGR, ou « principes comptables généralement reconnus », est un protocole comptable conçu pour limiter la dépréciation des bénéfices par le biais de rajouts opaques, arbitraires et trompeurs. Parfois, il existe en effet des ajustements non conformes aux PCGR valides qui doivent être effectués pour obtenir une image précise du véritable potentiel de bénéfices d’une entreprise en termes de taux d’exécution. Dans l’ensemble, cependant, ces ajustements « non conformes aux PCGR » des rapports PCGR ont eu tendance à produire une image d’intégrité et de confiance moindres.

Malgré cela, nous nous sommes tellement habitués à de tels ajustements que les acteurs du marché et les régulateurs ont accepté la déviation progressive sans ciller. Il n’est peut-être pas surprenant que les ajustements non conformes aux PCGR soient d’abord « enracinés dans le tissu de l’information financière » en 1988, lorsque de nombreuses politiques de financiarisation de l’économie se sont accélérées. Il convient également de mentionner que la plupart des charges de rémunération à base d’actions sont rajoutées aux bénéfices non conformes aux PCGR. Ainsi, il y a une dynamique autoréférentielle en jeu ici, car les bénéfices non conformes aux PCGR augmentent l’apparence des bénéfices, contribuant à gonfler les valorisations boursières, qui à leur tour gonflent la rémunération à base d’actions qui contribue à gonfler les bénéfices en premier lieu. !

Le graphique ci-dessous représente l’écart entre les bénéfices non conformes aux PCGR et les bénéfices conformes aux PCGR :

Cet écart a tendance à augmenter en période de récession à mesure que les pertes hors exploitation s’accumulent. Mais il est intéressant de noter que dans les années après la récession, la tendance reprend son chemin vers une qualité plus faible.

Source : Lark Research

Bloc 2 : Un ballon à air chaud

Le résultat de cette situation est que la fragilité du système augmente rapidement, ce qui nécessite une dépendance déterministe du chemin d’accès aux données accrues manipulation, soutien gouvernemental, réglementation et intervention libre sur le marché.

Un tel contexte historique de valorisation et de performance des actifs tel qu’exposé ci-dessus signifie que l’élargissement de l’exposition aux actifs financiers à une population plus diversifiée et plus nombreuse crée un risque systémique inacceptable pour l’économie sur le long terme. Pour emprunter une expression de la théorie des jeux, le marché boursier devient un point de défaillance unique.

Comme je l’ai expliqué dans un article précédent, « Penser trop petit et les pièges du récit de l’inflation », cela devient également un moyen insidieux d’imprimer de l’argent via la création d’actifs financiers, plutôt que par le plus augmentation évidente de la masse monétaire des générations de nos parents et grands-parents. Cette incitation à gonfler par décret d’aléa moral-ou inflation des actifs financiers implicitement garantie-est encore plus facile à réaliser lorsque la technologie rend de plus en plus de produits et services moins chers ou carrément gratuits, et lorsque les contraintes d’approvisionnement comme celles que nous connaissons actuellement rendent la consommation des « trucs » physiques moins désirables, voire impossibles dans certains cas.

Les marchés de la dette correctement évalués créent des obstacles au retour sur investissement qui n’incitent que les efforts susceptibles de créer un nouveau capital productif. Une dette trop bon marché incite à tirer parti du stock de capital existant, sans besoin ni désir de gains productifs. Et même lorsque de nouveaux investissements en capital sont finalement réalisés, l’incitation claire est de le faire avec ce financement bon marché, plutôt qu’à partir de l’épargne et des flux de trésorerie. Cela conduit finalement même les répartiteurs de capital productif sur la voie d’un effet de levier excessif.

Pendant ce temps, alors que les actifs gonflent, le seul moyen de maintenir le niveau de vie souhaité consiste à déplacer toute épargne vers des actifs financiers plus risqués comme les actions, les obligations et immobilier. En effet, le retour sur investissement de la nouvelle formation de capital prend toujours plus de temps à se produire par rapport à la réexploitation du stock de capital existant lorsque l’inflation est pratiquement assurée par l’aléa moral systémique. Ajoutez à cela le fait que les taux d’intérêt opprimés et manipulés volent dans l’avenir même pour lequel de nouveaux capitaux seraient investis (voir plus loin). Cela décourage davantage tout investissement important dans un nouveau stock de capital.

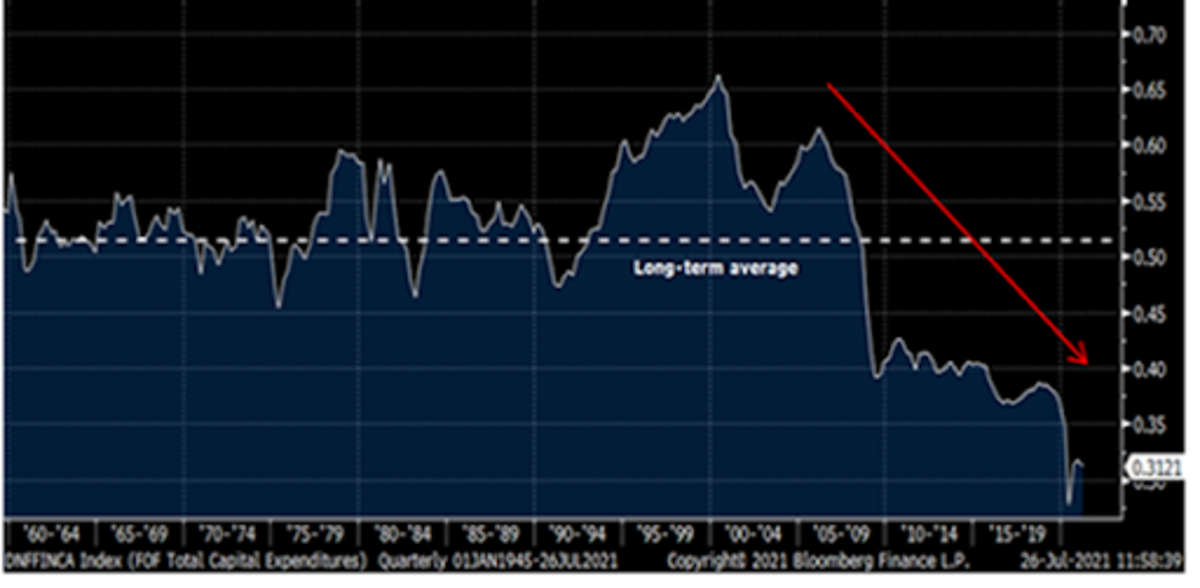

Le graphique ci-dessous présente un ratio des dépenses en capital totales des États-Unis en dollars nominaux, divisé par le dénominateur de la monnaie de base introduite dans le système, mesuré par la masse monétaire M2. Depuis le pic de la crise des dot-com, l’investissement dans la nouvelle formation de capital a chuté par rapport à la création de nouvelle monnaie. Cela soulève la question rhétorique de savoir où va tout l’excès d’argent frais, sinon vers la formation de nouveau capital. La réponse, ce sont les actifs financiers, bien sûr.

Source: Bloomberg ; @LudiMagistR

Ainsi, les incitations sont aussi claires qu’une limace raide de Stoli. Et, pendant la majeure partie des 30 dernières années, seuls les riches ont fait partie de cette conception de jeu, gagnant une place à la table avec leurs actifs existants, leur « preuve de participation.”

Cependant, il devient de plus en plus évident que l’aléa moral omniprésent, la réduction des préférences temporelles et les économies fraîchement réalisées sont les plus prochaine étape efficace dans cet arbre de décision du faux libre arbitre. Les décideurs politiques des deux côtés de l’allée sont incités à adopter un tel récit. Ils viseront à accroître la valeur nette de la classe moyenne par opposition à l’ancien livre de jeu relatif à l’amélioration des revenus de la classe moyenne, à l’éducation, aux filets de sécurité sociale et à la redistribution des impôts. Pendant ce temps, le côté droit passera volontiers le relais de l’économie monétariste du côté de l’offre, avec son « hopium » illusoire selon lequel la corporatocratie américaine partagera la richesse, et adoptera également l’inflation financière et le capitalisme socialisé. La droite percevra une telle centralisation des marchés des capitaux comme déplaisante, mais meilleure qu’une alternative au socialisme keynésien et à la redistribution. Les deux parties échangeront leurs principes fondamentaux contre une solution qui donne réellement des résultats, bien qu’à un coût énorme.

Si vous étiez un décideur politique en regardant le graphique ci-dessous, quel serait le mécanisme le moins risqué et le plus évident pour rectifier une telle divergence immense ? Facile: il suffit de lier le « salaire du travailleur typique » au S&P 500, et boum ! Mission accomplie !

Source: Institut de politique économique ; Données économiques de la Réserve fédérale (FRED)

D’accord. Supposons donc que nous ayons maintenant ouvert le bal et que nous commençons effectivement à lier l’indemnisation des travailleurs au marché boursier par divers moyens. Mais comment un tel exploit est-il accompli ? Ce n’est pas comme si le gouvernement pouvait forcer les employeurs à payer les salaires sous forme d’indices boursiers.

Eh bien, pas directement. La réponse réside dans une recette mixte d’incitations modifiées. L’aléa moral et le filet de sécurité implicite des cours des actions, tels que décrits ci-dessus, sont certainement l’épicentre d’une telle stratégie.

Mais il y en a d’innombrables autres : une épargne individuelle plus élevée d’origine fiscale avec des incitations à investir tout excès d’épargne ; les efforts de démondialisation qui encouragent les citoyens américains à investir et à épargner davantage au niveau national plutôt que les importations de consommation en provenance de Chine ; et la progression naturelle de la technologie et de l’innovation financière simplement «faire leur truc», créant de plus grandes rampes d’accès pour l’investissement démocratisé-des exemples seraient des produits tels que les fonds négociés en bourse (ETF), les plateformes de trading comme Robin Hood qui simplifient l’utilisateur l’expérience, les blogs alimentés par les médias sociaux, les chaînes YouTube et les plateformes d’infodivertissement alternatives qui renforcent la confiance, puis saupoudrent ce bouillon d’une bonne dose de FOMO au niveau culturel. Un autre mécanisme évident consisterait à augmenter les impôts sur le revenu pour détourner l’argent vers des investissements financiers et à augmenter les impôts sur les gains en capital pour inciter le comportement de HODLing sur le marché boursier. Ce ne sont que des exemples. Le point ici est qu’il existe une boîte à outils illimitée disponible pour atteindre ces objectifs, à la fois intentionnellement et organiquement par le biais des incitations naturelles du système.

« Mais attendez », dites-vous. « Qu’est-ce qui ne va pas avec un taux d’épargne plus élevé et une consommation moindre ? Après tout, n’est-ce pas un principe fondamental de nombreux Bitcoiners ?”

Le problème est que même avant un tel changement de carrière sociétal comme celui auquel nous assistons aujourd’hui, le niveau des prix des actifs par rapport à leur valeur fondamentale avait déjà franchi un point de non-retour, créant un sentiment de fatalisme frustrant pour de nombreux acteurs du marché aux yeux ouverts.

Des décennies de baisse des taux d’actualisation ont déjà volé tellement de valeur à l’avenir qu’il n’y a plus de futurs semis de croissance à même de prendre racine. Ainsi, le problème ici n’est pas l’épargne en soi, mais les pâturages d’épargne spécifiques dans lesquels les individus sont parqués. L’épargne n’est pas l’épargne si elle n’est pas canalisée vers de véritables réserves de valeur. Tout le contraire en fait. Le seul moyen de maintenir le niveau de vie actuel nécessite des taux de croissance perpétuels des prix des actifs, qui à leur tour nécessitent de plus en plus de dettes.

Si le gouvernement et les influenceurs culturels normatifs devaient exporter une telle dynamique vers les masses, quel devrait être le résultat ? Est-ce une égalité et une abondance utopiques ? Ou est-ce une planification centrale, un marché libre marginalisé et une activité économique socialisée ? Tu l’as deviné! Porte numéro deux, Bob !

Source : Business Insider, CBS

Bloc 3 : mathématiques

L’une des variables les plus influentes qui a historiquement été associée à la fin de périodes de grande stabilité et de force a été l’inégalité des richesses. Bien qu’une telle asymétrie soit rarement à l’origine d’un effondrement systémique, elle est presque toujours un symptôme de la dégradation et joue tout aussi souvent un rôle dans la catalyse du point de basculement vers le déclin. Des Mayas à l’Empire romain aux Trois Royaumes chinois aux Ottomans aux révolutions française, russe et chinoise, l’inégalité des richesses a toujours joué un rôle majeur.

Source : Ray Dalio,”The Changing World Order,”Chapter One

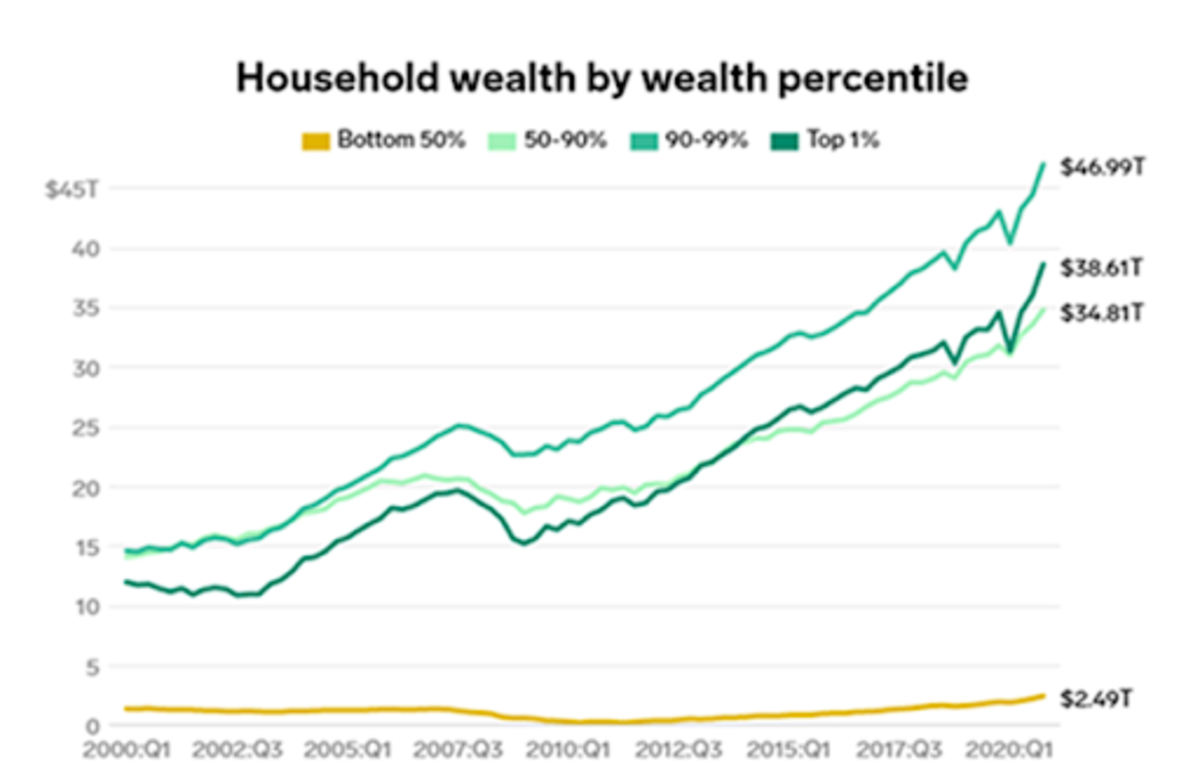

C’est un gros problème pour la stratégie de classe d’investisseurs de masse. This is because a goal of wealth redistribution with a strategy centered around asset inflation is statistically impossible to achieve.

Many proponents of this new investor class take the “fight fire with fire” approach. Yes, asset inflation — driven by modern monetary policy — has been the prevailing impulse of inequality over the last several decades. Why should the average individual not be able to get their just desserts as well? Ethically speaking, I take no issue with such retribution to some degree.

Unfortunately, it’s an illusion. The presiding growth curve that has been empirically witnessed as it pertains to wealth distribution has been found in the Pareto principle, a probability distribution whereby a small percentage of the sample group acquires most of the attainable value. Facets of this law, more colloquially known as the “80/20 rule,” are observed not just in wealth distribution, but prolifically throughout much of nature and human social environments.

We have experienced at least a half-century of Cantillon effects that have supported asset owners in exponentially outperforming relative to income owners. Even if we disposed entirely of such Cantillon effects and allowed the broader population equal access to financial assets going forward, and even if financial assets continued to generate historically anomalous returns, the “80 percenters” would never catch up. The reason for this is simply due to the nature of exponential growth curves as seen in the Pareto principle. Inequality would be maintained at the very least, if not continue its asymptotic expansion.

Pareto’s law: How asset inflation becomes a highly entropic state for wealth distribution, regardless of policy.

Source: DeanYeong.com

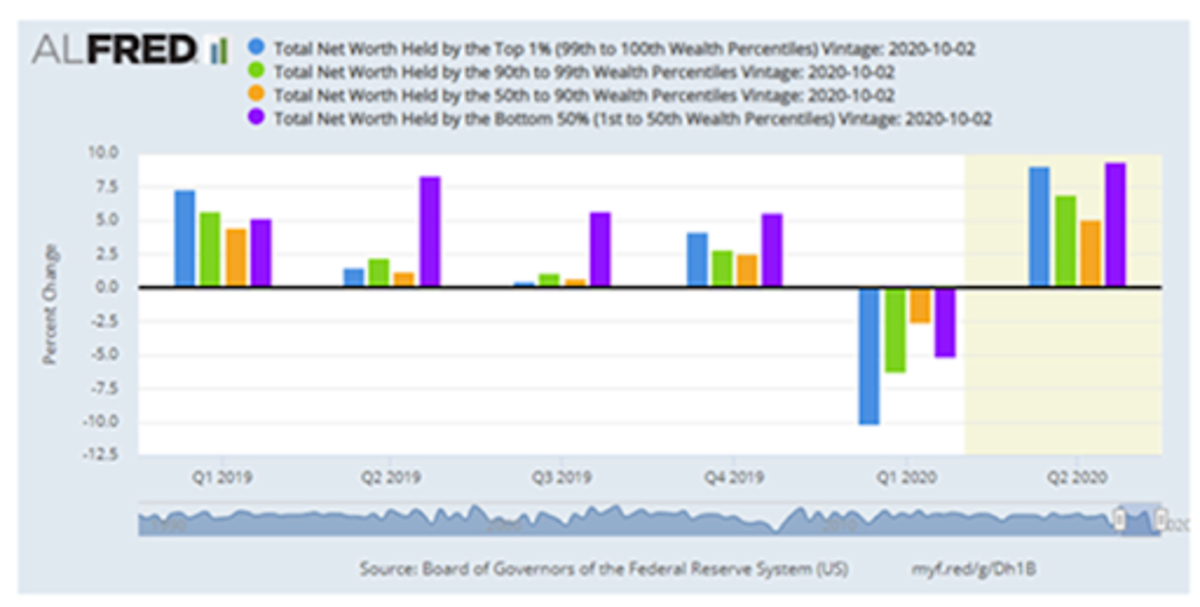

This Pareto probability distribution is exemplified quite dramatically after looking at 2020 as an outlier year, whereby the least wealthy percentiles actually saw the largest percentage improvement in wealth. However, while this is a lovely-sounding statistic for social media hype and political propaganda, it is purely a mathematical outlier caused by starting from such a low base and from such a low level of prior financial asset ownership.

Unfortunately, the banner year for the bottom 50% (purple bar below), did next to nothing to narrow the wealth gap from the top percentiles, as evidenced by the below chart.

Source: Federal Reserve

2020 did nothing to rectify the problems of inequality. In fact, inequality only got worse. Why would a continuation of asset inflation look any different in the future?

Source: Federal Reserve, “Distributional Financial Accounts”

If inequality cannot be corrected by the only policy tools available, the risks for social instability will only rise further. Ironically, when stability is threatened, this tends to only increase levels of centralization.

Have you ever been driving your car on a wet, slippery road, only to fish-tale unexpectedly? While our instinctual response would be to tense up and violently steer the wheel in the opposite direction to regain control, such a reaction would only worsen our dire predicament. One must steer into the chaos. Once control has gone, such a fate must be embraced, not opposed. This is the only way out. Further attempts at control only make matters worse.

Block Four: All Roads Lead To One Road, More Centralization

Once the inevitability of blocks one, two and three as stated above are appreciated, the path dependency of block four in our chain becomes absurdly apparent: Subsidizing asset prices through monetary debasement becomes the oblique way that society yields to ideologies like universal basic income (UBI).

UBI may end up in the very long run as explicit social welfare programs, or “helicopter money.” Of course, during COVID-19, we saw some discreet examples of this, turning something merely theoretical into a tangible part of the societal zeitgeist. However, it is a mistake to assume a linear path, that such policy will now settle as the initial and most effective vector for such policy going forward.

A more frictionless pathway would be the mechanism outlined above, whereby social welfare can be extolled circuitously. The brilliance of such a policy approach is that it would not require any incremental pieces of legislation, and no constitutional alterations to property rights. There are no foundational legal constraints. This implies that our current institutions have the power to accomplish such social welfare goals today.

One could argue that some changes would certainly make these aims easier to administer, like augmenting the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 and expanding the powers of the U.S. Treasury Department. However, the key point here is that such change is not required. If the reader finds this too far fetched, I would recommend listening to the taped conversations between ex-President Richard Nixon, and then-Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns. It has happened before in this country, and in less dire circumstances.

Source: TheHill.com

UBI advocates are here, and they have their own network effects:

“The map references not only networks with the sole purpose of advocating UBI, but also all organizations (networks, foundations, platforms, political parties, working groups within political parties, societies, study groups, etc.) that advocate for UBI.” Source.

American openness toward socialism, and a commensurate disdain for capitalist ideals, has increased dramatically over the last four generations. This has been well documented with recent generations, particularly millennials, but it is important to recall that such a trend has been consistent well before that, even with the boomer generation relative to their parents and grandparents.

This is rather alarming when one considers that this generation has been the biggest beneficiary of financial asset prices (coincident with the full embrace of the fiat monetary system) of any generation in American history.

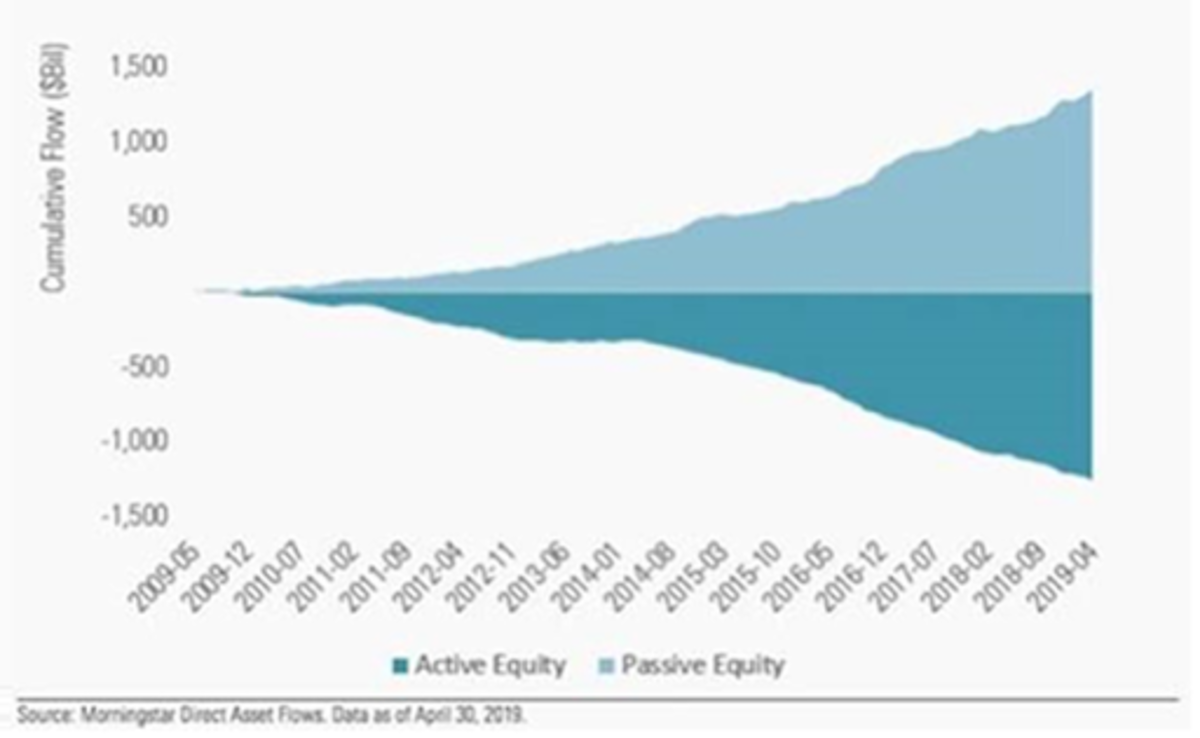

A Quick, “Passifict” Detour: Passive Investing Socializes Capitalism

Bitcoin may be humanity’s historically most perfect manifestation of a pacifist revolution, but passive investing is also a revolution, only with completely opposite implications.

Historical analogues are always dangerous, and each generational crossroads exhibit unique characteristics that can change the entire spectrum of outcomes. However, as a reference point, current trends reverberate with echoes of previous centralizing efforts designed to redirect our collective future and shift the public behavior, reminiscent of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “new deal,” as well as Nixon’s “great society,” or even going back to German Chancellor Bismarck and his social welfare policies in the 1880s, which greatly enhanced the Second Reich’s military capacity.

Passive or indexed investing vehicles such as exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are yet another example of this shift toward a “mass investor class.” While such a trend may seem innocuous, it is cultivating the seeds of enormous societal change.

As discussed by Inigo Fraser-Jenkins, a highly-regarded maverick quantitative equity strategist at Wall Street firm Bernstein, passive investing can be compared to Marxism. This may sound hyperbolic, but unfortunately, I believe he is on to something important here, the point being that the democratization of capital markets by way of ETF proliferation and other passive investing products inadvertently leads to a socialization of capital.

It would all but complete our societal transgression from liberal democracy to social democracy, a trend that has been gradually underway, but accelerating over the past 75 years. Fraser-Jenkins compared passive investing to other societal externalities like the tragedy of the commons, whereby behavior that may be optimal for the individual investor can be quite negative for the aggregate society when all actors behave the same way (we will return to the problem of the commons later).

The unfettered expansion of passive investing does not look likely to subside any time soon. This is especially obvious when one simply looks at the below chart, or even at the hiring behavior on Capitol Hill, like the large representation of Blackrock alumni acquiring key roles in the current White House administration. Blackrock is the number-one manufacturer of passive investment vehicles in the world, with over $1.8 trillion in assets under management (followed by Vanguard in second place at $1.2 trillion).

Additionally, ESG and clean energy investment mandates further this shift, creating new products to bundle into thematic passive investment securities. Such bundles make it easier for ESG-approved companies to redirect capital away from those companies that do not fit the homogenous definitions prescribed. To be clear, there is nothing intrinsically bad about incentivizing cleaner energy and more sustainable economic practices. Of course, this is a good thing! However, when rules for such behavior become formalized, complex, and sometimes arbitrary and naively general, they impinge upon the competitive dynamics of free markets that would accomplish such goals more effectively.

Instead, such rules generalize the flow of investment, compensating those market participants best suited to game such a system. The new game defines the winners as those best able to adhere to the appropriate definitions as a means of acquiring low-cost capital. In a road paved with good intentions, we potentially end up in hell, robbing free markets of innovation, nuance, and differentiation. We write new rules of the game, rules that thoughtlessly increase centralization.

Mike Green, a distinguished researcher of passive investment stated back in 2020:

“Of managed assets, [passive investment] is now greater than 50% [and over 40% of total market capitalization]. That split though, is not uniform across demographics. Millennials are almost 95% passive. Boomers are only 20% passive. For the vast majority of millennials, their only exposure to the market… We make a lot of hype about things like Robin Hood and stuff, but the actual assets are tiny. The vast majority of the money that they’re getting is actually just going into things like Vanguard target-date funds.”

Active equity managers have seen outflows every year and passive investment vehicles have seen inflows every single year since 2006. And this trend is only accelerating:

Source: Morningstar

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Bank of America’s private client ETF holdings as percentage of assets under management (AUM). A hard trend to fight:

Source: Bank of America, Michael Hartnett

The passive singularity: Millennials have 95% of their retirement savings invested in passive vehicles. What is the logical conclusion of this freight train?

“One of the challenges that gets created as passive becomes a larger and larger share is that there becomes no discretion. There is no consideration of should the incremental dollar go in in the exact same fashion, right? That passive player has no instruction to sell. You exhibit increased inelasticity in terms of each incremental dollar that goes in. Imagine a scenario in which 100% of the owners of a company were passive and you tried to buy a share. There is no price at which they would be willing to sell to you unless they received an instruction from their end investors saying to sell shares to you. Prices could theoretically become infinite on that type of dynamic. Eventually, you would expect somebody to respond by saying, ‘All right, I will sell an additional share to you.’ Traditionally, that’s been accomplished by price-sensitive or return-sensitive discretionary managers who say, “Okay, this price is unwarranted by the fundamentals. Therefore, I’m willing to sell some of these shares to this person who’s expressing, in my view, an irrational demand for these shares.” If that demand is so strong and it gets absolutely extreme, people can synthetically create shares by shorting, but that is incredibly dangerous to do, an environment in which stocks are exhibiting this reduced elasticity.” –Green

The mass investor class faces a big incentive problem: What does the internet, digital property, and a tragedy of the commons have in common? Our retirement accounts.

The dismantled connection of choice from the capital allocation process brought about by passive investment proliferation has implications beyond the clear destruction of price signals. This is no small statement. A destruction of price signaling is as destructive as things can get for a capitalist system. Prices are the main form of communication we use in society to make appropriate economic decisions and choices. Its dissolution is of existential importance.

However, there are other problems to consider from this evolution of behavior as well. Ever since the runup to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, and at an accelerating pace since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, society has become more aware of the vast concentration of power that the internet giants and social media platforms carry.

Pockets of government and pockets of new and growing cultural progressive movements have quite easily influenced and incentivized these platforms to actively censor speech in our democracy. This is not a political statement, and this is not a judgement about the people being censored, but merely a factual observation about a key tenant of our democratic institutions. If the U.S. Constitution can be likened to the “core protocol algorithm” dictating the manner in which our collective network operates, this is a clear attack on one of the most vital rules of the protocol. How can we so readily dilute our core principals?

First, network effects are powerful. The ability of the internet companies to sustain and grow off individual resources, with extremely low detachment rates, cannot be underestimated.

How did this come to be? A failure in timing. As is often the case with disruptive technology, its usage preceded an appropriate infrastructure to handle it. Unfortunately, the Byzantine Generals Problem was not solved before the advent of the internet. Consequently, we have been suffering the consequences that a lack of enforceable property rights leads to in a digital world. A winner takes all society.

This is what the internet got wrong. You didn’t own anything. No one had any stake on the internet. Instead, value has been extracted by those who figured out ways to own the on-ramps and access points to the internet instead.

This group has become the “landlord class” of the internet, and the vast majority of value proffered by the internet and its myriad innovations of social communication has been funneled through this layer. The consequence, of course, has been more inequality, more surveillance and control, and more concentration of power. Further, we’ve witnessed a trend toward a reduction of quality of information. There is a diffusion of responsibility that engulfs the internet when ownership is so opaque and ephemeral. We are incentivized to create more noise than signal because when no one owns the land, there is no incentive to be a steward of that land to ensure its long-term sustainability, utility and productivity. Instead, the incentives align so as to be solely transactional. The more information one can manage, control and recapitulate, the more one can develop network effects and externalize the social and economic cost of a system that produces excessive noise and underproduces enough structured signals that could offer synergistic benefits across societal planes. That cost is shared by all of society. It’s a tragedy of the commons. All because the internet couldn’t address digital property rights.

The second issue here is that network effects also impact passive investing. Most passive vehicles are ETFs, that are indexed and weighted by market capitalization. The bigger you are, the more capital you attract. Size matters, aptitude and productivity do not. This takes us back to the Pareto principle and the 80/20 rule, setting the stage for increasingly non-linear distributions of capital. And in a world where access to low-cost capital is a massive competitive advantage, we end up with an obvious outcome. The big continually get bigger, and the small get only smaller. Or worse, the upstart disruptors may never have a chance, and we would never even know what could have been.

That brings us to the present, where just six behemoths have a near majority control of the entire equity market. Most investors do not blink at this statistic any longer. Professional investors have been numbed to such lopsidedness. However, imagine if such inequality persisted within the domain of political parties? In democratic institutions? In your childrens’ classrooms? But the real question we need to start seriously and honestly asking ourselves is this:

If the below chart only becomes even more extreme in its weighting distribution, and if our collective wealth is increasingly tied to the index it represents, what will our incentives be as the companies involved become even more centralized?

About 45% to 50% of our savings are tied to companies that could be actively censoring us, and indirectly eroding the very principles of the system that allowed them to prosper. This share of our savings will only grow further. Will we object? I certainly hope so. But so far, there is little evidence to support that aspiration. Unfortunately, passive investing, alongside a mass investor class, is likely to only help internet platforms and capital markets centralize further.

Major stock indices are mainly just six names now: Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft and Nvidia, totaling 42% of the equity market.

Source: Wolfe Research

Block Five: All Roads Lead To Zero

What happens when zero volatility is the new equilibrium?

After our modest digression into passive investing, let us now return to the last block in our chain. The final and most deadly flaw in the chain reaction socializing financial assets relates to volatility and the cost of capital. Mathematically speaking, publicly-administered financial markets that demand continuous appreciation, distributed broadly and without diversification, will require volatility to trend toward zero over time.

A simple law in financial markets, when assessing an asset’s volatility (as measured by its standard deviation of returns over a given period), is that the more vulnerable to uncertainty an asset is, the less it can absorb volatility. This is why, for example, equity investors are generally willing to pay lower valuation multiples for cyclical or economically-sensitive sectors relative to secular growth or defensive industries. These types of companies are more vulnerable to unforeseen events. When our financial markets are a tool of policy rather than an expression of free market capital allocation, we eventually become incapable of withstanding any uncertainty. And manipulation to affect policy outcomes would be the only way to ensure uncertainty’s suppression. If successfully orchestrated, volatility must eventually collapse toward a zero bound to accommodate this.

As our centralized debt trap expands in circumference, the risk-free rate must also trend toward zero, as has been the case over the past 40 years. Over time, the consequence of this could even be the elimination of the need for a private sector.

This last section is essential to our thesis, as it is the bridge that transports us from the current transitional sandwich era where we find ourselves juxtaposed between centralization and decentralization. This is the last stop on this transitional train as we push relentlessly down the path toward a more authoritarian world order. Given its level of importance in our story, it requires some more detailed explanation.

Centralization As A Black Hole: The Volatility Singularity

Source: Disney, Pixar

What is the volatility singularity? Previously, we have established the logical chain of cascading events that are required in our world’s existing model.

Debt must go up, so stocks must go up. Thus, rates must go down, so volatility must go down. When this happens debt will logically go up, leveraging the system even more, so stocks must go up to prevent collapse and inflate the debt bubble with a greater equity cushion… (stop for breath)… So, rates must go down again until zero, so volatility must go down until zero.

Volatility collides with zero. Everything goes to infinity. Yippie! The transcendent state where the difference between nothing and everything gets very fuzzy and rather philosophically confusing. Just as observed in the case of black holes, where physics starts to behave mysteriously and spooky as one approaches the event horizon, so too do economies. Things start to get pretty eerie as we approach the zero point event horizon in volatility.

Thinking about the problem in the following simplified manner may be helpful:

Anything divided by zero equals infinity. Financial assets returns are a function of volatility. A common formula used to calculate risk-adjusted returns is called the Sharpe ratio, which is an asset’s return during a given period, minus a market risk-free rate, divided by the investment’s standard deviation of returns. If volatility is, for all intents and purposes, equal to zero, so too is its standard deviation. Thus, we end up in a confounding situation in which excess returns are divided by nothing, and therefore magically become, well… everything.

Image source. Source of quote: Kurt Vonnegut, “Slaughterhouse-Five”

As macro volatility fund manager Christopher Cole excellently laid out in a 2020 piece titled “The Allegory Of the Hawk And The Serpent,” an investment strategy designed to short volatility, or benefit when it decreases, experienced temporally anomalous returns since the early 1980s, right when the financialization of Wall Street took off exponentially, and right as Alan Greenspan et al. began a campaign of moral hazard, at a time known as “The Greenspan Put.”

The stock market and nearly all financial assets in aggregate then become just a mere proxy for this “short volatility” expression.

Source: Artemis Capital, @vol_christopher

An Endangered Golden Goose

Cole, like many others, believes this period of declining volatility is mean reverting and must therefore repeal its nearly 40-year journey. While certainly possible over a cyclical short term time horizon given the magnitude of the move, a spike in volatility is unlikely to be palatable for any sustained period. The reason, as you might have guessed, is because of the deterministic nature of acceptable outcomes laid out above. The violence to the system that a spike in volatility would require would eviscerate so much wealth, so many debt obligations, that the policy response would be equally violent. Such a response is all but guaranteed because the crisis would be existential for those in power.

This outcome becomes more assured each day that goes by with greater reliance on financial assets to lift us into the future, each day that a citizen puts their first dollar of savings into such a system, and each day that another dollar is diverted away from new capital expenditure in favor of being recycled instead back into the existing sinkhole.

Below is a graph of the realized one-year volatility in the Dow Jones Industrial Index going all the way back to 1895. The pre-WWII average of this proxy for stock market volatility was about 20%, witnessing only one to two “black swan” spikes during a 50-year span. Meanwhile, the post-WWII average has been closer to 14.5%, with three black swan events observed only within a 30-year period!

This graph gives us two important pieces of information:

Volatility is trending lower over time. A move from 20% to 14.5% may not sound significant, but this is a nearly 30% decline in average volatility. The positive effect of such a shift has on underlying asset prices cannot be overstated. A system of declining volatility has come at the heavy cost of greater susceptibility to bouts of near-disastrous black swan events, external and internal shocks. And these events are not capable of being permitted to clear the imbalances that caused them, to self correct, as the system would break before such catharsis could be attained. Instead, each successive crisis forces policymakers to intervene at much lower levels of volatility than in the pre-WWII era. This of course fuels greater abdication of responsibility, which fuels the next crisis as we rinse and repeat, racing toward zero.

Source: @LudiMagistR, Bloomberg

Centralization Is A Fabergé Egg: Systems Which Require Stability And Efficiency Are Always Extremely Fragile

I recently came across a white paper authored by Ben Inker and Jeremy Grantham, famed hedge fund investors at GMO. They conducted a data mining project and looked at the prior periods of frothy financial markets like the 1999 to 2000 period, and similar historic periods of strong performance and excess returns. They were surprised to find that it wasn’t earnings growth, the level of real interest rates, or even GDP growth that mattered during such periods of excess and euphoria.

Instead, they found three consistent variables that were always part of the equation:

Atypically high profitability for one or some segments of the economy (this is finance speak for maximal efficiency rather than maximal productivity)The stability of GDP (as a proxy for overall economic activity)The stability of the rate of inflation

In short, markets care not about actual levels of growth, inflation and profits. Predictability is what matters. A financialized system and a mass investor class requires stability and loathes uncertainty. Said differently, our system of monetary inflation rewards monopoly formation, values efficiency over productivity, and requires reduced volatility to sustain itself.

Given that volatility is a natural phenomenon of any free system, suppressing it requires external and artificial forces. It requires a central authority to manage the system and to solve for low volatility. Our central bank policy of monetizing moral hazard is evidence of this. Moral hazard from this prism is simply a function that solves for low volatility, at all costs. And there are a lot of costs.

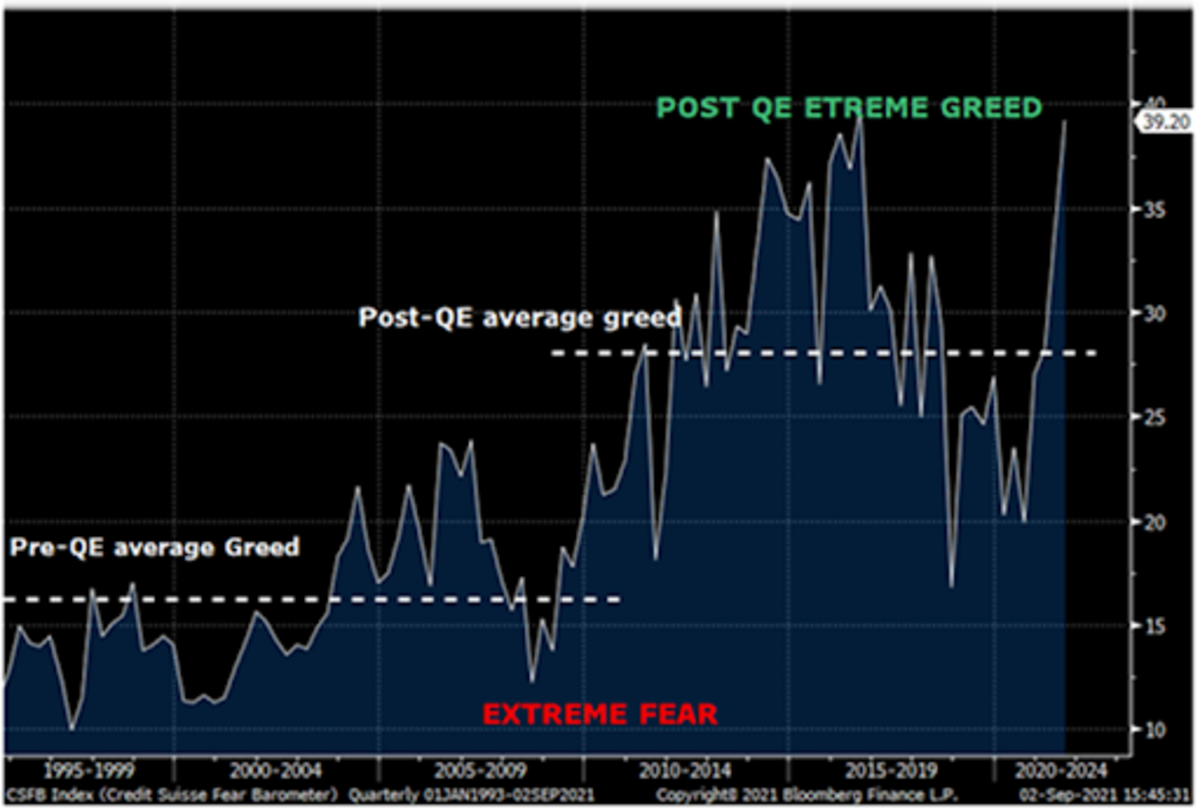

Moral hazard visualized: Credit Suisse Fear And Greed Index. Source: @LudiMagistR; Bloomberg; Credit Suisse

The Difference Between A Medicine And A Poison Often Comes Down To Dosage

While the importance of gains in efficiency are indeed a requisite aspect of technological progress as well as a tremendous generator of wealth for those providing such efficiency gains, there is always a trade off. A great example of this is the Bitcoin block size war of 2017, as well as the many utility protocols proliferating the crypto universe, optimizing for network throughput at the cost of much weaker decentralization. The irony is that the many use cases of blockchains become completely obsoleted without decentralization. Efficiency is great. It’s exciting. It often is associated with innovation. To a point.

Where is this point?

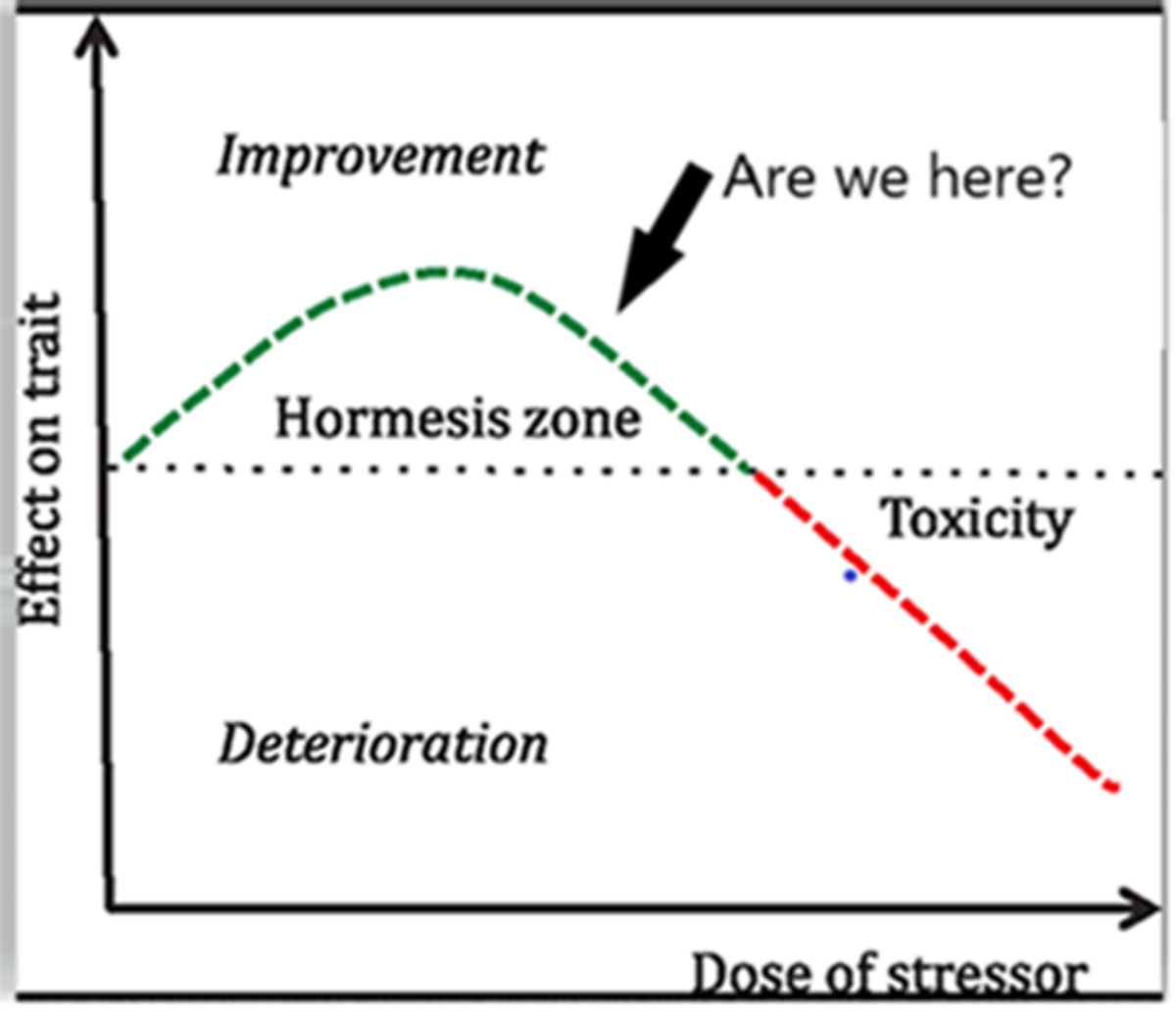

Any marginal gain in efficiency requires a marginal loss of resilience. Given that resilience is vague and incandescent, a decline can seem harmless until it suddenly breaks completely. This means that the relationship between efficiency and resilience is non-linear. There is always a point on the curve where the benefit of efficiency gains become precipitously overwhelmed by the cumulative trade-offs.

Source: Nassim Taleb, “Antifragile”; @LudiMagistR

Ok, fine. Let’s agree that the financial system is in fact becoming more fragile. What does this have to do with centralization of power? Shouldn’t a fragile system lead to the dissolution of power?

Short answer? No.

Less short answer? A centralizing power depends on vulnerability to validate its own existence. As the costs of centralization mount, is becomes existentially vital for an authority to lay claim on the sole ability to medicate the very ailments it fabricates, so as to traverse unstable times unscathed. Fragility maintains power. Power thrives on fragility.

Efficiency Is A Great Barometer Of Where We Are In The Macro Cycle

Why? Efficiency naturally peaks at the end of a regime. By the end of the regime, everyone assumes the cycle to be permanent because no one remembers a different world. We succumb to recency bias, forget history, and inadequately discount the inevitability of change.

Efficiency, fundamentally, is a way of optimizing processes or work to a specific environment. By the end of a regime’s lifespan, an environment’s self-selected economic participants have naturally maxed out adaptations to that one environment, having gone “all in” on its defining characteristics.

Thus, like a grain of sand placed on a growing sandpile, all that is needed is just one inopportune shift and the whole system cascades down with surprising fragility. A meteor hits, and we are cold-blooded, energy-consuming goliaths. Bonne chance avec ça!

We’ve of course seen this story time and time again throughout history, both at biological and evolutionary scales when diversity is overcome by uniform specialization, and throughout the annals of human history. This is one explanation as to why empires always eventually fall. Their successes eventually become their weaknesses. Efficiency helps fuel dominance in a world that values power as a function of resources, but it leads to dangerous deficits in resiliency that inevitably make them easy to destroy. This is also why empires are often built over long periods of gradual ascent, but often fall precipitously. Non-linearity.

Thus, somewhat counterintuitively perhaps, periods of maximal efficiency will precede periods of instability and upheaval.

An Obituary For The Private Sector

Now, let us return to volatility.

As the boulder of zero volatility and a fully-managed economy slides precipitously toward its Newtonian fate, there will slowly materialize some incredibly powerful implications for the structure of private property rights. This is because zero volatility and a required real risk-free interest rate held at zero or negative levels will logically push the aggregate cost of capital to extremes.

When there is no risk of material loss for capital, there becomes no discrimination as to how to invest it. The decision-making process becomes tied much more to government policy goals, cronyism and bribery, and other characteristics very similar to those of communist systems of governance. The corporation and the entrepreneur lose their utility in this world.

The birth of the modern corporation can be traced back at least to Adam Smith’s 1776 classic, “Wealth Of Nations,” interestingly published the same year that colonists here in America sought independence.

In this work, he lashed out at the “business association,” his era’s version of the state-owned companies, or the precursor of the “military-industrial” complex, or in China’s case the Sovereign-Owned Enterprise (SOE). These were institutions like the British and Dutch East India companies in Smith’s time.

He argued against monopolist business practices, which in turn paved the way for the legal autonomy of business outside the direct control of the government. As far back as 1844, corporations began earning the status of “personhood,” eventually granting them 14th Amendment rights in 1886. This paved the way for the evolution of corporate oversight toward the domain of the court system and not that of the executive and legislative branches.

The point here is that while we sometimes think of corporations as gatekeepers, monopolists, greedy beneficiaries of consumerism, debt and inflationary growth, these adjectives describe their failures within our current system, not their original purpose. The corporation was originally designed to bestow greater power to the entrepreneur and decentralize power away from the state.

By providing legal protections like limited liability, the corporate structure allowed for individuals to combine resources without unmanageable personal risk, which in turn allowed for the competitive acquisition of capital for investment. So, when the cost of capital and the risk of capital become immaterial, the existential purpose for the corporation becomes difficult to justify. And so the economy centralizes further with the erosion of one more source of decentralization.

What is so exciting about Bitcoin within this context is that it replaces the vacuum created from an impotent corporate private market structure with something much more decentralized and much better suited for the evolving digital information economy. It helps an increasingly interconnected economy divide labor beyond its current stalemate.

Bitcoin is a medium of specialization. Corporations were invented to be a specializing spoke of private capital, allowing for greater and more scalable division of labor. Unfortunately, in a world where the digital realm is becoming the majority sphere of economic activity, where individual property rights had not been assured prior to Bitcoin, the corporation instead has more often become a rent seeker, a bottleneck for competition, and a gatekeeper of digital property. This has had the perverse effect of decreasing our collective ability to specialize. Bitcoin solves this problem.

However, I am getting ahead of myself. We will get into this exciting potential in greater detail in part two of this series.

A Dangerous Cocktail: Why The Pareto Principle Matters

As the world becomes more interconnected, relationships become more “Paretian,” and less “normal,” or mean reverting. This is because the Pareto principle has shown empirically that complex systems often demonstrate extremely asymmetrical distributions of effect. Effects that only magnify as the system grows larger.

Prior to the interconnectedness driven by technologies and the scalability of digital networks, such Pareto effects were only discernible at ultra-large scales or where the complexity of the system was much larger than witnessed in everyday life, in fields such as macroeconomics, astronomy, geology, ecology and theoretical physics. But over time it is being appreciated just how pervasive this Pareto dynamic truly is.

In the business world, it has been shown that roughly 20% of customers often produce 80% of a company’s revenue. Eighty percent of a company’s output, likewise, is often generated by 20% of its employees. The pattern is found in many random systems. Eighty percent of highway accidents occur at 20% of the path traveled (near home), 80% of the cost of building is spent on 20% of the structure, and 20% of the world population is responsible for 80% of the pollution. The list could go on. But this simplified 80/20 rule actually understates the impact, as it is simply an approximate guide, the map rather than the road itself.

In fact, this 80/20 ratio can often turn into 99.9999/.0001 quite easily. Take a simple example where the square root of the total nodes in a given network is the number of nodes that are deemed to have the most measurable impact on that network. If we start with 10 nodes, we have about three nodes fulfilling that role, or about 30%. If the network grows to 500 nodes, we get about 22 nodes, or less than 5% of the network. If we end up with 500,000 nodes on the network, the figure would be about 707 nodes providing that impact, or a stunningly small fraction of 0.1%. Non-uniformity scales exquisitely.

As we begin to see, the Pareto principle is powerful in large systems, and is so important today as the world interconnects exponentially and in increasingly fractal patterns. The bigger the network, the more extreme the variance. Decentralization is a natural outcome of network building, especially if allowed to flourish without interference or external exploitation. Therefore, it is a logical conclusion as a general principle that decentralization increases variance and begins to break down previous patterns of mean reversion that are so characteristic of normal probability distributions.

Conversely, centralization craves more uniformity. Otherwise, there become too many outliers in the herd to corral, and the system becomes unmanageable. As networks proliferate, governments increasingly are driven existentially to ramp up the use of power and coercion against this natural force.

Not only is the world experiencing greater dispersion of outcomes, it is also changing at an increasingly faster pace. Raw data is pouring torrentially down upon us, overwhelming our neural capacity more each day. We are confused, overwhelmed and looking for anchors, answers, and authority.

“Black swan” or “tail risk” events, by definition, are not predictable by any model. Otherwise, they would not be black swans. Models often give us a false sense of stability, understanding, and confidence. The renowned behavioral economist Daniel Kanneman has shown that even when we are given statistical predictions that we know to be spurious, we embarrassingly cannot help but feel assured and make more risky decisions based on such irrelevant data.

Nonetheless, the pace of change and data dumping has inspired us to overly romanticize and revere data accumulation, prediction, and data modeling techniques. We even have new professions that have popped up to deal with such issues, often aptly referred to as data “scientists.” Most major universities over the past decade have added degree programs for data science and it is now one the fastest-growing programs in academia.

Source: Michael Rappa, Institute for Advanced Analytics, May 2021

Now, let us more holistically recapitulate the situation described above. The cacophony of noise is getting ever louder, and meanwhile, our ability to filter this data to uncover the important signals hiding within has not improved at all.

We have developed technological tools that can filter the raw data and improve its informational extractability. However, these improvements are limited solely to endeavors that we are comfortable deferring to computers to manage for us. In all activities where humans still require involvement or apprehension, we are completely outmatched. On top of this, technology can be a tool, but it can also be a weapon. For every search, storage and AI tool that has helped to unbundle the noise into some semblance of a signal, there are other software tools that re-bundle the signal once again back into noise. Particularly social media, mainstream media, political propaganda and social science professions that overconfidently apply the newfound data abundance.

Taking all of these themes together, we have rampant technological shifts, overwhelming data propagation, and overconfident and confused human actors trying to adapt to these self-inflicted changes to achieve the unattainable: control. This means an increasing risk of the black swan events we so fiercely aim to circumvent. Less predictability, and more hubris as to our collective capacity to pattern-recognize and avoid those rare and historically pivotal events. This is a very dangerous cocktail.

An Homage To Endurance, Tenacity And Immutability

“I think much more likely is an even worse alternative: government will not cease inflating, but will, as it has been doing, try to suppress the open effects of this inflation. It will be driven by continual inflation into price controls, into increasing direction of the whole economic system. It is therefore now not merely a question of giving us better money, under which the market system will function infinitely better than it has ever done before… but of warding off the gradual decline into a totalitarian, planned system, which will, at least in this country, not come because anybody wants to introduce it, but will come step by step in an effort to suppress the effects of the inflation which is going on.” –Friedrich A. Hayek, “The Collective Works of F.A. Hayek,””Toward a Free Market Monetary System.”

Endurance, tenacity and immutability. While these attributes may sound too passive or unsubstantial to have value in our “move fast and break things” world, they are the exact traits required to survive the fragility of a system dashing feverishly towards instability.

Antifragility, an idea popularized in the 2012 book “Antifragile” by Nassim Taleb, describes systems or phenomena that gain strength from disorder. This book, part of a larger work focused on philosophical, statistical, and economic misconceptions relating to systemic risk, uncertainty, and randomness, has become part of the larger canon of Bitcoiner manifestos. This is despite Taleb’s recent baffling divorce from the community, which while a tad perplexing, should not detract from some of his work’s takeaways.

Bitcoiners have latched onto the themes of “Antifragile” as a framework to help elucidate some of Bitcoin’s game theory. How is it that there is no silver bullet that kills Bitcoin, there is no competitor that can magically overtake it, there is no government that can shut it down, and there is no central authority that can censor or confiscate it?

But the message does not stop there. Most important to the thesis of antifragility, each attack vector and shock to the system in fact causes Bitcoin to become stronger.

As Taleb writes:

“Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty. Yet, in spite of the ubiquity of the phenomenon, there is no word for the exact opposite of fragile. Let us call it antifragile. Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better. This property is behind everything that has changed with time: evolution, culture, ideas, revolutions, political systems, technological innovation, cultural and economic success, corporate survival, good recipes (say, chicken soup or steak tartare with a drop of cognac), the rise of cities, cultures, legal systems, equatorial forests, bacterial resistance … even our own existence as a species on this planet. And antifragility determines the boundary between what is living and organic (or complex), say, the human body, and what is inert, say, a physical object like the stapler on your desk… The antifragile loves randomness and uncertainty, which also means — crucially — a love of errors, a certain class of errors.”

We have seen firsthand how the market can reward an asset that exhibits antifragility. Astute macro investor Louis Gavkal has wisely observed that this is how the U.S. treasury market has evolved.

Today, investors have institutionalized portfolio management, packaged into strategies like 60/40 asset allocations (bonds/stocks), and slightly more volatility-adjusted strategies such as risk parity. However, this love affair with the treasury market as a diversification tool has not always been the case, especially from the perspective of global investors. In fact, treasuries may be losing this status. The godfather of risk parity, Ray Dalio himself, just recently confirmed the view that he would rather own bitcoin than bonds.

What has historically given treasuries their stature of primacy for so many years was the dollar’s reserve currency role. A feat attained through war, geopolitical victories, petrodollar arrangements, and the trade-offs of increasing consumerism and domestic debt accumulation in the U.S. to supply dollars abroad. All punctuated by a parallel hyper-financialization of our economy, with regulatory incentives to own treasuries and a global system addicted to dollar-based leverage and short of adequate collateral.

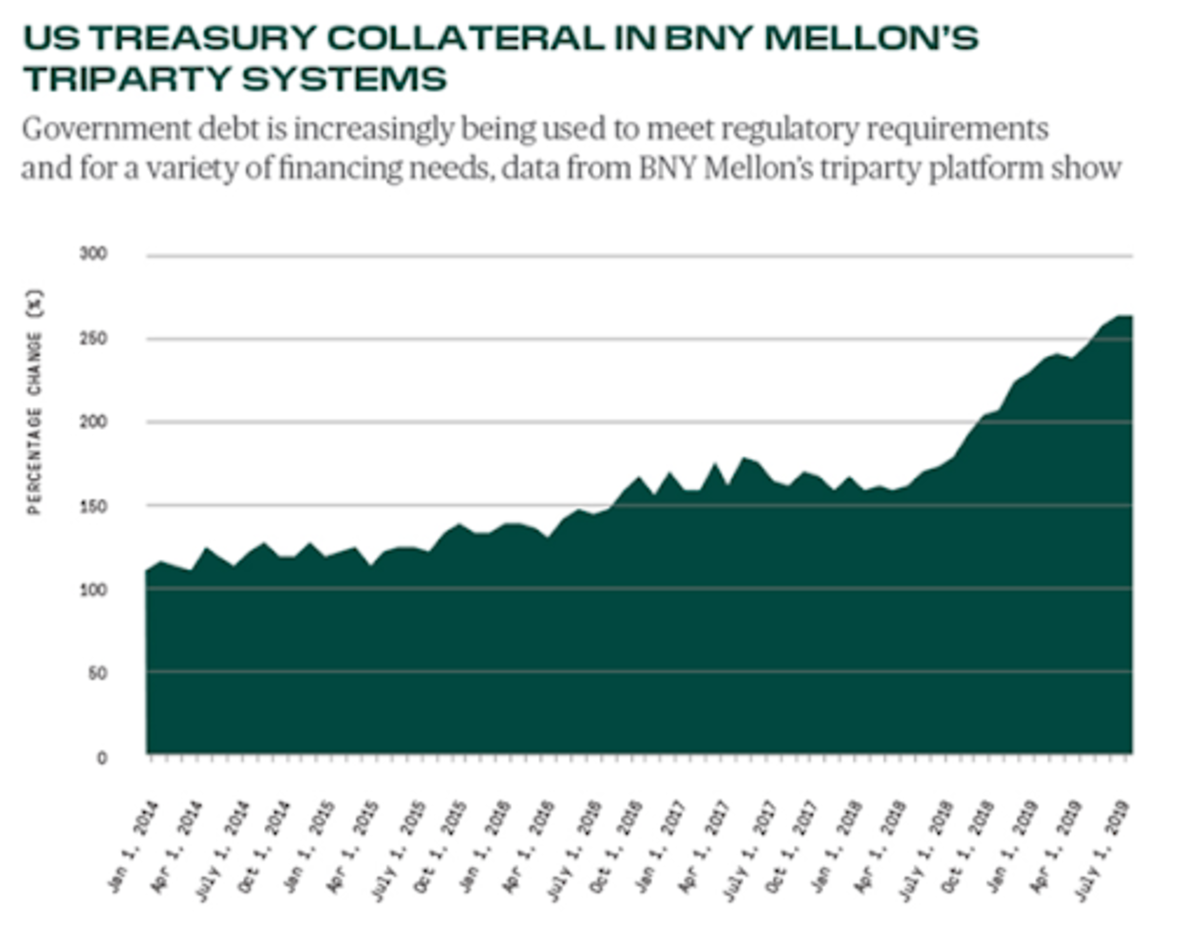

This collateral shortage has become particularly acute after quantitative easing has been significantly reducing the public supply of treasuries since 2009. All of these factors have helped create a treasury market monster with very resilient network effects for the U.S. dollar. Resilient to deleveraging elsewhere, resilient to market volatility, resilient to dollar shortages, and even resilient to cyclical inflation.

The treasury market is a massive battleship that has been chugging along full steam in one direction for many years. However, this ship is now altering its course. And this process is ever so slowly chipping away at those network effects. As the U.S. dollar necessarily loses some strength as a reserve money, the system will either need to deleverage or find a new source of collateral, a new antifragile asset.

Source: BNY Mellon

One way to think of the U.S. treasury market’s ability to maintain buyers and holders despite real interest rates, at least at negative 1% (depending on your gauge of inflation), is that this market has become a weigh station, a storage space for dollar-denominated assets, intended to balance existing portfolios of dollar-denominated equity, real estate and corporate debt holdings, as a reserve account that incentivizes participants to remain within the bounds of the existing USD ecosystem.

The Eurodollar system, U.S. dollars banked or held outside of the U.S. banking system, evolved to help accomplish this goal more efficiently at the global level.

The Eurodollar market size has exploded as the U.S. economy began to financialize in earnest: First in the early 1980s and then again in the 1990s and post-dot-com burst.

The start of this in the early 1980s coincided with the start of a 40-year bull market in U.S. treasuries:

Source: Federal Reserve Board

Such a concept of captively on-ramped capital is actually very similar to the stablecoin market in the Bitcoin and cryptocurrency ecosystems.

Source: @LudiMagistR; Glassnode

Unfortunately, for the U.S. dollar fiat ecosystem, there are signs of deterioration within its network effect. Foreign users are balking.

Source: Wolfstreet.com

A Poetic Phrase: Bitcoin Is A “Deep Structure”

“In a Paretian world, surface events can become a distraction, diverting attention from the deep structures molding these surface events. Surfaces are extraordinarily complex and rapidly evolving while the deep structures display more simplicity and stability. These deep structures are profoundly historical in nature — they evolve through positive feedback loops and path dependence. Snapshots become misleading and understanding requires a dynamic view of the landscape.” –John Hagel