Phần I: Bitcoin như một cái cây, sự bền bỉ và cấu trúc sâu

Một sự trả thù

Có lẽ nếu Tôi đã trơ trẽn hơn, tiêu đề của phần một của loạt bài này sẽ kết thúc như một thứ gì đó trêu ngươi hơn, một thứ gì đó thú vị như “Bitcoin Is A Palm Tree, And Fiat Is A Coconut.” Nhưng tốt hơn hay tệ hơn, một tiêu đề như vậy cảm thấy bão hòa với một chút quá ngắn gọn, quá nhiệt đới và tầm thường đối với một chủ đề nặng nề như vậy.

Tuy nhiên, trên thực tế, hình ảnh cây cọ thực sự rất chính xác câu chuyện ngụ ngôn về lộ trình bitcoin và fiat sẽ phát triển như thế nào khi chúng ta tiến xa hơn vào thế kỷ 21. Một cây cọ hoàng gia, roystonea oleracea, nhấp nhô một cách sốt sắng trong tiếng kêu xối xả, mặc dù không bao giờ ngừng bám chặt vào gốc rễ sâu dưới đất. Và như với bất kỳ cơn bão nào, điều cần thiết duy nhất của Darwin đối với cái cây này là một sự sống còn, để vượt qua cơn bão mà không bị tổn thương nhất có thể.

Những cây cối và công trình kiến trúc khác có thể bị gãy đổ và khuất phục trước sự khắc nghiệt của thiên nhiên, để lại nhiều ánh sáng mặt trời hơn cho cây cọ hoàng gia của chúng ta hấp thụ khi bầu trời quang đãng. Các mảnh vụn từ tất cả những thứ không đủ cứng chắc để sống sót sau cuộc tấn công, được chuyển hóa bởi các đàn mối và đám cháy, biến thành đất tươi tốt và màu mỡ. Một lớp cơ sở mới để xây dựng lại và phát triển. Một phép ẩn dụ phù hợp, trong thực tế rằng đất là phương tiện vật lý duy nhất từng được quan sát thấy trong tự nhiên có khả năng biến cái chết thành sự sống. Tương tự như vậy, một loại tiền hoàn toàn khan hiếm, không thể chê vào đâu được là phương tiện kinh tế duy nhất có khả năng đưa đời sống kinh tế vào một hệ thống tài chính đang suy tàn và suy yếu.

Cảnh báo

“Việc chuyển tiền của bạn một cách vô hại. thời gian ở đồng cỏ xa xôi

Chỉ lờ mờ nhận ra một điều gì đó khó chịu trong không khí

Tốt hơn hết, bạn nên đề phòng

Có thể có những con chó ở đó

Tôi đã nhìn qua Jordan, và tôi đã thấy

Mọi thứ không như chúng có vẻ

Bạn nhận được gì khi giả vờ nguy hiểm không có thật

Dịu dàng và ngoan ngoãn, bạn đi theo người lãnh đạo

Xuôi theo những hành lang đầy chông gai vào thung lũng thép

Thật là bất ngờ!

Một cái nhìn choáng váng trong bạn mắt

Bây giờ mọi thứ thực sự như những gì chúng có vẻ như

Không, đây không phải là một giấc mơ tồi tệ ”

-Roger Waters,“ Sheep, ”1977

Nguồn: Nareeta Martin, @LudiMagistR

Một lời tiên tri

“Bạn có nghe nói về bông hồng mọc lên từ một vết nứt trên bê tông không?

Chứng minh quy luật tự nhiên là sai, nó học cách đi mà không cần có chân.

Thật buồn cười, nó dường như bằng cách giữ ước mơ của mình, nó đã học được cách hít thở không khí trong lành.

Hoa hồng lớn lên từ bê tông còn sống lâu khi không ai khác chăm sóc. ”

–Tupac Shakur,“ Bông hồng mọc từ bê tông , ”1999

Trước khi chúng ta có thể đánh giá đầy đủ về đặc tính bền bỉ của bitcoin được đề cập ở trên, có lẽ sẽ hữu ích khi hiểu theo ngữ cảnh như thế nào và tại sao “tính chống phân mảnh” như vậy (thứ mà chúng tôi sẽ định nghĩa chi tiết hơn bên dưới) chắc chắn sẽ tự bộc lộ như một tiếng sấm, một cái tát vào khuôn mặt, cho phép tất cả chúng ta chứng kiến tiện ích bị đánh giá thấp của nó.

Để đạt được điều này, chúng ta hãy đi đường vòng một chút bằng cách sử dụng phiên bản sửa đổi của kỹ thuật đặt câu hỏi Socrate.

Lý thuyết: Dấu ấn của lớp nhà đầu tư đại chúng

Nhà đầu tư công nghệ đa năng nổi tiếng Balaji Srinivasan, trong mô hình khái niệm của mình về nền kinh tế biệt danh phi tập trung, gây tranh cãi đã tuyên bố:

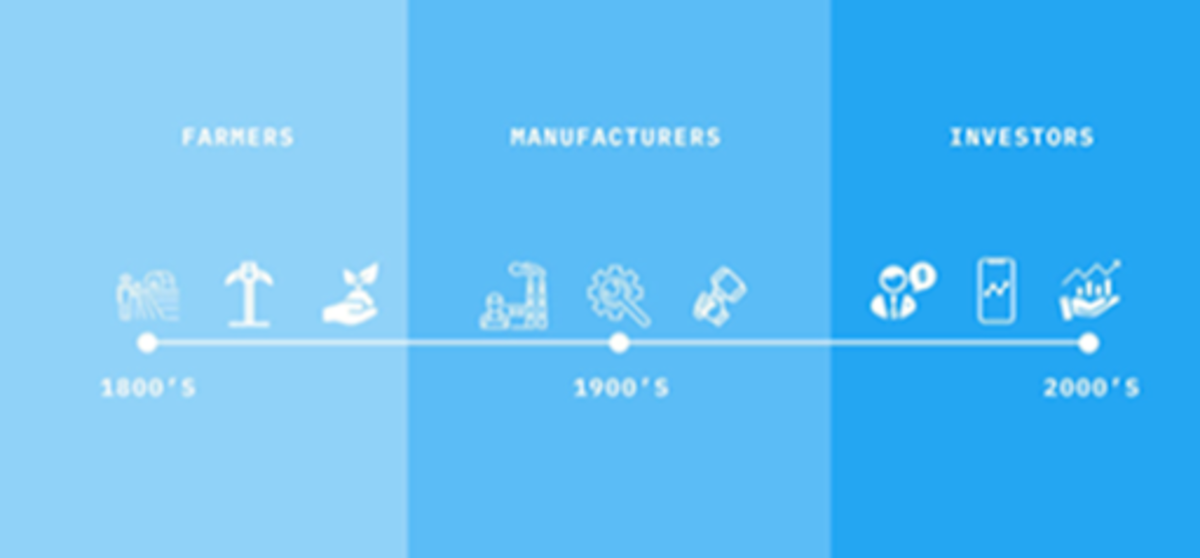

“Vào những năm 1800, mọi người đều là nông dân. Vào những năm 1900, mọi người đều tham gia sản xuất. Vào những năm 2000, mọi người đều trở thành nhà đầu tư… Và một trong những điều mà mọi người không hiểu cho đến khi họ là nhà đầu tư là ý tưởng rằng tiền rất dồi dào. ”

-Balaji Srinivasan,“ Đầu tư như Podcast hay nhất với Patrick O’Shaughnessy ”

Nguồn: Balaji Srinivasan

A Thảo luận

Chúng ta hãy xem xét tuyên bố trên theo đúng giá trị và chấp nhận nó vào lúc này như một thực tế tiên nghiệm đang phát triển. Tôi nghĩ rằng hầu hết chúng ta sẽ đồng ý rằng việc mở rộng phạm vi tiếp cận của tầng lớp nhà đầu tư như vậy thực sự đang trải qua đà leo thang nhanh chóng, đặc biệt là tăng tốc trong thế giới hậu đại dịch. Thật khó để phủ nhận những bằng chứng cứng rắn (sẽ được thảo luận bên dưới), cũng như tiêu điểm văn hóa quan sát được đã nhấn mạnh việc đầu tư vào thị trường chứng khoán tự định hướng. Bằng chứng ở khắp mọi nơi, thậm chí cuộn trên newsfeed của tôi khi tôi viết bài tiểu luận này:

“Robinhood làm việc trên tính năng để cho phép người dùng đầu tư thay đổi”

“Đầu tư dự phòng thay đổi có trở thành một chiến lược ngày càng phổ biến cho các nhà giao dịch chứng khoán mới và là một phần quan trọng của các ứng dụng cạnh tranh như Acorns, Chime và Wealthsimple. ”

Với việc IPO mang tính biểu tượng của Robinhood giờ đã khắc sâu vào ký ức gần đây của chúng ta, các tiêu đề như đã nêu ở trên là ví dụ hoàn hảo cho cuộc thảo luận của chúng ta. Đầu tư vào thị trường chứng khoán được tài trợ vi mô sẽ là hình ảnh thu nhỏ sự phát triển này hướng tới một tầng lớp nhà đầu tư đại chúng. Đầu tiên, tôi nhận thấy sự thay đổi này xung quanh tôi, trong cuộc sống chuyên nghiệp của tôi trong ngành quỹ đầu cơ, trong một nền văn hóa FOMO ngày càng tăng, lòng tham và sự lo lắng, tất cả các tương tác cá nhân của tôi với bạn bè và gia đình và trên phương tiện truyền thông xã hội. Tôi thậm chí tin rằng đây là điều mà nhiều nhà hoạch định chính sách và nhà kỹ trị đang có lương tâm mong muốn khuyến khích. Và nó làm tôi băn khoăn.

Ý nghĩa của sự chuyển đổi xã hội như vậy là gì? Và nguyên nhân gốc rễ của nó là gì?

Những câu hỏi mở như vậy nảy sinh từ quan sát này là một lý do khiến tôi bị thu hút và hấp dẫn bởi phỏng đoán của Srinivasan ngay từ đầu. Tuyên bố của ông mở đầu cho một loạt các cuộc thảo luận và liên quan đến một số chủ đề rất quan trọng.

Một số chủ đề liên quan đến tính tất yếu của nền kinh tế phi tập trung là những chủ đề sẽ được thảo luận chi tiết hơn trong phần hai của loạt bài này. Trong thời gian chờ đợi, chúng ta hãy tạo tiền đề bằng cách tìm hiểu lý do tại sao lớp nhà đầu tư đại chúng lại được khuyến khích, nó sẽ dẫn đến việc tập trung hóa nhiều hơn nữa như thế nào và tất cả những cánh cửa đã mở này đều là thang cuốn một chiều, được đảm bảo để dẫn đến những cây quyết định phụ thuộc vào con đường hơn nữa , và cuối cùng tạo ra sự mất ổn định gần như vô hạn và sự yếu ớt của hệ thống.

Và điều sẽ trở nên rõ ràng hơn rất nhiều sẽ là sự tác động qua lại tổng thể giữa tính chắc chắn và không bền vững của con đường này ở một phía của đồng tiền. Và sau đó, sự kiên trì của bitcoin ở phía bên kia, kiên nhẫn chờ đợi đến lượt nó được đưa lên không trung, quay một cách điên cuồng, mặc dù bình tĩnh và thu thập khi nó kiên nhẫn dự đoán một cuộc hạ cánh trực diện.

Một ẩn dụ về bánh sandwich

Điều mà lời tiên tri của Srinivasan vô tình phơi bày là thực tế của một giai đoạn chuyển tiếp nguy hiểm mà nền kinh tế toàn cầu hiện đang phát triển. Hiện tại, chúng ta đang ở trong một trạng thái lấp lửng lẫn lộn, bị kẹp giữa phân cấp và tập trung một cách bấp bênh.

Năng lượng văn hóa của trạng thái thời gian linh hoạt này chắc chắn gây ra “cảm giác khó chịu trong không khí” nhất định, mặc dù có thể thấy rõ sự bất mãn ngày càng tăng. Và cũng giống như các sự kiện của đại dịch COVID-19 đã thúc đẩy sự gia tăng của nhiều xu hướng, một trong những xu hướng này thực sự là biểu hiện của một tầng lớp nhà đầu tư “vô sản” và đang mở rộng mạnh mẽ. Và mặc dù sự tiến bộ như vậy có nhiều thuộc tính tích cực-từ việc tự trao quyền cho bản thân, cơ hội tạo ra của cải mới trong ngắn hạn, và giáo dục tài chính về thị trường, quản lý rủi ro, tiền tệ và lý thuyết kinh tế-tất cả những lợi ích như vậy thật đáng buồn là sai lầm và ngắn hạn-nhìn thấy rõ. Cuối cùng, những lợi ích rất hữu hình này sẽ bị pha loãng và tiêu diệt bởi những thế lực đáng ngại.

Những lý do chính giải thích tại sao việc hàng hóa của tầng lớp nhà đầu tư là một diễn biến nguy hiểm chủ yếu có thể là do thời điểm, bối cảnh lịch sử và tác động của những gì xã hội nhà đầu tư đại chúng này sẽ yêu cầu dưới dạng các hiệu ứng phái sinh thứ hai và thứ ba.

Hãy kiên nhẫn bên dưới, vì phần đầu tiên này không tránh khỏi nặng nề với một số dữ liệu tài chính và thuật ngữ. Tuy nhiên, những dữ liệu đó là cấp thiết để giúp chúng tôi hiểu được bức tranh toàn cảnh hơn về những gì đang diễn ra và sẽ chi trả cổ tức sâu hơn cho bài báo và loạt bài khi chúng tôi mở rộng những ý tưởng lớn hơn trong luận án của mình.

Tôi không phải là người tận thế. Tôi không sống trong boongke. Tôi đã chứng kiến quá nhiều nhà đầu tư trở thành nạn nhân của những câu chuyện quá lạc quan, bỏ lỡ những đợt lạm phát tài sản lớn khiến những tiêu cực đó làm xáo trộn. Tuy nhiên, mục đích của bài tiểu luận này không phải là đưa ra một số luận điểm đầu tư ngắn hạn. Điều đó nói lên rằng, những gì tôi đã bắt đầu chứng kiến ngày càng rõ ràng với tư cách là một nhà đầu tư, với tư cách là một thành viên của xã hội quan tâm đến thế giới mà con tôi thừa hưởng, đang ngày càng tăng bằng chứng về một cái bẫy không thể tránh khỏi. Một cái bẫy chỉ có một giải pháp thực tế. Vì vậy, dữ liệu tài chính ở đây chỉ đơn thuần là một công cụ, một ngôn ngữ để giúp chúng ta thấy được cái nhìn sâu sắc này. Trên thực tế, thông điệp chính của loạt phim này không phải là về tài chính và thị trường, mà nhiều hơn về bản chất con người, lịch sử và những động lực tác động cũng như xung đột ý thức hệ sẽ ảnh hưởng đến kết quả của phần lớn thế kỷ này.

Vì vậy, hãy chịu đựng tôi khi tôi đưa chúng ta đi sâu hơn nữa xuống cái hố thỏ gồm những khối định mệnh trong chuỗi phản ứng của chúng ta.

Khối Một: Các Vấn đề Bối cảnh Lịch sử. Hóa ra Thời điểm là Tất cả

Một tầng lớp nhà đầu tư đại chúng, được thúc đẩy bởi những tiền đề sai lầm và những khuyến khích sai lầm, trớ trêu thay lại hình thành sau một thời kỳ lạm phát tài sản lịch sử chưa từng có.

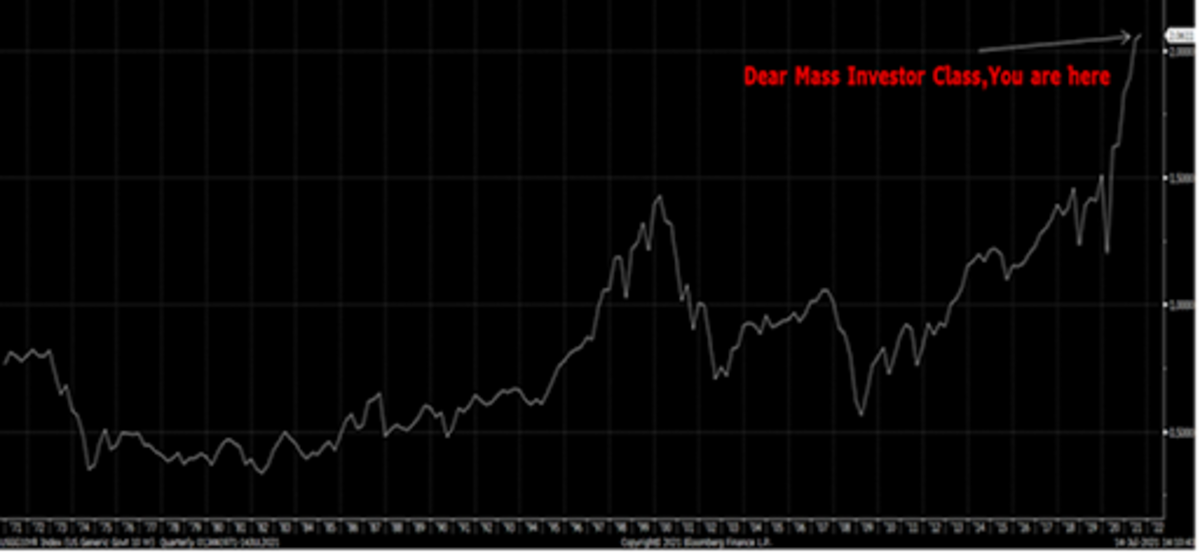

Chúng ta vừa chứng kiến hơn 40 năm lạm phát tài sản tài chính, nợ nần chồng chất, phá vỡ quy định và không rõ ràng tiền tệ. Một thị trường tăng giá trái phiếu hoành tráng trong đó lãi suất phi rủi ro đã tăng từ 16% xuống gần bằng 0, thị trường chứng khoán so với năng lực sản xuất của chúng ta đang ở mức kỷ lục (xem biểu đồ bên dưới), hầu hết các chỉ số định giá đều ở mức cao trong lịch sử và hành vi phi lý đã mở rộng đáng kể (ví dụ như SPAC, r/WallStreetBets, cổ phiếu meme, nợ ký quỹ bán lẻ và tất nhiên là nhiều túi của vũ trụ”tiền điện tử”).

Đồng thời, đòn bẩy của chính phủ và doanh nghiệp cũng ở mức cực đoan. Các số liệu thống kê này thậm chí còn trở nên thừa thãi hơn khi tính đến các khoản nợ ngoại bảng của chính phủ như an sinh xã hội, y tế, nghĩa vụ lương hưu và ngân sách quốc phòng ngoại bảng. Điều này ngoài việc bao gồm các giả định về hướng dẫn của công ty và rất nhiều nhóm quản lý công ty đang hết sức sáng tạo với các thủ thuật bổ trợ thu nhập và các chiến lược kỹ thuật kế toán tích cực. Nói cách khác, nhà đầu tư cá nhân đang chuyên nghiệp hóa khi kết thúc một trong những bữa tiệc thất bại Homeric lớn nhất, nhiều nhất mọi thời đại. Hãy tha thứ cho phép ẩn dụ bóng chày sáo rỗng, nhưng điều này giống như một cầu thủ được gọi lên từ các giải đấu nhỏ ngay trước khi mùa giải diễn ra, sau trận chung kết World Series đầy kịch tính kéo dài bảy trận.

Đây có thực sự là một sự phát triển tốt cho xã hội? Điều này thực sự khá điển hình về hành vi được quan sát và tham gia xảy ra trong thời kỳ cao điểm của thị trường tăng giá. Tuy nhiên, có một vài điểm khác biệt chính ở đây so với sự cố vỡ bong bóng điển hình.

Đầu tiên, chúng tôi đề cập đến hành vi như vậy trong bối cảnh các khoản đầu tư này được thực hiện dưới vỏ bọc của sự chuyên nghiệp mới hình thành và sự thay đổi nghề nghiệp được trao quyền. Có cảm giác được hưởng sự giàu có và kỳ vọng từ cả các nhà hoạch định chính sách cũng như các nhà đầu tư mới rằng họ có quyền đạt được sự giàu có từ thị trường vốn và làm như vậy với rất ít rủi ro đi kèm. Hơn nữa, bằng chứng là tỷ lệ tham gia lao động giảm, một xã hội các nhà đầu tư tạo ra rủi ro kép. Khi có nhiều người từ bỏ các phương thức lao động khác, chúng ta trở thành một xã hội của “những người cho thuê” chứ không phải là “những người làm”. Chúng ta đảo ngược mũi tên của lịch sử vốn luôn dẫn đến việc tăng cường chuyên môn hóa và phân công lao động. Vì vậy, không chỉ ngày càng có nhiều cá nhân tiếp xúc với các tài sản tài chính hơn bao giờ hết, mà nhóm thuần tập đang mở rộng này đã làm như vậy với chi phí cơ hội của việc làm bị bỏ qua và tiền lương kiếm được ở nơi khác.

Tiền đặt cược cao hơn và tỷ lệ sai sót thấp hơn. Và hành vi như vậy thực sự đang được chứng thực cả về mặt văn hóa, như một phương tiện nổi dậy chống lại tầng lớp giàu có và về mặt chính trị, như một quyền tự do đối với quyền sở hữu tài sản để được phân phối nhiều hơn, mà không liên quan đến giá trị cơ bản và rủi ro của những tài sản đó. Điều này khác với bong bóng tài chính nhất thời đơn giản. Đây là một khinh khí cầu bay lên qua tầng bình lưu, không bao giờ cảm nhận được sự ôm chặt của trái đất nữa.

Hoa Kỳ vốn hóa thị trường chứng khoán so với GDP tính bằng đô la danh nghĩa, từ năm 1971 đến nay. Nguồn: @LudiMagistR, Bloomberg

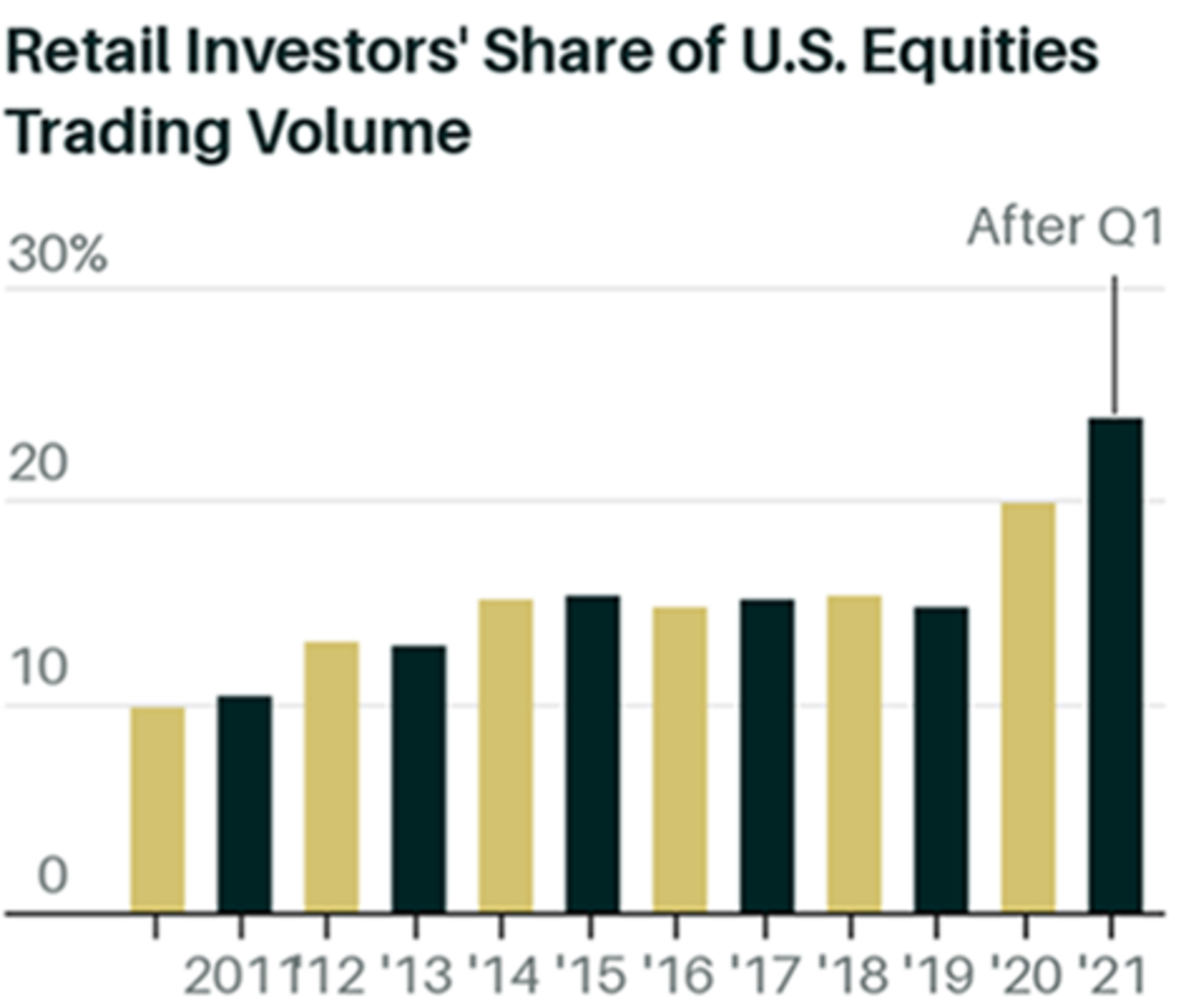

Việc áp dụng tầng lớp nhà đầu tư đại chúng đang tăng tốc.

Tỷ lệ vốn hóa hàng năm của dòng vốn đầu tư vào năm 2021 là khoảng 1 nghìn tỷ đô la. Đối với một số góc nhìn, con số này lớn hơn tổng dòng vốn tích lũy vào cổ phiếu trong toàn bộ 20 năm qua!

Nguồn: Bank of America; Michael Hartnett

Biểu đồ trên minh họa dòng vốn đầu tư hàng năm trị giá 1 nghìn tỷ đô la vào cổ phiếu vào năm 2021, so với dòng vốn chủ sở hữu tích lũy 800 tỷ đô la từ năm 2001 đến năm 2020. Hãy để điều đó chìm trong một phút trước khi tiếp tục bài luận này. Ngày nay, chúng ta thấy rất nhiều biểu đồ, meme và số liệu thống kê điên rồ và chưa từng có, đến nỗi có thể dễ dàng phủ nhận biểu đồ này. Nhưng điều này thực sự nói lên một điều gì đó sâu sắc gây rắc rối về nơi mà mọi thứ đang hướng tới.

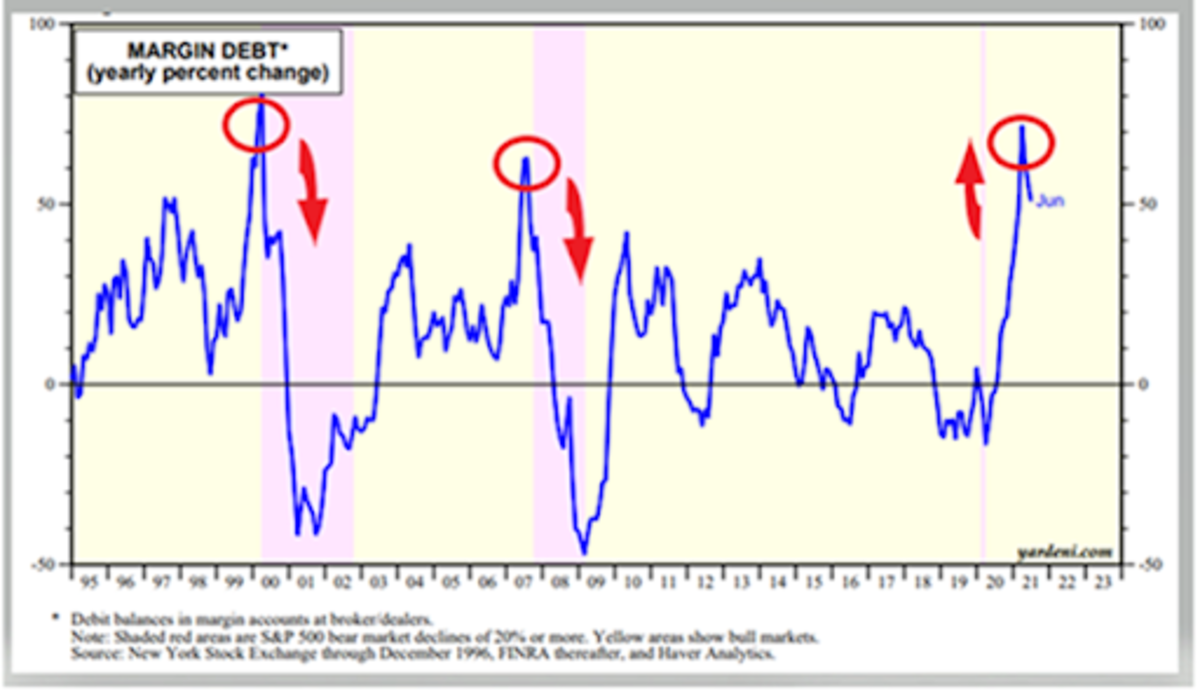

Nợ ký quỹ cho giao dịch cổ phiếu có đòn bẩy, được Cơ quan quản lý ngành tài chính (FINRA) theo dõi, trước đây là dấu hiệu cho thấy sự hào hứng và tham lam của nhà đầu tư cá nhân (hoặc “bán lẻ”) trong thị trường chứng khoán.

Biểu đồ dưới đây thể hiện tỷ lệ phần trăm gia tăng hàng năm của nợ ký quỹ, vốn trước đây đã dự đoán trước các cuộc suy thoái, được đánh dấu bằng các vùng tô màu tím. Tuy nhiên, chúng ta có thể thấy trong giai đoạn gần đây, tỷ suất lợi nhuận đã tăng với tốc độ chưa từng có trong lịch sử, có thể đạt đỉnh trong ngắn hạn.

Nhưng quan sát chính ở đây là sự gia tăng nhanh chóng này đã xảy ra sau thanh màu tím đó, chứ không phải trước nó. Nợ ký quỹ không xảy ra trước một cuộc khủng hoảng mà là phản ứng của nó. Chúng tôi đã thấy những gợi ý về điều này vào năm 2009, nhưng đó là sau một đợt thanh trừng lớn các đòn bẩy ngân hàng và nhà ở, đồng thời ghi nhận giá trị tài sản lớn. Cuộc khủng hoảng COVID-19 đã không cho phép một cuộc thanh trừng như vậy và đã thiết lập các chính sách để phục hồi đáng kể đầu tư cổ phần bán lẻ. Đây là hành vi mới.

Nguồn: Ed Yardeni (yardeni.com); NYSE; FINRA; @LudiMagistR

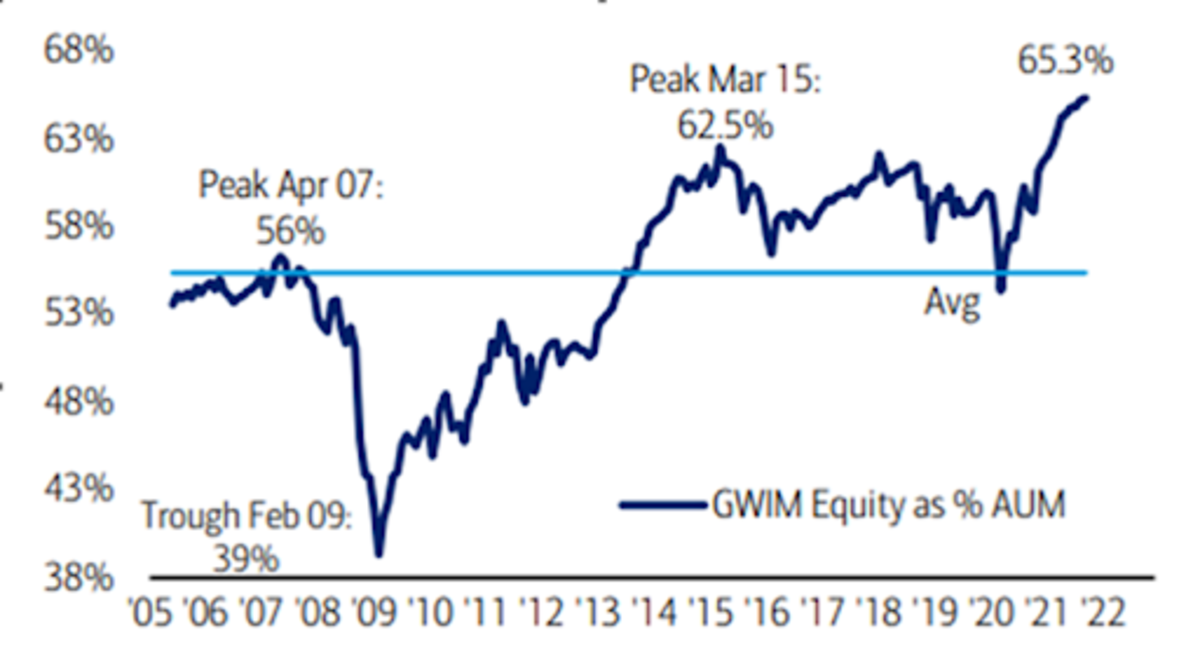

Phân bổ vốn chủ sở hữu của khách hàng Wealth Management của Bank of America (BofA) đang ở mức cao nhất mọi thời đại.

BofA sở hữu vốn chủ sở hữu khách hàng tư nhân theo tỷ lệ phần trăm tài sản được quản lý. Nguồn: Bank of America; Michael Hartnett

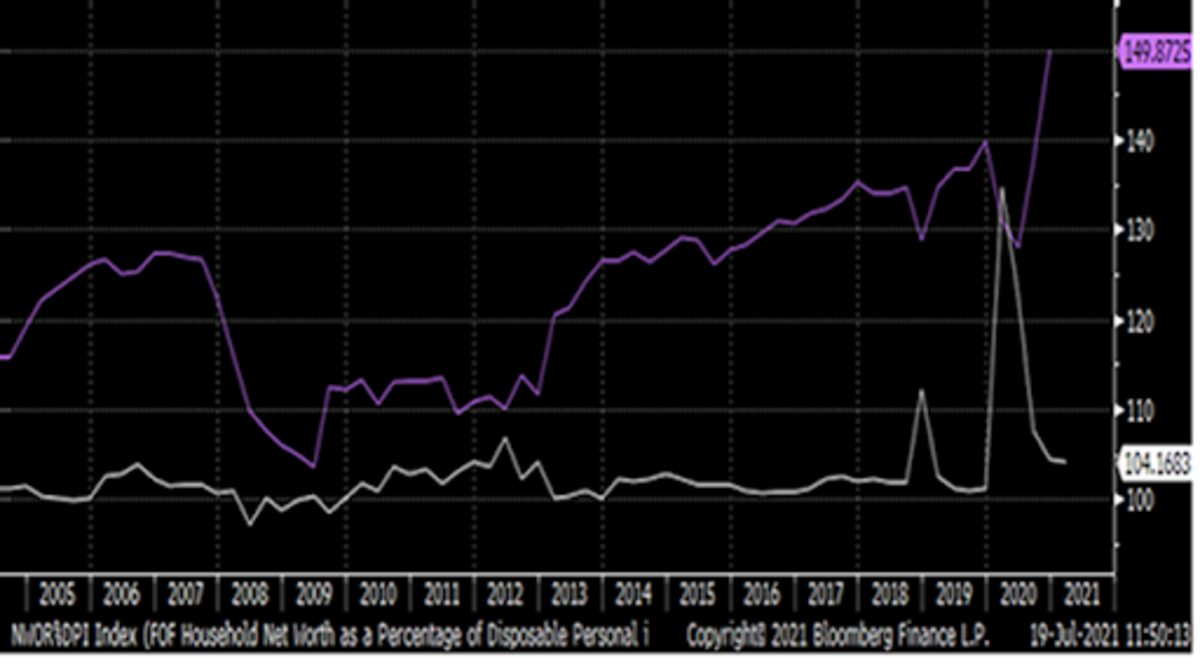

Giá trị ròng của hộ gia đình tính theo phần trăm thu nhập cá nhân khả dụng (màu tím), so với tỷ lệ tiết kiệm cá nhân Tỷ lệ tăng trưởng hàng năm/tỷ lệ tăng trưởng giá trị ròng hàng năm (đường trắng. Nguồn: @LudiMagistR, Bloomberg, Cục Dự trữ Liên bang St. Louis

Điều mà biểu đồ cuối cùng này trực tiếp ở trên chứng tỏ rằng các cá nhân ở Hoa Kỳ không còn tiết kiệm từ thu nhập vượt mức mà từ lạm phát tài sản. Rủi ro nhất định và các tài sản tài chính nhạy cảm với lạm phát hiện là kho lưu trữ giá trị chính đối với hầu hết các hộ gia đình có khả năng sở hữu chúng.

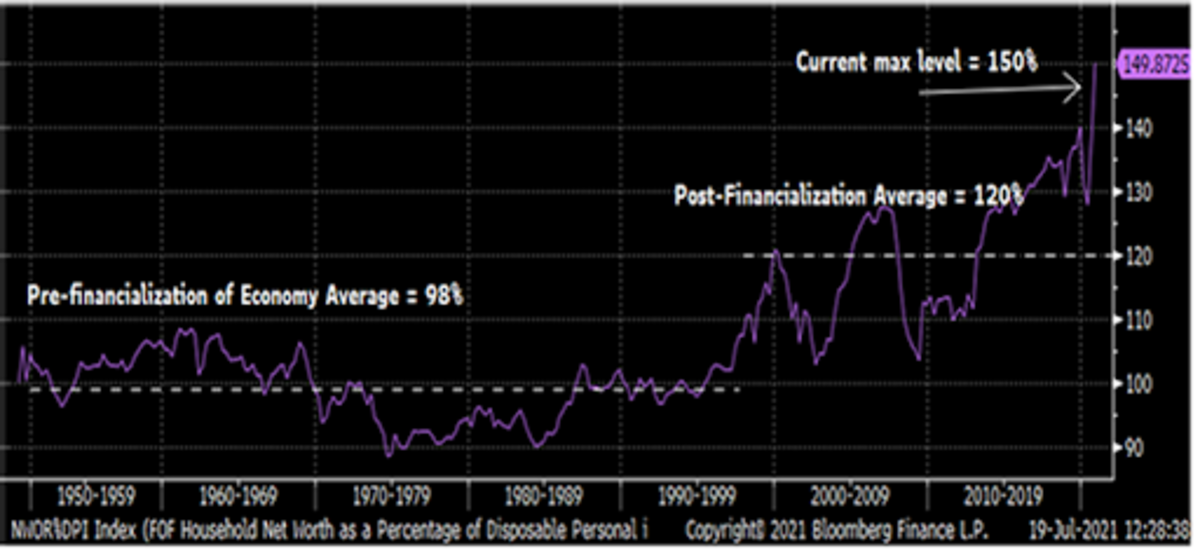

Đối với bối cảnh lịch sử lớn hơn, dưới đây là giá trị ròng của cùng một hộ gia đình tính theo tỷ lệ phần trăm thu nhập cá nhân khả dụng, quay trở lại năm 1945.

Nguồn: @LudiMagistR, Bloomberg, Cục Dự trữ Liên bang St. Louis

Cái chết nếu sự phá hủy sáng tạo

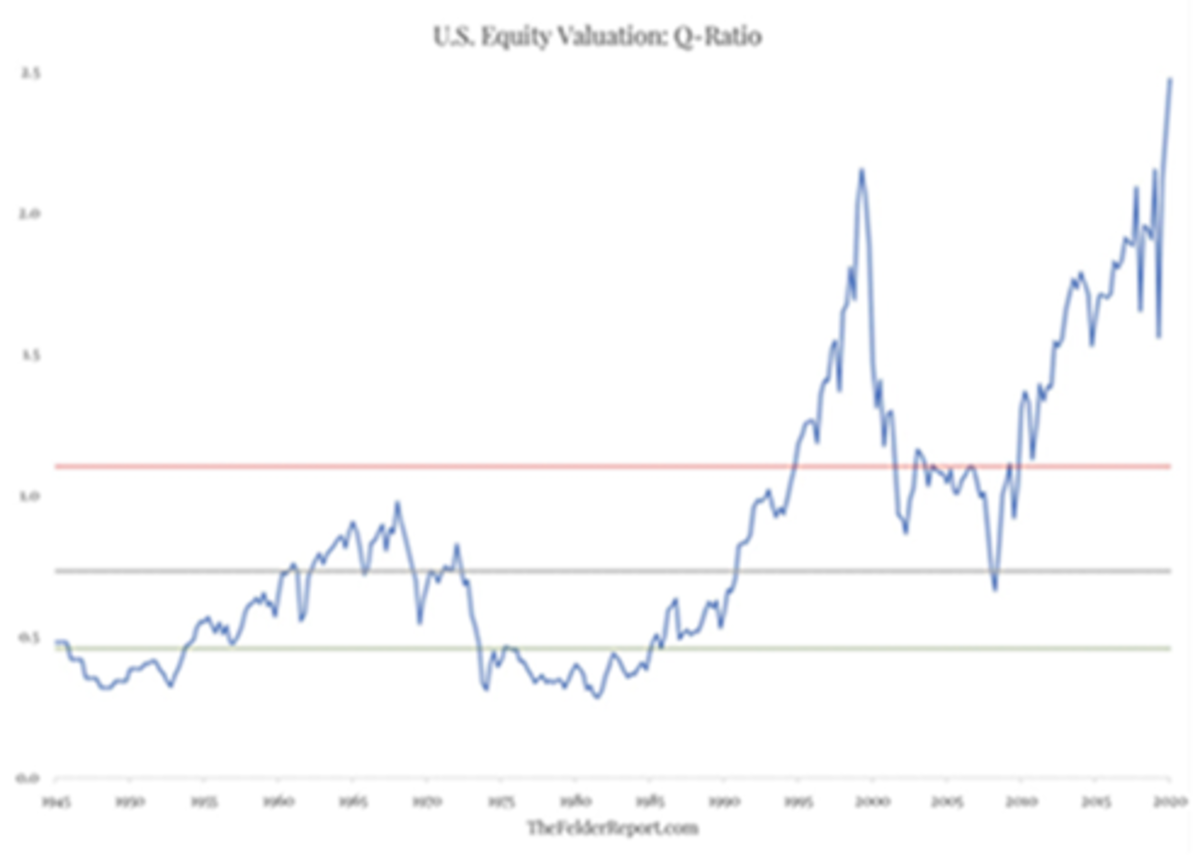

Dưới đây là biểu đồ của một chỉ số được gọi là Thương số Tobin, còn được gọi là “Tỷ lệ Q”. Về bản chất, nó là tỷ lệ vốn hóa hiện tại của thị trường chứng khoán, chia cho chi phí thay thế trong thế giới thực của tài sản liên quan đến vốn chủ sở hữu đó.

Như được hình dung trong biểu đồ bên dưới, tỷ lệ này ở mức chưa từng có trong lịch sử. Biểu đồ dao động từ sau Thế chiến II đến nay và thể hiện rằng định giá vốn chủ sở hữu hiện gần gấp rưỡi giá trị thay thế của chúng. Tỷ lệ này so với tỷ lệ trung bình 75 năm gần hơn với giá trị thay thế.

Phải thừa nhận rằng phân tích này không mang nhiều sắc thái, vì nền kinh tế của chúng ta đã chuyển sang thời đại thông tin được đặc trưng bởi nền kinh tế kỹ thuật số hơn, theo đó tài sản trở nên vô hình hơn và do đó khó định giá các chi phí thay thế như tài sản trí tuệ hơn và thiện chí của các hiệu ứng mạng. Nhưng ngay cả khi chúng ta tính đến sự thay đổi này, tỷ lệ Q hiện tại vẫn ở mức hơn ba lần giá trị thay thế, so với kỷ nguyên phá sản trước dot-com những năm 1990 với giá trị thay thế trung bình 1,4 lần và post-dot.com trung bình thời kỳ phá sản gần gấp 2,3 lần giá trị thay thế.

Bất kể bạn phân tích dữ liệu như thế nào, điều này chứng tỏ mức độ tuyệt đối của các công ty được định giá tài chính theo cách hoàn toàn khác biệt với thực tế kinh tế của họ. Những công ty được gọi là “thây ma” không nên tồn tại trong một thị trường tự do thực sự, thường mang một số lượng lớn nợ không sinh lời để duy trì bản thân, phát triển mạnh mẽ trong một thế giới mới dũng cảm như vậy. Những thực thể này bẫy tiền tốt và giữ nó hóa đá bên trong các cấu trúc đang phân hủy. Là một nhà đầu tư chuyên nghiệp dành nhiều thời gian đầu tư vào tín dụng doanh nghiệp có lợi suất cao, tôi thấy điều này hàng ngày rất điên rồ.

Tại một số thời điểm, cách duy nhất để điều hòa sự mất cân đối đó là bằng cách tái cơ cấu hàng loạt, phá sản và vỡ nợ hoặc thông qua lạm phát. Lạm phát hành động để nâng cao mẫu số của giá trị thay thế, trong một liều thuốc giả kim thuật về thái độ bề ngoài. Lạm phát, như đã chứng kiến trong suốt lịch sử nhân loại, cho đến nay là giải pháp hợp lý hơn cho các nhà kinh tế, các nhà đầu tư Phố Wall và tất nhiên là các chính trị gia có tầm nhìn từ hai đến bốn năm về thế giới.

Nhưng thực tế trớ trêu là việc nhận ra như vậy cũng là để giải thích cách chúng tôi đến đây ngay từ đầu.

Tobin’s Quotient, 1945 đến nay: Định giá thị trường chứng khoán so với giá trị thay thế của nền kinh tế. Nguồn: Báo cáo của Felder

Sự từ chối chất lượng

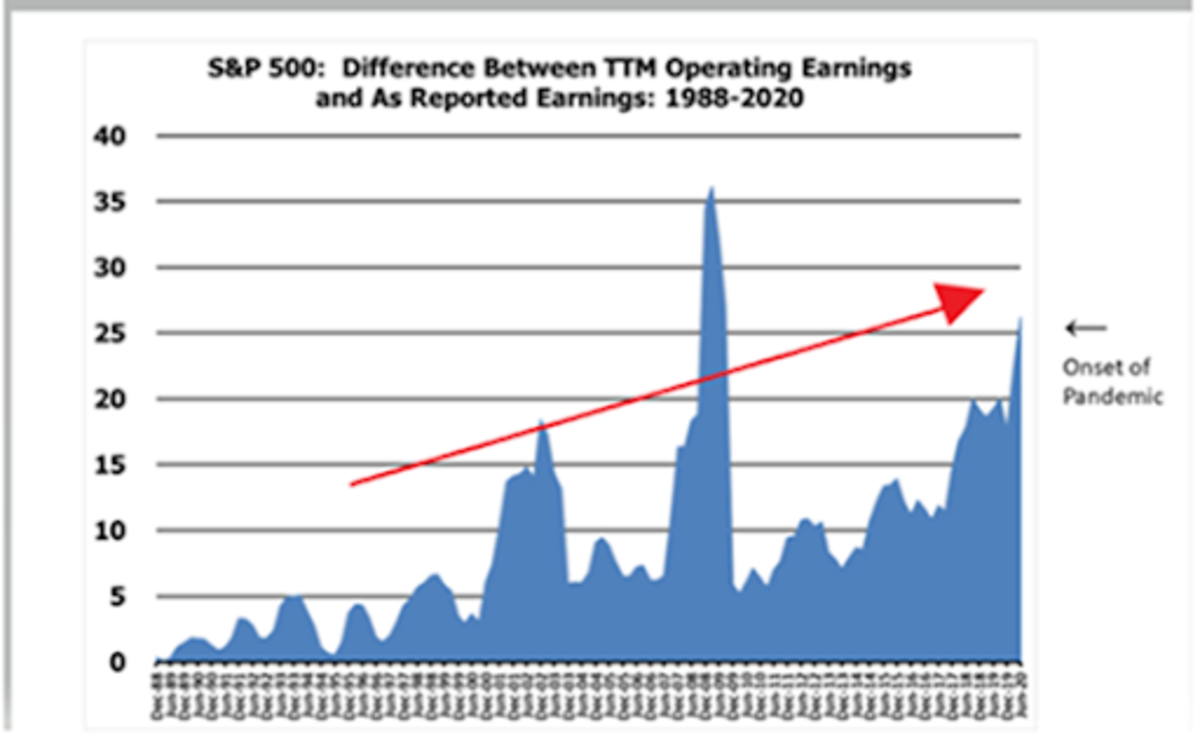

Dưới đây, chúng ta có thể quan sát thêm bằng chứng về sự suy giảm chất lượng. Trong trường hợp này, chúng tôi không chỉ đề cập đến sự sụp đổ của sự phá hủy sáng tạo và chất lượng bảng cân đối kế toán, mà là chất lượng của chính thu nhập tổng thể của công ty.

Chính những chỉ số mà chúng tôi tin tưởng để giúp chúng tôi xác định chắc chắn thế giới dữ liệu phức tạp xung quanh chúng tôi đã bị đánh bạc và thao túng đến mức mà thước đo đã trở thành mục tiêu. GAAP, hay”các nguyên tắc kế toán được chấp nhận chung”, là một giao thức kế toán được thiết kế để hạn chế việc giảm thu nhập thông qua các phần bổ trợ không rõ ràng, tùy ý và gây hiểu lầm. Đôi khi, có những điều chỉnh không phải GAAP thực sự hợp lệ cần được thực hiện để có được bức tranh chính xác về tiềm năng thu nhập tỷ lệ chạy thực sự của công ty. Tuy nhiên, về tổng thể, những điều chỉnh “không phải GAAP” như vậy đối với báo cáo GAAP có xu hướng tạo ra bức tranh về tính toàn vẹn và độ tin cậy thấp hơn.

Mặc dù vậy, chúng tôi đã quá quen với những điều chỉnh đến mức những người tham gia thị trường và cơ quan quản lý đã chấp nhận sự sai lệch dần dần một cách không liên kết. Có lẽ không có gì ngạc nhiên khi các điều chỉnh không phải GAAP lần đầu tiên “ bắt nguồn từ cấu trúc của báo cáo tài chính ”vào năm 1988, khi nhiều chính sách tài chính hóa nền kinh tế được đẩy mạnh. Cũng cần nhắc lại rằng hầu hết chi phí bồi thường dựa trên cổ phiếu được cộng lại vào thu nhập không phải GAAP. Vì vậy, có một động lực tự tham chiếu ở đây, khi thu nhập không phải GAAP thúc đẩy sự xuất hiện của lợi nhuận, giúp tăng định giá cổ phiếu, do đó làm tăng mức bồi thường dựa trên cổ phiếu đang giúp tăng thu nhập ngay từ đầu !

Biểu đồ dưới đây vẽ biểu đồ chênh lệch của thu nhập không phải GAAP trừ đi thu nhập GAAP:

Mức chênh lệch này có xu hướng tăng đột biến trong các cuộc suy thoái do các khoản lỗ không hoạt động tích lũy. Nhưng thú vị là trong những năm sau suy thoái, xu hướng này tiếp tục đi theo hướng chất lượng yếu hơn.

Nguồn: Nghiên cứu về Lark

Khối thứ hai: Khinh khí cầu

Kết quả của tình huống này là khí cầu dễ vỡ của hệ thống nhanh chóng, đòi hỏi sự phụ thuộc vào đường đi xác định của dữ liệu gia tăng thao túng, hỗ trợ của chính phủ, quy định và sự can thiệp của thị trường tự do.

Bối cảnh định giá lịch sử và hiệu suất tài sản như đã trình bày ở trên có nghĩa là việc mở rộng khả năng tiếp xúc tài sản tài chính với một nhóm dân số lớn hơn và đa dạng hơn sẽ tạo ra rủi ro hệ thống không thể chấp nhận được cho nền kinh tế về lâu dài. Để mượn một cụm từ lý thuyết trò chơi, thị trường chứng khoán trở thành một điểm thất bại duy nhất.

Như tôi đã trình bày trong một bài viết trước, “Suy nghĩ quá nhỏ và cạm bẫy của tường thuật lạm phát”, nó cũng trở thành một phương tiện in tiền ngấm ngầm thông qua việc tạo ra tài sản tài chính, thay vì hơn thế nữa sự mở rộng cung tiền rõ ràng của thế hệ cha mẹ và ông bà của chúng ta. Động cơ thổi phồng lên theo nghị định về rủi ro đạo đức-hoặc lạm phát tài sản tài chính được bảo đảm ngầm-thậm chí còn dễ thực hiện hơn khi công nghệ ngày càng tạo ra nhiều sản phẩm và dịch vụ rẻ hơn hoặc hoàn toàn không tốn phí, và khi những hạn chế về nguồn cung như chúng ta đang gặp phải hiện nay khiến tiêu dùng về”thứ”vật lý ít mong muốn hơn hoặc thậm chí là không thể trong một số trường hợp.

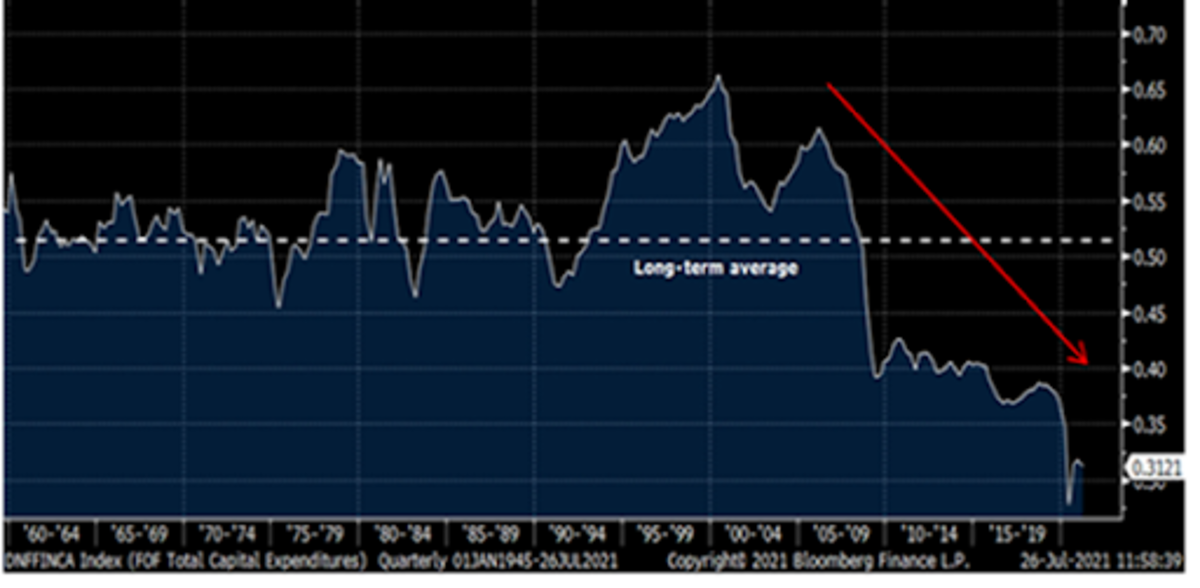

Các thị trường nợ được định giá thích hợp tạo ra rào cản trở lại đối với đầu tư chỉ khuyến khích những nỗ lực có thể tạo ra vốn sản xuất mới. Nợ quá rẻ khuyến khích việc tận dụng nguồn vốn hiện có, mà không cần hoặc mong muốn có được bất kỳ lợi nhuận sản xuất nào. Và ngay cả khi các khoản đầu tư vốn mới cuối cùng được thực hiện, động cơ rõ ràng là làm như vậy với nguồn tài chính rẻ đó, chứ không phải từ tiết kiệm và dòng tiền. Điều này cuối cùng khiến các nhà phân bổ vốn sản xuất thậm chí rơi vào con đường sử dụng đòn bẩy quá mức.

Trong khi đó, khi tài sản tăng giá, cách duy nhất để duy trì mức sống mong muốn là chuyển bất kỳ khoản tiết kiệm nào thay vào đó vào các tài sản tài chính rủi ro hơn như cổ phiếu, trái phiếu và địa ốc. Điều này là do lợi tức đầu tư để hình thành vốn mới luôn mất nhiều thời gian hơn so với việc thu hồi vốn tồn kho hiện có khi lạm phát đã giảm nhưng được đảm bảo bởi rủi ro đạo đức hệ thống. Thêm vào đó là thực tế là lãi suất bị áp chế và thao túng đang ăn cắp ngay từ chính tương lai mà vốn mới sẽ được đầu tư (thảo luận thêm bên dưới). Điều này càng làm mất tác dụng của bất kỳ khoản đầu tư vật chất nào vào nguồn vốn mới.

Biểu đồ dưới đây vẽ tỷ lệ tổng chi tiêu vốn của Hoa Kỳ tính bằng đô la danh nghĩa, chia cho mẫu số của tiền cơ sở được đưa vào hệ thống, được đo bằng cung tiền M2. Kể từ khi đạt đến đỉnh điểm cuộc khủng hoảng dot-com, đầu tư vào việc hình thành vốn mới đã giảm mạnh so với việc tạo ra tiền mới. Điều này đặt ra một câu hỏi tu từ là tất cả lượng tiền thừa mới đang chảy đi đâu, nếu không muốn nói là hình thành vốn mới. Tất nhiên, câu trả lời là tài sản tài chính.

Nguồn: Bloomberg; @LudiMagistR

Vì vậy, các ưu đãi rõ ràng như một con sên cứng cỏi của Stoli. Và, trong hầu hết 30 năm qua, chỉ những người giàu có mới tham gia vào thiết kế trò chơi này, giành được một chỗ ngồi trên bàn với tài sản hiện có của họ, “ bằng chứng về cổ phần .”

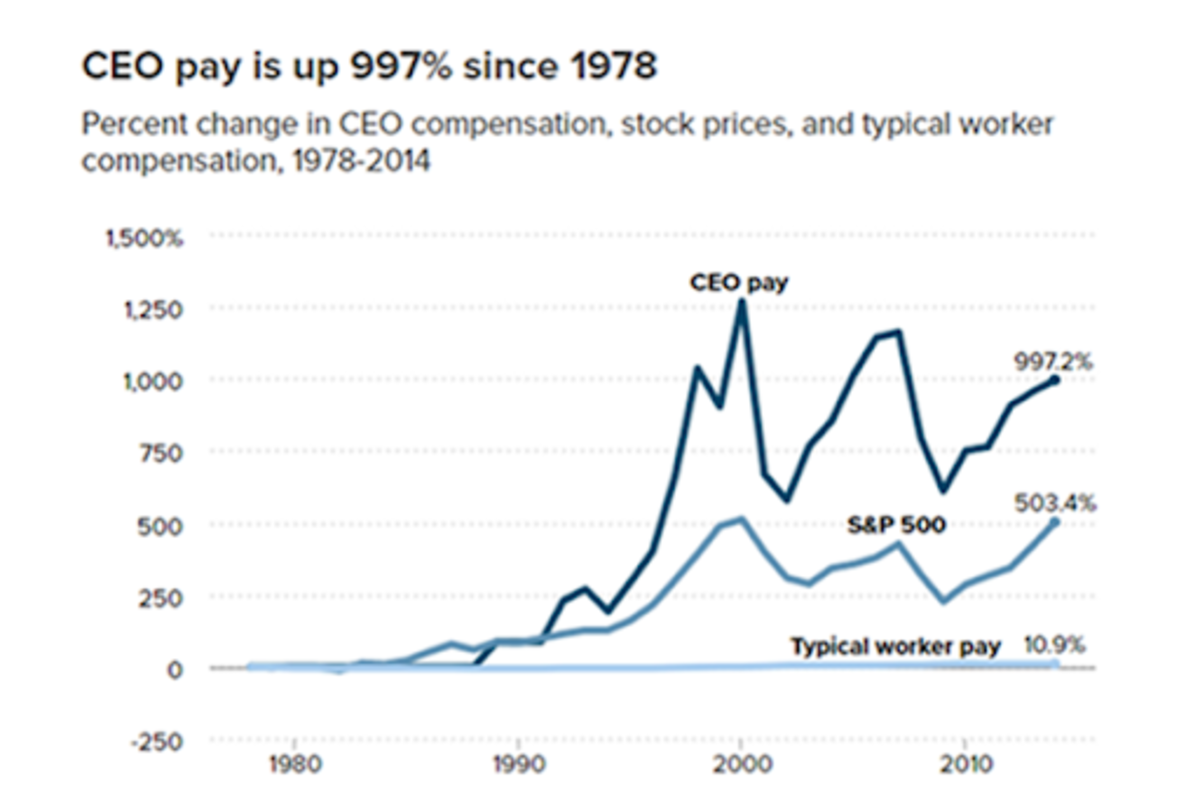

Tuy nhiên, ngày càng rõ ràng rằng rủi ro đạo đức phổ biến ở khắp mọi nơi, sự thu hẹp tùy chọn thời gian hơn nữa và tiết kiệm mới đúc là nhiều nhất giai đoạn tiếp theo hiệu quả trong cây quyết định về ý chí tự do sai lầm này. Các nhà hoạch định chính sách ở cả hai phía của lối đi có động lực để nắm bắt một câu chuyện như vậy. Họ sẽ hướng tới mục tiêu thúc đẩy giá trị ròng của tầng lớp trung lưu thay vì sách vở cũ liên quan đến việc cải thiện thu nhập của tầng lớp trung lưu, giáo dục, mạng lưới an toàn xã hội và phân bổ lại thuế. Trong khi đó, phe hữu sẽ sẵn sàng vượt qua đòn roi của họ từ kinh tế học tiền tệ trọng cung giảm nhỏ giọt, với “hy vọng” tự huyễn hoặc rằng chế độ quân sự Mỹ sẽ chia sẻ của cải, và tương tự như vậy sẽ nắm lấy lạm phát tài chính và chủ nghĩa tư bản xã hội hóa. Cánh hữu sẽ coi việc tập trung hóa thị trường vốn như vậy là khó chịu, nhưng tốt hơn là một sự thay thế của chủ nghĩa xã hội Keynes và phân phối lại. Cả hai bên sẽ đánh đổi các nguyên tắc cốt lõi của mình để có được một giải pháp thực sự mang lại kết quả, mặc dù với chi phí rất lớn.

Nếu bạn là một nhà hoạch định chính sách khi nhìn vào biểu đồ dưới đây, đâu sẽ là cơ chế ít rủi ro nhất và rõ ràng nhất để điều chỉnh sự khác biệt lớn như vậy? Dễ dàng: Chỉ cần gắn “lương công nhân thông thường” với S&P 500 và bùng nổ! Nhiệm vụ đã hoàn thành!

Nguồn: Viện Chính sách Kinh tế; Dữ liệu kinh tế của Cục Dự trữ Liên bang (FRED)

Được. Vì vậy, chúng ta hãy giả sử rằng chúng ta hiện đã có quả bóng lăn và thực sự đang bắt đầu ràng buộc việc trả lương cho người lao động với thị trường chứng khoán thông qua nhiều phương tiện khác nhau. Nhưng làm thế nào một kỳ tích như vậy được hoàn thành? Không phải chính phủ có thể buộc người sử dụng lao động trả lương theo hình thức chỉ số thị trường chứng khoán.

Không, không trực tiếp. Câu trả lời nằm trong một công thức pha trộn của các biện pháp khuyến khích đã thay đổi. Rủi ro đạo đức và hậu quả tiềm ẩn của giá cổ phiếu như đã mô tả ở trên chắc chắn là tâm điểm của một chiến lược như vậy.

Nhưng còn vô số những yếu tố khác: Tiết kiệm cá nhân cao hơn về mặt tài chính với động cơ đầu tư bất kỳ khoản tiết kiệm vượt mức nào; những nỗ lực phi toàn cầu hóa khuyến khích công dân Hoa Kỳ đầu tư và tiết kiệm trong nước hơn là nhập khẩu tiêu dùng từ Trung Quốc; và sự tiến bộ tự nhiên của đổi mới công nghệ và tài chính chỉ đơn giản là “làm việc của họ”, tạo ra những bước tiến lớn hơn cho đầu tư dân chủ hóa-ví dụ về điều này sẽ là các sản phẩm như quỹ giao dịch trao đổi (ETF), các nền tảng giao dịch như Robin Hood giúp đơn giản hóa người dùng trải nghiệm, các blog được hỗ trợ bởi truyền thông xã hội, các kênh YouTube và các nền tảng thông tin giải trí thay thế để xây dựng sự tự tin và sau đó rắc lên nguồn gốc này bằng một liều FOMO khổng lồ ở cấp độ văn hóa. Một cơ chế rõ ràng khác sẽ là thông qua thuế thu nhập cao hơn để chuyển hướng tiền sang đầu tư tài chính, và thuế thu nhập vốn lớn hơn để khuyến khích hành vi HODLing của thị trường chứng khoán. Đây chỉ là những ví dụ. Điểm mấu chốt ở đây là có một hộp công cụ vô hạn dành cho các mục tiêu xa hơn như vậy, cả có chủ đích cũng như tự nhiên theo cách khuyến khích tự nhiên của hệ thống.

“Nhưng hãy đợi đấy,” bạn nói. “Có gì sai khi tỷ lệ tiết kiệm cao hơn và tiêu dùng ít hơn? Rốt cuộc, đây không phải là nguyên tắc cốt lõi của nhiều Bitcoiners sao? ”

Vấn đề là ngay cả trước khi có sự thay đổi nghề nghiệp mang tính xã hội như chúng ta đang chứng kiến ngày nay, mức giá tài sản so với giá trị cơ bản của chúng đã vượt qua ngưỡng không thể quay trở lại, tạo ra cảm giác khó chịu về chủ nghĩa định mệnh cho nhiều người tham gia thị trường cởi mở.

Hàng chục năm tỷ lệ chiết khấu giảm dần đã đánh cắp quá nhiều giá trị trong tương lai đến nỗi không còn cây con nào mọc rễ trong tương lai. Vì vậy, vấn đề ở đây không phải là tiết kiệm trong và của chính nó, mà là những đồng cỏ tiết kiệm cụ thể mà các cá nhân đang được chăn thả. Tiết kiệm không phải là tiết kiệm nếu nó không được chuyển thành những kho giá trị thực sự. Chỉ cần đối diện, trong thực tế. Cách duy nhất để duy trì mức sống hiện tại đòi hỏi tốc độ tăng giá tài sản vĩnh viễn, do đó sẽ đòi hỏi ngày càng nhiều nợ hơn.

Nếu chính phủ và những người có ảnh hưởng văn hóa chuẩn mực muốn xuất khẩu một động lực như vậy cho đại chúng, chúng ta nên mong đợi kết quả là gì? Đó có phải là sự bình đẳng và phong phú không tưởng? Hay đó là kế hoạch hóa tập trung, một thị trường tự do bị gạt ra ngoài lề và hoạt động kinh tế xã hội hóa? Bạn đoán nó! Cửa số hai, Bob!

Nguồn: Business Insider, CBS

Khối Ba: Toán học

Một trong những biến số có ảnh hưởng nhất trong lịch sử gắn liền với sự kết thúc của thời kỳ ổn định và mạnh mẽ đã là bất bình đẳng giàu nghèo. Mặc dù độ lệch như vậy hiếm khi là nguồn gốc của sự sụp đổ hệ thống, nhưng nó hầu như luôn luôn là một triệu chứng của sự phân rã, và thường xuyên đóng vai trò xúc tác cho điểm tới hạn đi vào sự suy giảm. Từ người Maya đến Đế chế La Mã, Trung Quốc Tam Quốc đến người Ottoman đến các cuộc cách mạng Pháp, Nga và Trung Quốc, bất bình đẳng giàu nghèo luôn đóng một vai trò quan trọng.

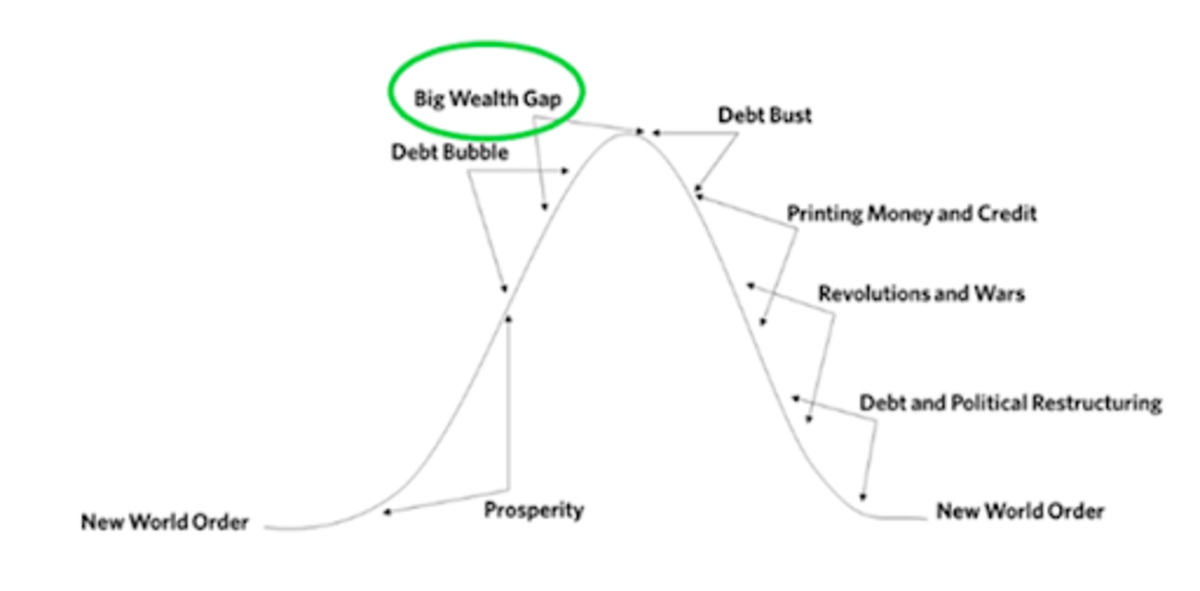

Nguồn: Ray Dalio,“ Trật tự thế giới đang thay đổi ”, Chương một

Đây là một vấn đề lớn đối với chiến lược của lớp nhà đầu tư đại chúng. This is because a goal of wealth redistribution with a strategy centered around asset inflation is statistically impossible to achieve.

Many proponents of this new investor class take the “fight fire with fire” approach. Yes, asset inflation — driven by modern monetary policy — has been the prevailing impulse of inequality over the last several decades. Why should the average individual not be able to get their just desserts as well? Ethically speaking, I take no issue with such retribution to some degree.

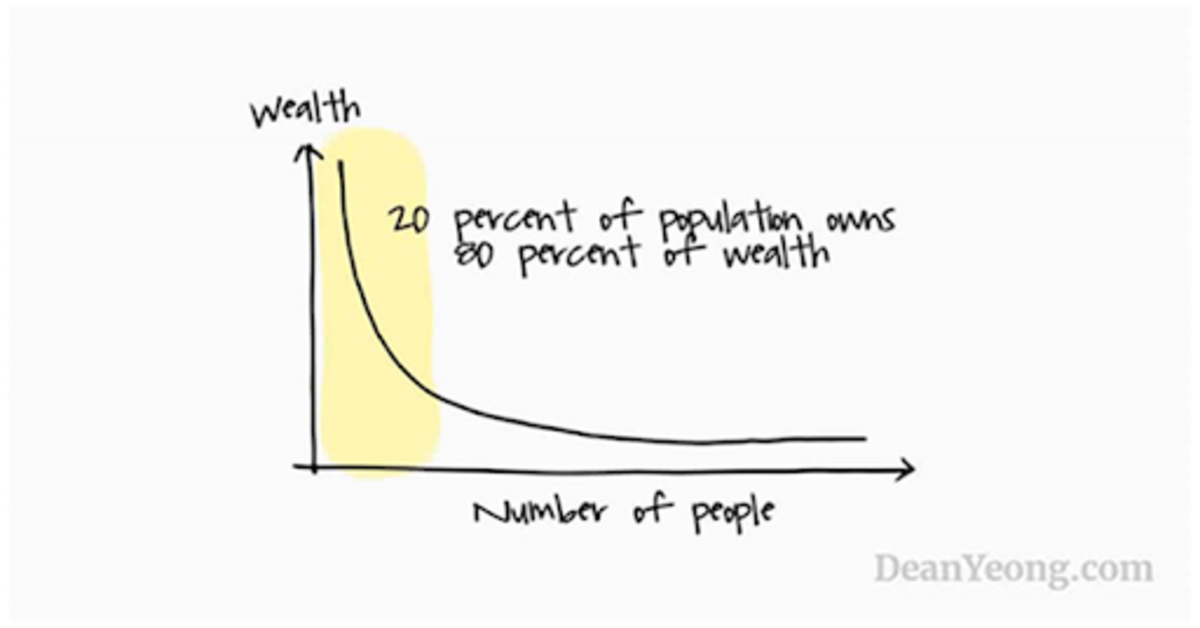

Unfortunately, it’s an illusion. The presiding growth curve that has been empirically witnessed as it pertains to wealth distribution has been found in the Pareto principle, a probability distribution whereby a small percentage of the sample group acquires most of the attainable value. Facets of this law, more colloquially known as the “80/20 rule,” are observed not just in wealth distribution, but prolifically throughout much of nature and human social environments.

We have experienced at least a half-century of Cantillon effects that have supported asset owners in exponentially outperforming relative to income owners. Even if we disposed entirely of such Cantillon effects and allowed the broader population equal access to financial assets going forward, and even if financial assets continued to generate historically anomalous returns, the “80 percenters” would never catch up. The reason for this is simply due to the nature of exponential growth curves as seen in the Pareto principle. Inequality would be maintained at the very least, if not continue its asymptotic expansion.

Pareto’s law: How asset inflation becomes a highly entropic state for wealth distribution, regardless of policy.

Source: DeanYeong.com

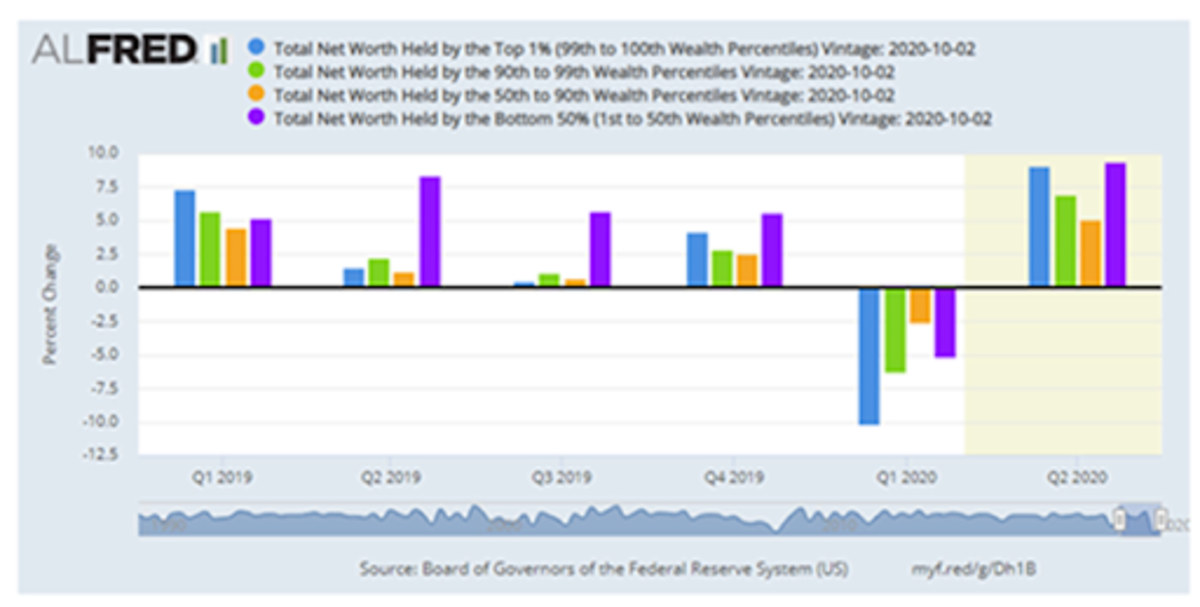

This Pareto probability distribution is exemplified quite dramatically after looking at 2020 as an outlier year, whereby the least wealthy percentiles actually saw the largest percentage improvement in wealth. However, while this is a lovely-sounding statistic for social media hype and political propaganda, it is purely a mathematical outlier caused by starting from such a low base and from such a low level of prior financial asset ownership.

Unfortunately, the banner year for the bottom 50% (purple bar below), did next to nothing to narrow the wealth gap from the top percentiles, as evidenced by the below chart.

Source: Federal Reserve

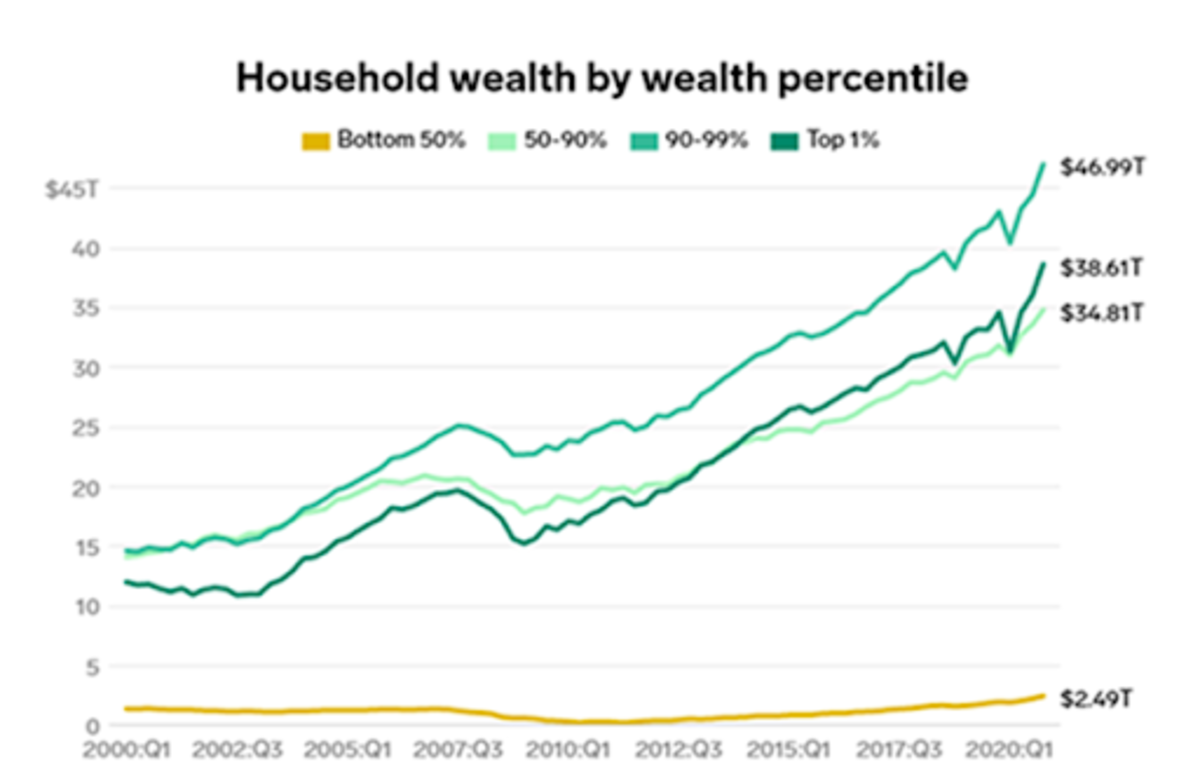

2020 did nothing to rectify the problems of inequality. In fact, inequality only got worse. Why would a continuation of asset inflation look any different in the future?

Source: Federal Reserve, “Distributional Financial Accounts”

If inequality cannot be corrected by the only policy tools available, the risks for social instability will only rise further. Ironically, when stability is threatened, this tends to only increase levels of centralization.

Have you ever been driving your car on a wet, slippery road, only to fish-tale unexpectedly? While our instinctual response would be to tense up and violently steer the wheel in the opposite direction to regain control, such a reaction would only worsen our dire predicament. One must steer into the chaos. Once control has gone, such a fate must be embraced, not opposed. This is the only way out. Further attempts at control only make matters worse.

Block Four: All Roads Lead To One Road, More Centralization

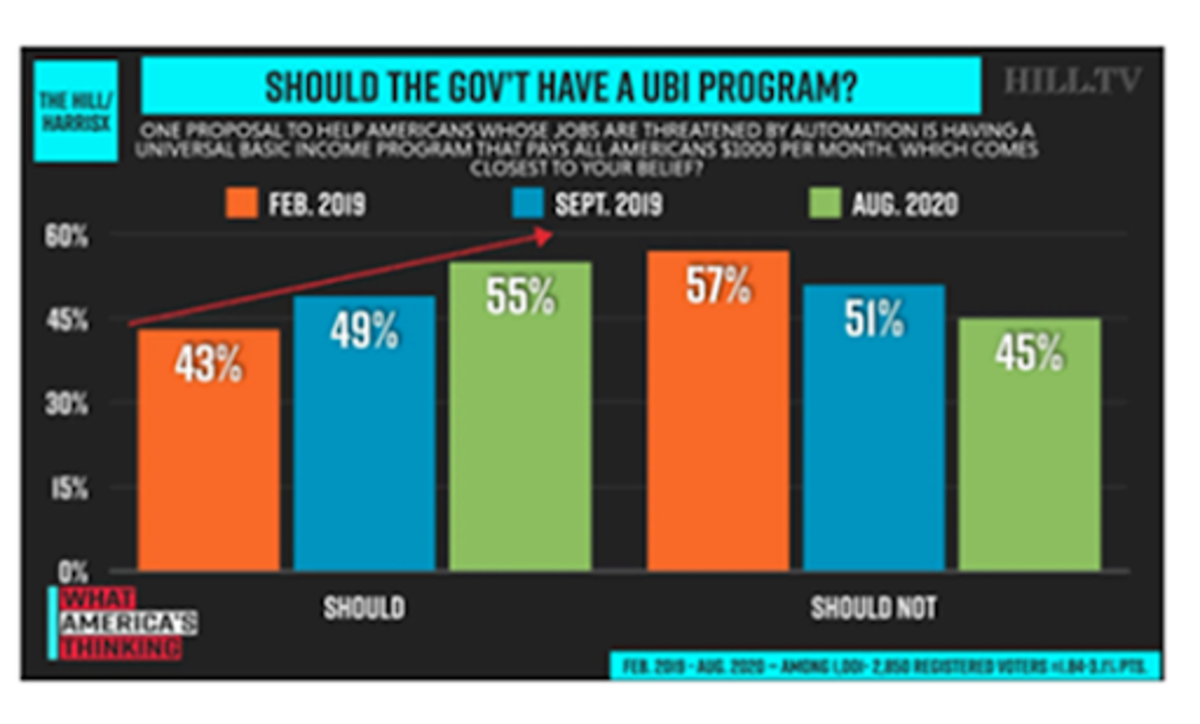

Once the inevitability of blocks one, two and three as stated above are appreciated, the path dependency of block four in our chain becomes absurdly apparent: Subsidizing asset prices through monetary debasement becomes the oblique way that society yields to ideologies like universal basic income (UBI).

UBI may end up in the very long run as explicit social welfare programs, or “helicopter money.” Of course, during COVID-19, we saw some discreet examples of this, turning something merely theoretical into a tangible part of the societal zeitgeist. However, it is a mistake to assume a linear path, that such policy will now settle as the initial and most effective vector for such policy going forward.

A more frictionless pathway would be the mechanism outlined above, whereby social welfare can be extolled circuitously. The brilliance of such a policy approach is that it would not require any incremental pieces of legislation, and no constitutional alterations to property rights. There are no foundational legal constraints. This implies that our current institutions have the power to accomplish such social welfare goals today.

One could argue that some changes would certainly make these aims easier to administer, like augmenting the Federal Reserve Act of 1913 and expanding the powers of the U.S. Treasury Department. However, the key point here is that such change is not required. If the reader finds this too far fetched, I would recommend listening to the taped conversations between ex-President Richard Nixon, and then-Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns. It has happened before in this country, and in less dire circumstances.

Source: TheHill.com

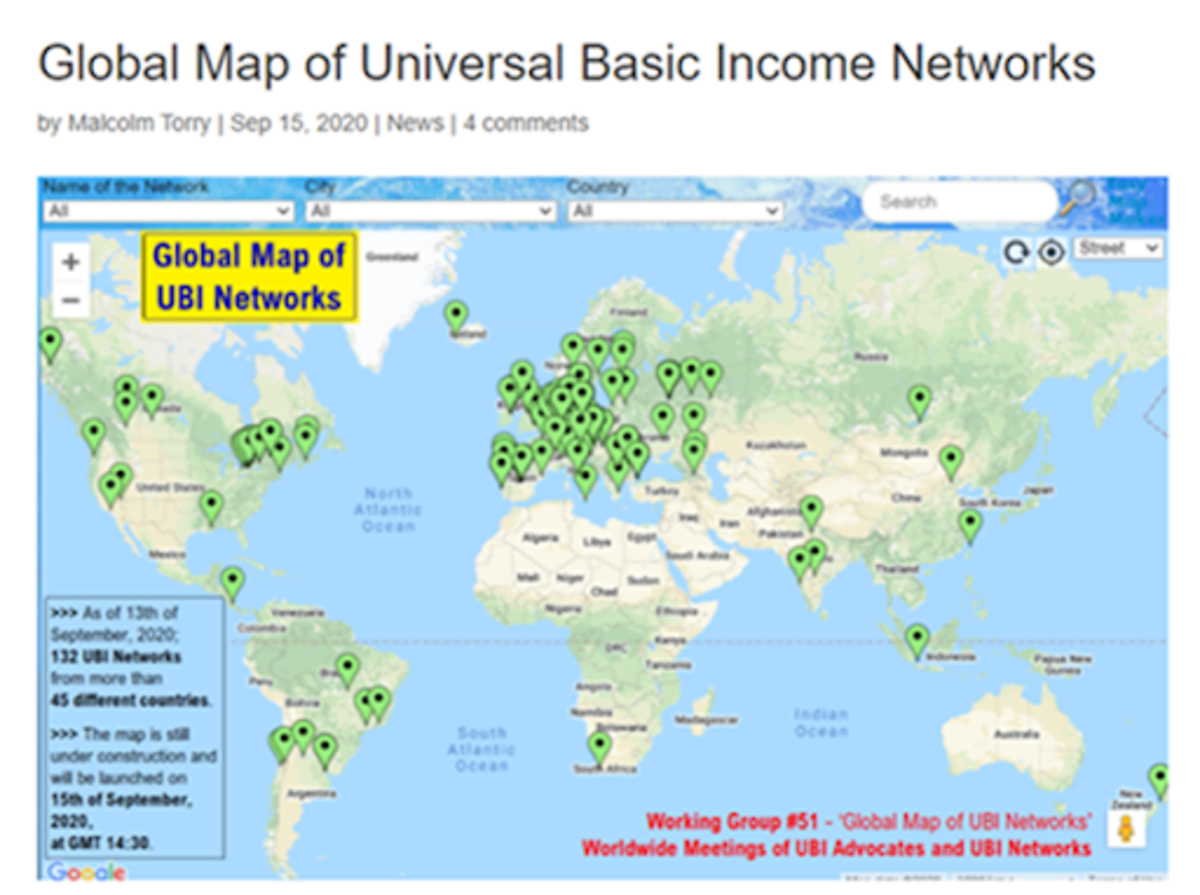

UBI advocates are here, and they have their own network effects:

“The map references not only networks with the sole purpose of advocating UBI, but also all organizations (networks, foundations, platforms, political parties, working groups within political parties, societies, study groups, etc.) that advocate for UBI.” Source.

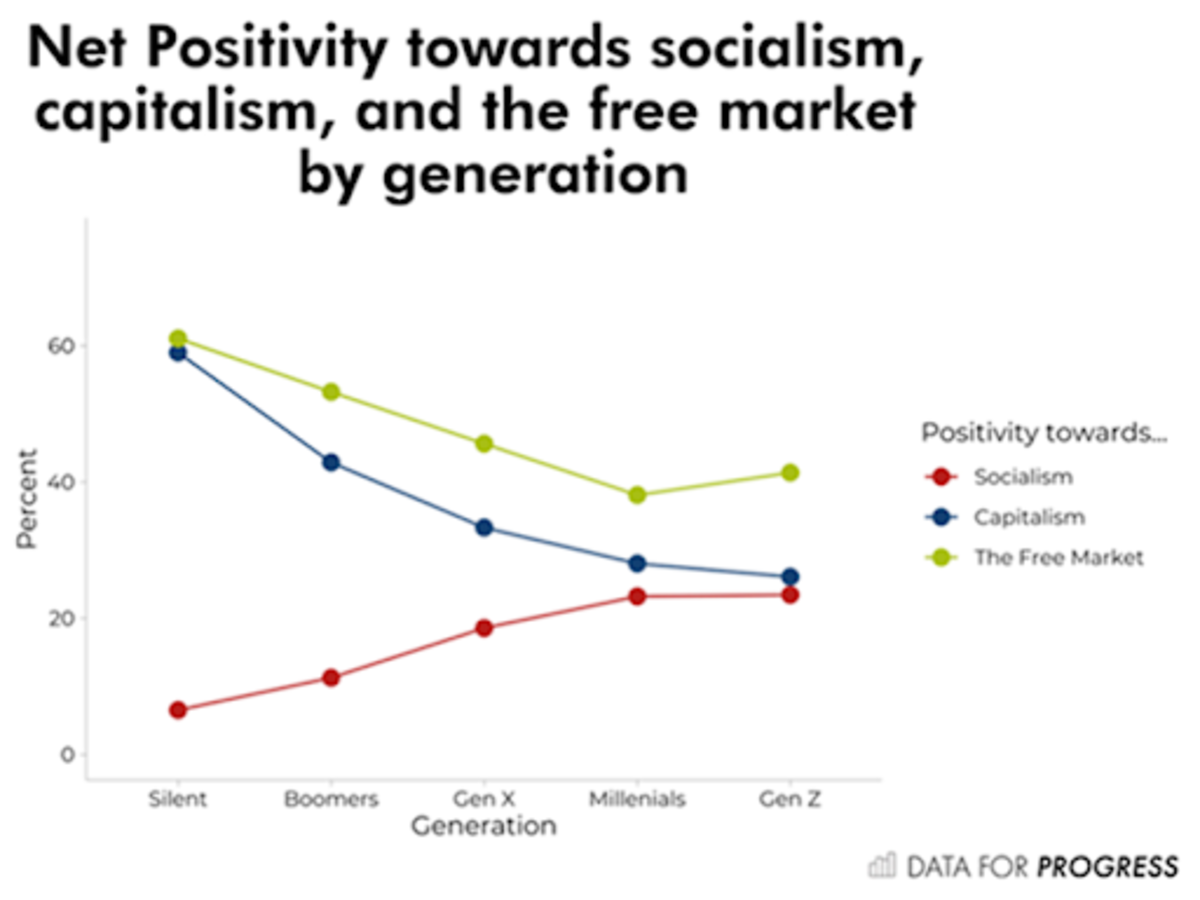

American openness toward socialism, and a commensurate disdain for capitalist ideals, has increased dramatically over the last four generations. This has been well documented with recent generations, particularly millennials, but it is important to recall that such a trend has been consistent well before that, even with the boomer generation relative to their parents and grandparents.

This is rather alarming when one considers that this generation has been the biggest beneficiary of financial asset prices (coincident with the full embrace of the fiat monetary system) of any generation in American history.

A Quick, “Passifict” Detour: Passive Investing Socializes Capitalism

Bitcoin may be humanity’s historically most perfect manifestation of a pacifist revolution, but passive investing is also a revolution, only with completely opposite implications.

Historical analogues are always dangerous, and each generational crossroads exhibit unique characteristics that can change the entire spectrum of outcomes. However, as a reference point, current trends reverberate with echoes of previous centralizing efforts designed to redirect our collective future and shift the public behavior, reminiscent of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “new deal,” as well as Nixon’s “great society,” or even going back to German Chancellor Bismarck and his social welfare policies in the 1880s, which greatly enhanced the Second Reich’s military capacity.

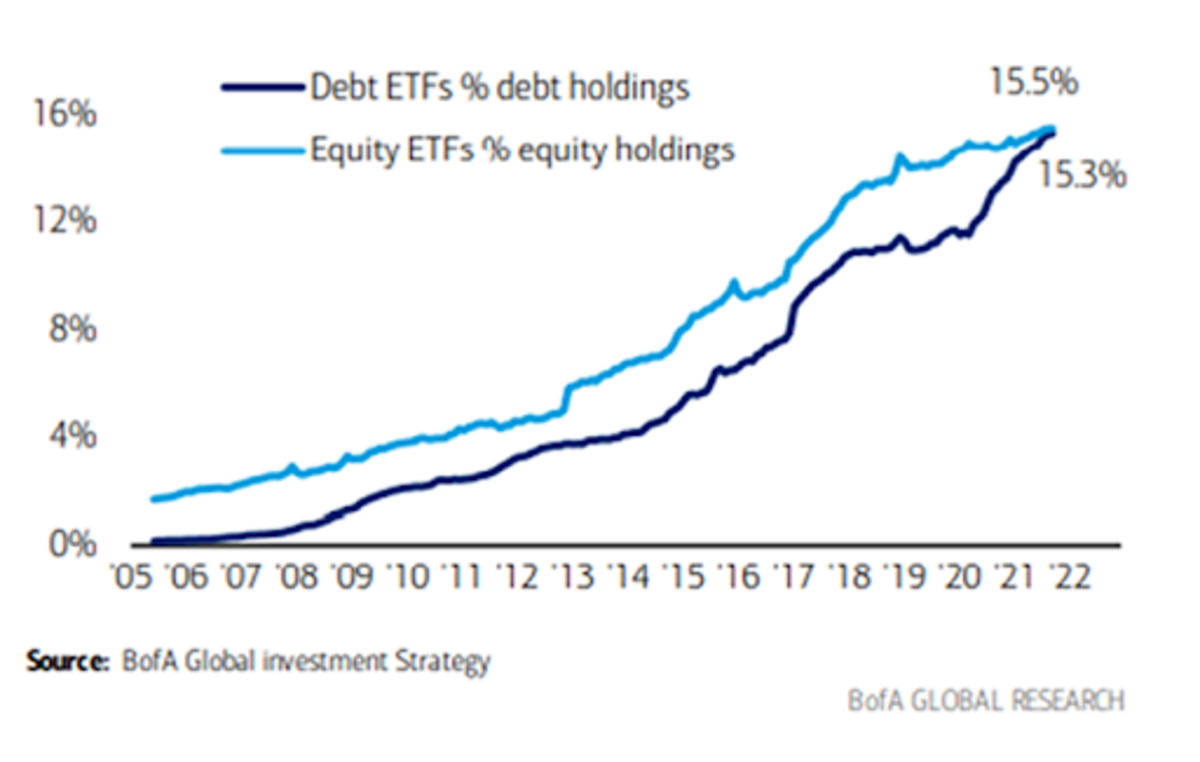

Passive or indexed investing vehicles such as exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are yet another example of this shift toward a “mass investor class.” While such a trend may seem innocuous, it is cultivating the seeds of enormous societal change.

As discussed by Inigo Fraser-Jenkins, a highly-regarded maverick quantitative equity strategist at Wall Street firm Bernstein, passive investing can be compared to Marxism. This may sound hyperbolic, but unfortunately, I believe he is on to something important here, the point being that the democratization of capital markets by way of ETF proliferation and other passive investing products inadvertently leads to a socialization of capital.

It would all but complete our societal transgression from liberal democracy to social democracy, a trend that has been gradually underway, but accelerating over the past 75 years. Fraser-Jenkins compared passive investing to other societal externalities like the tragedy of the commons, whereby behavior that may be optimal for the individual investor can be quite negative for the aggregate society when all actors behave the same way (we will return to the problem of the commons later).

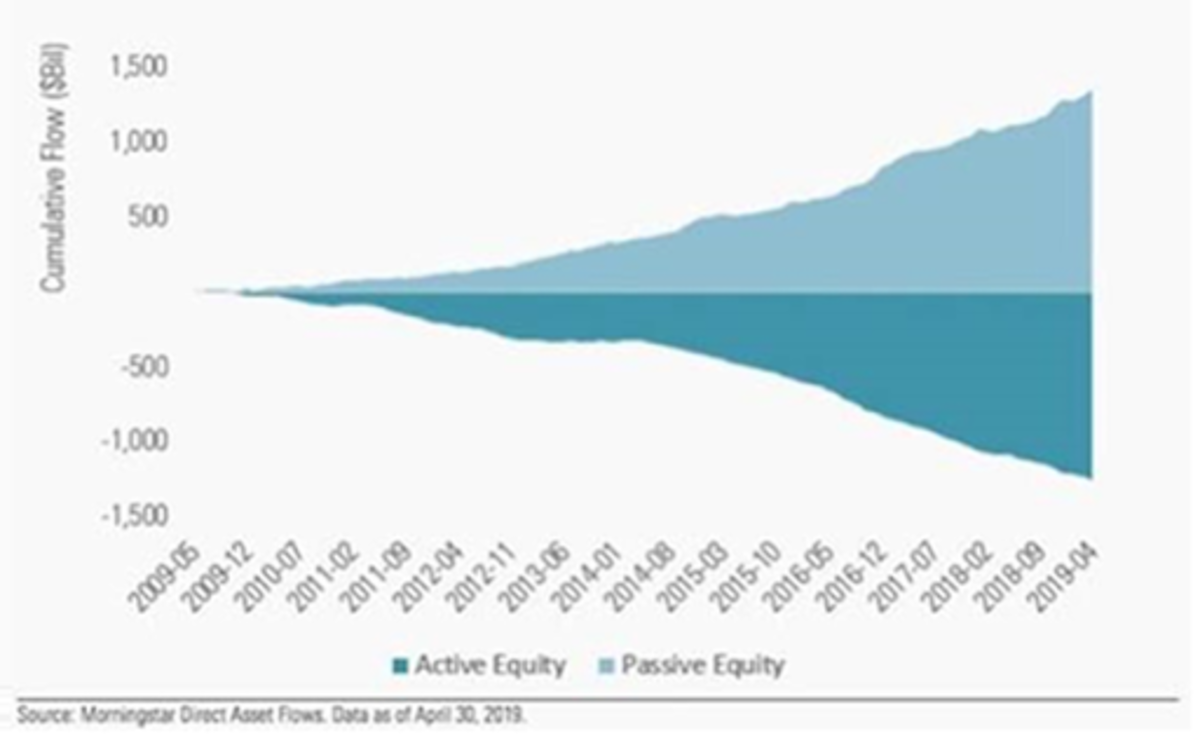

The unfettered expansion of passive investing does not look likely to subside any time soon. This is especially obvious when one simply looks at the below chart, or even at the hiring behavior on Capitol Hill, like the large representation of Blackrock alumni acquiring key roles in the current White House administration. Blackrock is the number-one manufacturer of passive investment vehicles in the world, with over $1.8 trillion in assets under management (followed by Vanguard in second place at $1.2 trillion).

Additionally, ESG and clean energy investment mandates further this shift, creating new products to bundle into thematic passive investment securities. Such bundles make it easier for ESG-approved companies to redirect capital away from those companies that do not fit the homogenous definitions prescribed. To be clear, there is nothing intrinsically bad about incentivizing cleaner energy and more sustainable economic practices. Of course, this is a good thing! However, when rules for such behavior become formalized, complex, and sometimes arbitrary and naively general, they impinge upon the competitive dynamics of free markets that would accomplish such goals more effectively.

Instead, such rules generalize the flow of investment, compensating those market participants best suited to game such a system. The new game defines the winners as those best able to adhere to the appropriate definitions as a means of acquiring low-cost capital. In a road paved with good intentions, we potentially end up in hell, robbing free markets of innovation, nuance, and differentiation. We write new rules of the game, rules that thoughtlessly increase centralization.

Mike Green, a distinguished researcher of passive investment stated back in 2020:

“Of managed assets, [passive investment] is now greater than 50% [and over 40% of total market capitalization]. That split though, is not uniform across demographics. Millennials are almost 95% passive. Boomers are only 20% passive. For the vast majority of millennials, their only exposure to the market… We make a lot of hype about things like Robin Hood and stuff, but the actual assets are tiny. The vast majority of the money that they’re getting is actually just going into things like Vanguard target-date funds.”

Active equity managers have seen outflows every year and passive investment vehicles have seen inflows every single year since 2006. And this trend is only accelerating:

Source: Morningstar

Source: The Wall Street Journal

Bank of America’s private client ETF holdings as percentage of assets under management (AUM). A hard trend to fight:

Source: Bank of America, Michael Hartnett

The passive singularity: Millennials have 95% of their retirement savings invested in passive vehicles. What is the logical conclusion of this freight train?

“One of the challenges that gets created as passive becomes a larger and larger share is that there becomes no discretion. There is no consideration of should the incremental dollar go in in the exact same fashion, right? That passive player has no instruction to sell. You exhibit increased inelasticity in terms of each incremental dollar that goes in. Imagine a scenario in which 100% of the owners of a company were passive and you tried to buy a share. There is no price at which they would be willing to sell to you unless they received an instruction from their end investors saying to sell shares to you. Prices could theoretically become infinite on that type of dynamic. Eventually, you would expect somebody to respond by saying, ‘All right, I will sell an additional share to you.’ Traditionally, that’s been accomplished by price-sensitive or return-sensitive discretionary managers who say, “Okay, this price is unwarranted by the fundamentals. Therefore, I’m willing to sell some of these shares to this person who’s expressing, in my view, an irrational demand for these shares.” If that demand is so strong and it gets absolutely extreme, people can synthetically create shares by shorting, but that is incredibly dangerous to do, an environment in which stocks are exhibiting this reduced elasticity.” –Green

The mass investor class faces a big incentive problem: What does the internet, digital property, and a tragedy of the commons have in common? Our retirement accounts.

The dismantled connection of choice from the capital allocation process brought about by passive investment proliferation has implications beyond the clear destruction of price signals. This is no small statement. A destruction of price signaling is as destructive as things can get for a capitalist system. Prices are the main form of communication we use in society to make appropriate economic decisions and choices. Its dissolution is of existential importance.

However, there are other problems to consider from this evolution of behavior as well. Ever since the runup to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, and at an accelerating pace since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, society has become more aware of the vast concentration of power that the internet giants and social media platforms carry.

Pockets of government and pockets of new and growing cultural progressive movements have quite easily influenced and incentivized these platforms to actively censor speech in our democracy. This is not a political statement, and this is not a judgement about the people being censored, but merely a factual observation about a key tenant of our democratic institutions. If the U.S. Constitution can be likened to the “core protocol algorithm” dictating the manner in which our collective network operates, this is a clear attack on one of the most vital rules of the protocol. How can we so readily dilute our core principals?

First, network effects are powerful. The ability of the internet companies to sustain and grow off individual resources, with extremely low detachment rates, cannot be underestimated.

How did this come to be? A failure in timing. As is often the case with disruptive technology, its usage preceded an appropriate infrastructure to handle it. Unfortunately, the Byzantine Generals Problem was not solved before the advent of the internet. Consequently, we have been suffering the consequences that a lack of enforceable property rights leads to in a digital world. A winner takes all society.

This is what the internet got wrong. You didn’t own anything. No one had any stake on the internet. Instead, value has been extracted by those who figured out ways to own the on-ramps and access points to the internet instead.

This group has become the “landlord class” of the internet, and the vast majority of value proffered by the internet and its myriad innovations of social communication has been funneled through this layer. The consequence, of course, has been more inequality, more surveillance and control, and more concentration of power. Further, we’ve witnessed a trend toward a reduction of quality of information. There is a diffusion of responsibility that engulfs the internet when ownership is so opaque and ephemeral. We are incentivized to create more noise than signal because when no one owns the land, there is no incentive to be a steward of that land to ensure its long-term sustainability, utility and productivity. Instead, the incentives align so as to be solely transactional. The more information one can manage, control and recapitulate, the more one can develop network effects and externalize the social and economic cost of a system that produces excessive noise and underproduces enough structured signals that could offer synergistic benefits across societal planes. That cost is shared by all of society. It’s a tragedy of the commons. All because the internet couldn’t address digital property rights.

The second issue here is that network effects also impact passive investing. Most passive vehicles are ETFs, that are indexed and weighted by market capitalization. The bigger you are, the more capital you attract. Size matters, aptitude and productivity do not. This takes us back to the Pareto principle and the 80/20 rule, setting the stage for increasingly non-linear distributions of capital. And in a world where access to low-cost capital is a massive competitive advantage, we end up with an obvious outcome. The big continually get bigger, and the small get only smaller. Or worse, the upstart disruptors may never have a chance, and we would never even know what could have been.

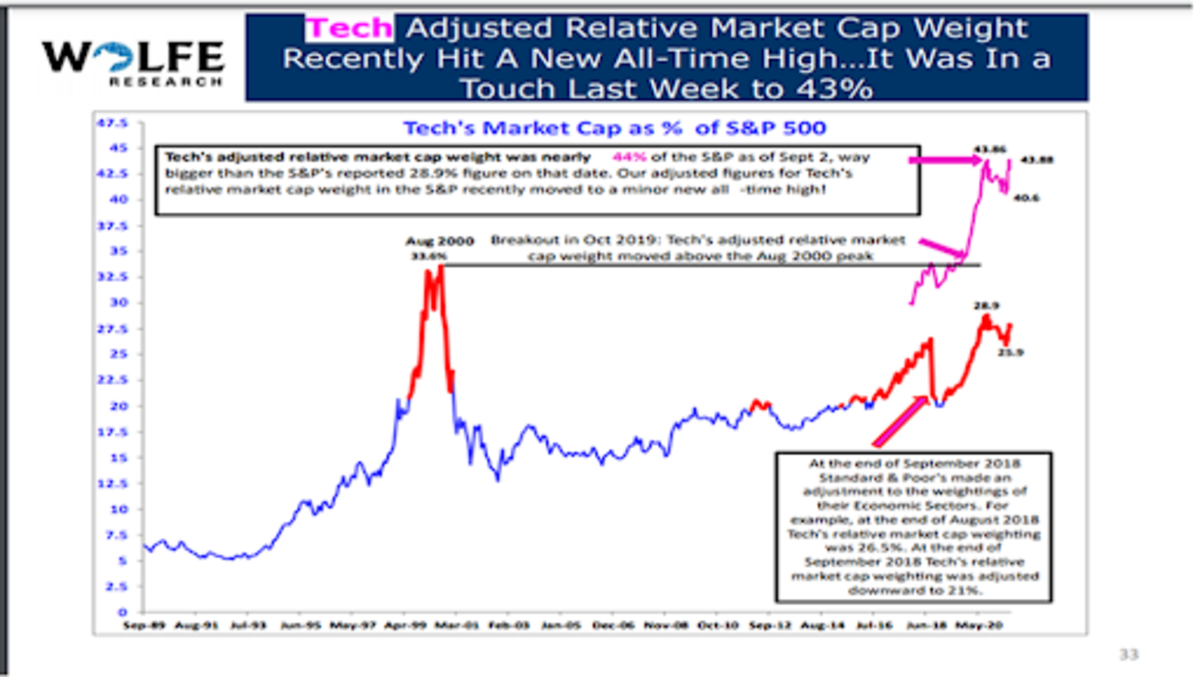

That brings us to the present, where just six behemoths have a near majority control of the entire equity market. Most investors do not blink at this statistic any longer. Professional investors have been numbed to such lopsidedness. However, imagine if such inequality persisted within the domain of political parties? In democratic institutions? In your childrens’ classrooms? But the real question we need to start seriously and honestly asking ourselves is this:

If the below chart only becomes even more extreme in its weighting distribution, and if our collective wealth is increasingly tied to the index it represents, what will our incentives be as the companies involved become even more centralized?

About 45% to 50% of our savings are tied to companies that could be actively censoring us, and indirectly eroding the very principles of the system that allowed them to prosper. This share of our savings will only grow further. Will we object? I certainly hope so. But so far, there is little evidence to support that aspiration. Unfortunately, passive investing, alongside a mass investor class, is likely to only help internet platforms and capital markets centralize further.

Major stock indices are mainly just six names now: Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft and Nvidia, totaling 42% of the equity market.

Source: Wolfe Research

Block Five: All Roads Lead To Zero

What happens when zero volatility is the new equilibrium?

After our modest digression into passive investing, let us now return to the last block in our chain. The final and most deadly flaw in the chain reaction socializing financial assets relates to volatility and the cost of capital. Mathematically speaking, publicly-administered financial markets that demand continuous appreciation, distributed broadly and without diversification, will require volatility to trend toward zero over time.

A simple law in financial markets, when assessing an asset’s volatility (as measured by its standard deviation of returns over a given period), is that the more vulnerable to uncertainty an asset is, the less it can absorb volatility. This is why, for example, equity investors are generally willing to pay lower valuation multiples for cyclical or economically-sensitive sectors relative to secular growth or defensive industries. These types of companies are more vulnerable to unforeseen events. When our financial markets are a tool of policy rather than an expression of free market capital allocation, we eventually become incapable of withstanding any uncertainty. And manipulation to affect policy outcomes would be the only way to ensure uncertainty’s suppression. If successfully orchestrated, volatility must eventually collapse toward a zero bound to accommodate this.

As our centralized debt trap expands in circumference, the risk-free rate must also trend toward zero, as has been the case over the past 40 years. Over time, the consequence of this could even be the elimination of the need for a private sector.

This last section is essential to our thesis, as it is the bridge that transports us from the current transitional sandwich era where we find ourselves juxtaposed between centralization and decentralization. This is the last stop on this transitional train as we push relentlessly down the path toward a more authoritarian world order. Given its level of importance in our story, it requires some more detailed explanation.

Centralization As A Black Hole: The Volatility Singularity

Source: Disney, Pixar

What is the volatility singularity? Previously, we have established the logical chain of cascading events that are required in our world’s existing model.

Debt must go up, so stocks must go up. Thus, rates must go down, so volatility must go down. When this happens debt will logically go up, leveraging the system even more, so stocks must go up to prevent collapse and inflate the debt bubble with a greater equity cushion… (stop for breath)… So, rates must go down again until zero, so volatility must go down until zero.

Volatility collides with zero. Everything goes to infinity. Yippie! The transcendent state where the difference between nothing and everything gets very fuzzy and rather philosophically confusing. Just as observed in the case of black holes, where physics starts to behave mysteriously and spooky as one approaches the event horizon, so too do economies. Things start to get pretty eerie as we approach the zero point event horizon in volatility.

Thinking about the problem in the following simplified manner may be helpful:

Anything divided by zero equals infinity. Financial assets returns are a function of volatility. A common formula used to calculate risk-adjusted returns is called the Sharpe ratio, which is an asset’s return during a given period, minus a market risk-free rate, divided by the investment’s standard deviation of returns. If volatility is, for all intents and purposes, equal to zero, so too is its standard deviation. Thus, we end up in a confounding situation in which excess returns are divided by nothing, and therefore magically become, well… everything.

Image source. Source of quote: Kurt Vonnegut, “Slaughterhouse-Five”

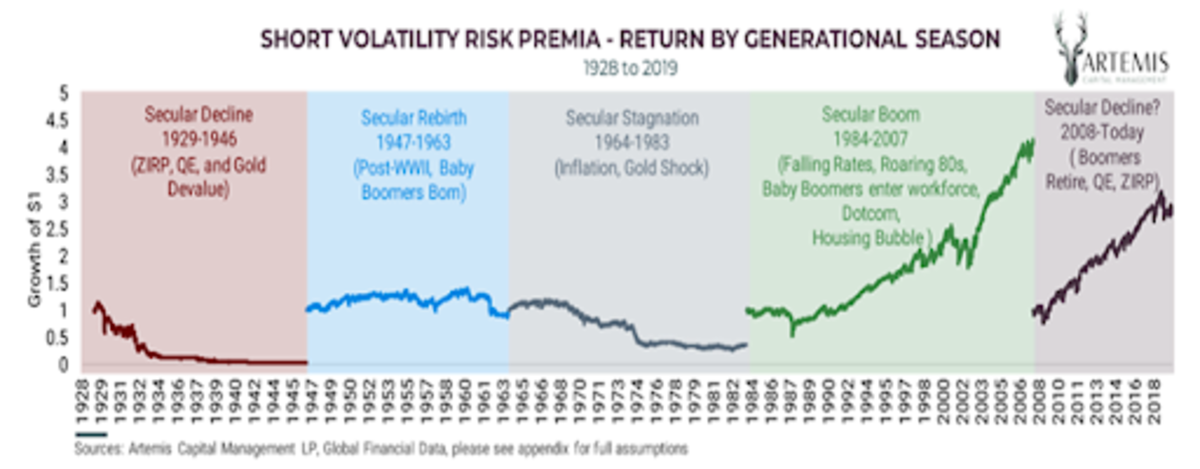

As macro volatility fund manager Christopher Cole excellently laid out in a 2020 piece titled “The Allegory Of the Hawk And The Serpent,” an investment strategy designed to short volatility, or benefit when it decreases, experienced temporally anomalous returns since the early 1980s, right when the financialization of Wall Street took off exponentially, and right as Alan Greenspan et al. began a campaign of moral hazard, at a time known as “The Greenspan Put.”

The stock market and nearly all financial assets in aggregate then become just a mere proxy for this “short volatility” expression.

Source: Artemis Capital, @vol_christopher

An Endangered Golden Goose

Cole, like many others, believes this period of declining volatility is mean reverting and must therefore repeal its nearly 40-year journey. While certainly possible over a cyclical short term time horizon given the magnitude of the move, a spike in volatility is unlikely to be palatable for any sustained period. The reason, as you might have guessed, is because of the deterministic nature of acceptable outcomes laid out above. The violence to the system that a spike in volatility would require would eviscerate so much wealth, so many debt obligations, that the policy response would be equally violent. Such a response is all but guaranteed because the crisis would be existential for those in power.

This outcome becomes more assured each day that goes by with greater reliance on financial assets to lift us into the future, each day that a citizen puts their first dollar of savings into such a system, and each day that another dollar is diverted away from new capital expenditure in favor of being recycled instead back into the existing sinkhole.

Below is a graph of the realized one-year volatility in the Dow Jones Industrial Index going all the way back to 1895. The pre-WWII average of this proxy for stock market volatility was about 20%, witnessing only one to two “black swan” spikes during a 50-year span. Meanwhile, the post-WWII average has been closer to 14.5%, with three black swan events observed only within a 30-year period!

This graph gives us two important pieces of information:

Volatility is trending lower over time. A move from 20% to 14.5% may not sound significant, but this is a nearly 30% decline in average volatility. The positive effect of such a shift has on underlying asset prices cannot be overstated. A system of declining volatility has come at the heavy cost of greater susceptibility to bouts of near-disastrous black swan events, external and internal shocks. And these events are not capable of being permitted to clear the imbalances that caused them, to self correct, as the system would break before such catharsis could be attained. Instead, each successive crisis forces policymakers to intervene at much lower levels of volatility than in the pre-WWII era. This of course fuels greater abdication of responsibility, which fuels the next crisis as we rinse and repeat, racing toward zero.

Source: @LudiMagistR, Bloomberg

Centralization Is A Fabergé Egg: Systems Which Require Stability And Efficiency Are Always Extremely Fragile

I recently came across a white paper authored by Ben Inker and Jeremy Grantham, famed hedge fund investors at GMO. They conducted a data mining project and looked at the prior periods of frothy financial markets like the 1999 to 2000 period, and similar historic periods of strong performance and excess returns. They were surprised to find that it wasn’t earnings growth, the level of real interest rates, or even GDP growth that mattered during such periods of excess and euphoria.

Instead, they found three consistent variables that were always part of the equation:

Atypically high profitability for one or some segments of the economy (this is finance speak for maximal efficiency rather than maximal productivity)The stability of GDP (as a proxy for overall economic activity)The stability of the rate of inflation

In short, markets care not about actual levels of growth, inflation and profits. Predictability is what matters. A financialized system and a mass investor class requires stability and loathes uncertainty. Said differently, our system of monetary inflation rewards monopoly formation, values efficiency over productivity, and requires reduced volatility to sustain itself.

Given that volatility is a natural phenomenon of any free system, suppressing it requires external and artificial forces. It requires a central authority to manage the system and to solve for low volatility. Our central bank policy of monetizing moral hazard is evidence of this. Moral hazard from this prism is simply a function that solves for low volatility, at all costs. And there are a lot of costs.

Moral hazard visualized: Credit Suisse Fear And Greed Index. Source: @LudiMagistR; Bloomberg; Credit Suisse

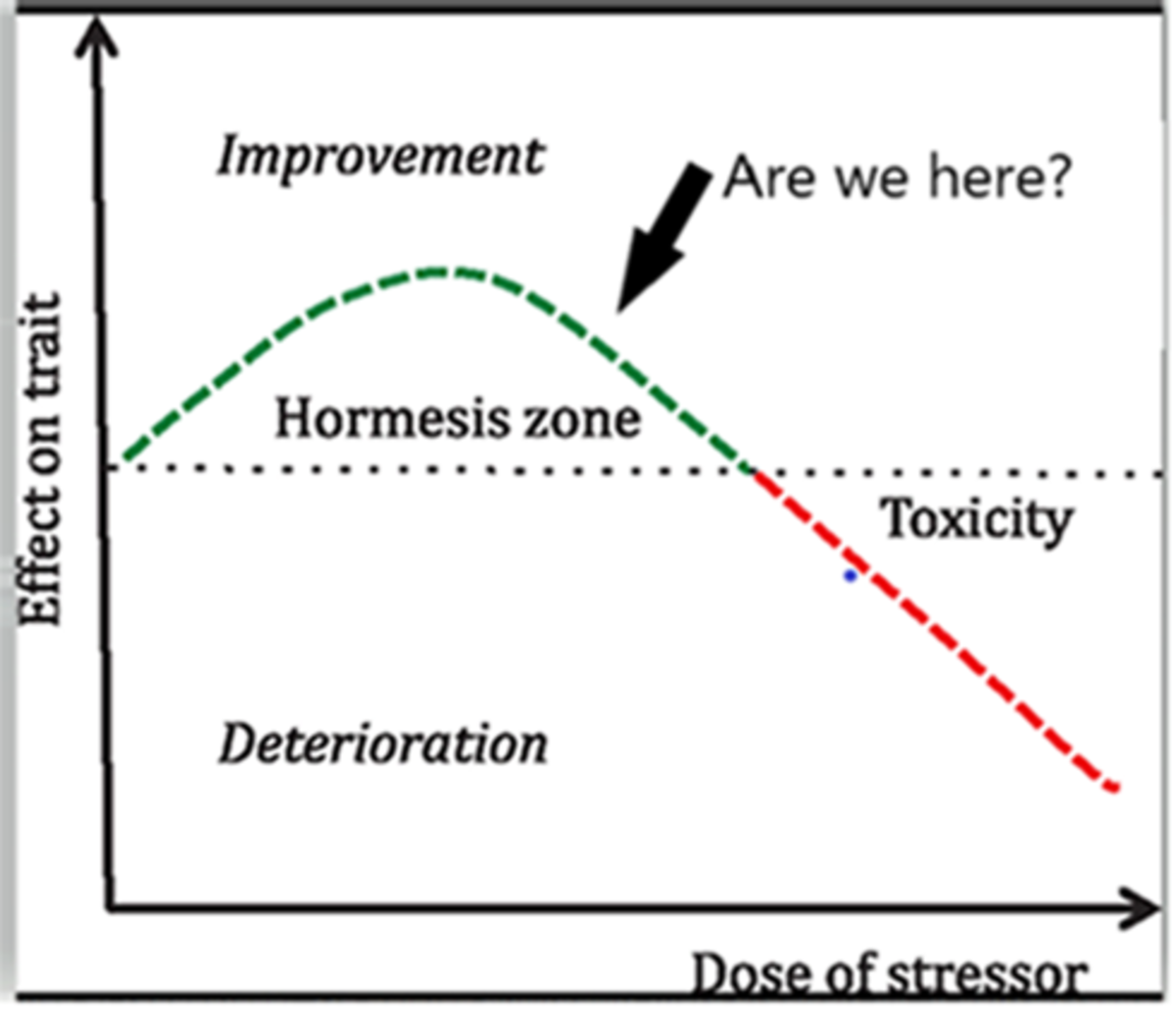

The Difference Between A Medicine And A Poison Often Comes Down To Dosage

While the importance of gains in efficiency are indeed a requisite aspect of technological progress as well as a tremendous generator of wealth for those providing such efficiency gains, there is always a trade off. A great example of this is the Bitcoin block size war of 2017, as well as the many utility protocols proliferating the crypto universe, optimizing for network throughput at the cost of much weaker decentralization. The irony is that the many use cases of blockchains become completely obsoleted without decentralization. Efficiency is great. It’s exciting. It often is associated with innovation. To a point.

Where is this point?

Any marginal gain in efficiency requires a marginal loss of resilience. Given that resilience is vague and incandescent, a decline can seem harmless until it suddenly breaks completely. This means that the relationship between efficiency and resilience is non-linear. There is always a point on the curve where the benefit of efficiency gains become precipitously overwhelmed by the cumulative trade-offs.

Source: Nassim Taleb, “Antifragile”; @LudiMagistR

Ok, fine. Let’s agree that the financial system is in fact becoming more fragile. What does this have to do with centralization of power? Shouldn’t a fragile system lead to the dissolution of power?

Short answer? No.

Less short answer? A centralizing power depends on vulnerability to validate its own existence. As the costs of centralization mount, is becomes existentially vital for an authority to lay claim on the sole ability to medicate the very ailments it fabricates, so as to traverse unstable times unscathed. Fragility maintains power. Power thrives on fragility.

Efficiency Is A Great Barometer Of Where We Are In The Macro Cycle

Why? Efficiency naturally peaks at the end of a regime. By the end of the regime, everyone assumes the cycle to be permanent because no one remembers a different world. We succumb to recency bias, forget history, and inadequately discount the inevitability of change.

Efficiency, fundamentally, is a way of optimizing processes or work to a specific environment. By the end of a regime’s lifespan, an environment’s self-selected economic participants have naturally maxed out adaptations to that one environment, having gone “all in” on its defining characteristics.

Thus, like a grain of sand placed on a growing sandpile, all that is needed is just one inopportune shift and the whole system cascades down with surprising fragility. A meteor hits, and we are cold-blooded, energy-consuming goliaths. Good luck with that!

We’ve of course seen this story time and time again throughout history, both at biological and evolutionary scales when diversity is overcome by uniform specialization, and throughout the annals of human history. This is one explanation as to why empires always eventually fall. Their successes eventually become their weaknesses. Efficiency helps fuel dominance in a world that values power as a function of resources, but it leads to dangerous deficits in resiliency that inevitably make them easy to destroy. This is also why empires are often built over long periods of gradual ascent, but often fall precipitously. Non-linearity.

Thus, somewhat counterintuitively perhaps, periods of maximal efficiency will precede periods of instability and upheaval.

An Obituary For The Private Sector

Now, let us return to volatility.

As the boulder of zero volatility and a fully-managed economy slides precipitously toward its Newtonian fate, there will slowly materialize some incredibly powerful implications for the structure of private property rights. This is because zero volatility and a required real risk-free interest rate held at zero or negative levels will logically push the aggregate cost of capital to extremes.

When there is no risk of material loss for capital, there becomes no discrimination as to how to invest it. The decision-making process becomes tied much more to government policy goals, cronyism and bribery, and other characteristics very similar to those of communist systems of governance. The corporation and the entrepreneur lose their utility in this world.

The birth of the modern corporation can be traced back at least to Adam Smith’s 1776 classic, “Wealth Of Nations,” interestingly published the same year that colonists here in America sought independence.

In this work, he lashed out at the “business association,” his era’s version of the state-owned companies, or the precursor of the “military-industrial” complex, or in China’s case the Sovereign-Owned Enterprise (SOE). These were institutions like the British and Dutch East India companies in Smith’s time.

He argued against monopolist business practices, which in turn paved the way for the legal autonomy of business outside the direct control of the government. As far back as 1844, corporations began earning the status of “personhood,” eventually granting them 14th Amendment rights in 1886. This paved the way for the evolution of corporate oversight toward the domain of the court system and not that of the executive and legislative branches.

The point here is that while we sometimes think of corporations as gatekeepers, monopolists, greedy beneficiaries of consumerism, debt and inflationary growth, these adjectives describe their failures within our current system, not their original purpose. The corporation was originally designed to bestow greater power to the entrepreneur and decentralize power away from the state.

By providing legal protections like limited liability, the corporate structure allowed for individuals to combine resources without unmanageable personal risk, which in turn allowed for the competitive acquisition of capital for investment. So, when the cost of capital and the risk of capital become immaterial, the existential purpose for the corporation becomes difficult to justify. And so the economy centralizes further with the erosion of one more source of decentralization.

What is so exciting about Bitcoin within this context is that it replaces the vacuum created from an impotent corporate private market structure with something much more decentralized and much better suited for the evolving digital information economy. It helps an increasingly interconnected economy divide labor beyond its current stalemate.

Bitcoin is a medium of specialization. Corporations were invented to be a specializing spoke of private capital, allowing for greater and more scalable division of labor. Unfortunately, in a world where the digital realm is becoming the majority sphere of economic activity, where individual property rights had not been assured prior to Bitcoin, the corporation instead has more often become a rent seeker, a bottleneck for competition, and a gatekeeper of digital property. This has had the perverse effect of decreasing our collective ability to specialize. Bitcoin solves this problem.

However, I am getting ahead of myself. We will get into this exciting potential in greater detail in part two of this series.

A Dangerous Cocktail: Why The Pareto Principle Matters

As the world becomes more interconnected, relationships become more “Paretian,” and less “normal,” or mean reverting. This is because the Pareto principle has shown empirically that complex systems often demonstrate extremely asymmetrical distributions of effect. Effects that only magnify as the system grows larger.

Prior to the interconnectedness driven by technologies and the scalability of digital networks, such Pareto effects were only discernible at ultra-large scales or where the complexity of the system was much larger than witnessed in everyday life, in fields such as macroeconomics, astronomy, geology, ecology and theoretical physics. But over time it is being appreciated just how pervasive this Pareto dynamic truly is.

In the business world, it has been shown that roughly 20% of customers often produce 80% of a company’s revenue. Eighty percent of a company’s output, likewise, is often generated by 20% of its employees. The pattern is found in many random systems. Eighty percent of highway accidents occur at 20% of the path traveled (near home), 80% of the cost of building is spent on 20% of the structure, and 20% of the world population is responsible for 80% of the pollution. The list could go on. But this simplified 80/20 rule actually understates the impact, as it is simply an approximate guide, the map rather than the road itself.

In fact, this 80/20 ratio can often turn into 99.9999/.0001 quite easily. Take a simple example where the square root of the total nodes in a given network is the number of nodes that are deemed to have the most measurable impact on that network. If we start with 10 nodes, we have about three nodes fulfilling that role, or about 30%. If the network grows to 500 nodes, we get about 22 nodes, or less than 5% of the network. If we end up with 500,000 nodes on the network, the figure would be about 707 nodes providing that impact, or a stunningly small fraction of 0.1%. Non-uniformity scales exquisitely.

As we begin to see, the Pareto principle is powerful in large systems, and is so important today as the world interconnects exponentially and in increasingly fractal patterns. The bigger the network, the more extreme the variance. Decentralization is a natural outcome of network building, especially if allowed to flourish without interference or external exploitation. Therefore, it is a logical conclusion as a general principle that decentralization increases variance and begins to break down previous patterns of mean reversion that are so characteristic of normal probability distributions.

Conversely, centralization craves more uniformity. Otherwise, there become too many outliers in the herd to corral, and the system becomes unmanageable. As networks proliferate, governments increasingly are driven existentially to ramp up the use of power and coercion against this natural force.

Not only is the world experiencing greater dispersion of outcomes, it is also changing at an increasingly faster pace. Raw data is pouring torrentially down upon us, overwhelming our neural capacity more each day. We are confused, overwhelmed and looking for anchors, answers, and authority.

“Black swan” or “tail risk” events, by definition, are not predictable by any model. Otherwise, they would not be black swans. Models often give us a false sense of stability, understanding, and confidence. The renowned behavioral economist Daniel Kanneman has shown that even when we are given statistical predictions that we know to be spurious, we embarrassingly cannot help but feel assured and make more risky decisions based on such irrelevant data.

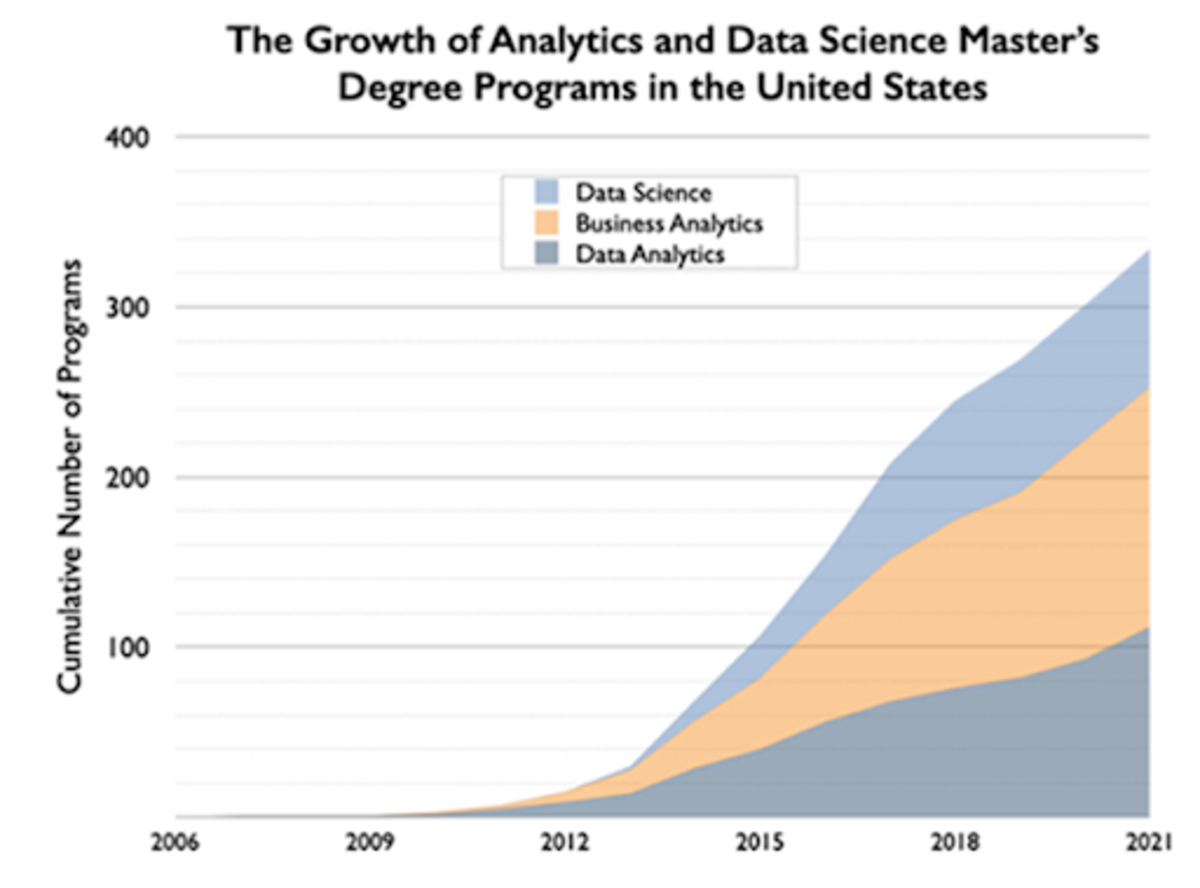

Nonetheless, the pace of change and data dumping has inspired us to overly romanticize and revere data accumulation, prediction, and data modeling techniques. We even have new professions that have popped up to deal with such issues, often aptly referred to as data “scientists.” Most major universities over the past decade have added degree programs for data science and it is now one the fastest-growing programs in academia.

Source: Michael Rappa, Institute for Advanced Analytics, May 2021

Now, let us more holistically recapitulate the situation described above. The cacophony of noise is getting ever louder, and meanwhile, our ability to filter this data to uncover the important signals hiding within has not improved at all.

We have developed technological tools that can filter the raw data and improve its informational extractability. However, these improvements are limited solely to endeavors that we are comfortable deferring to computers to manage for us. In all activities where humans still require involvement or apprehension, we are completely outmatched. On top of this, technology can be a tool, but it can also be a weapon. For every search, storage and AI tool that has helped to unbundle the noise into some semblance of a signal, there are other software tools that re-bundle the signal once again back into noise. Particularly social media, mainstream media, political propaganda and social science professions that overconfidently apply the newfound data abundance.

Taking all of these themes together, we have rampant technological shifts, overwhelming data propagation, and overconfident and confused human actors trying to adapt to these self-inflicted changes to achieve the unattainable: control. This means an increasing risk of the black swan events we so fiercely aim to circumvent. Less predictability, and more hubris as to our collective capacity to pattern-recognize and avoid those rare and historically pivotal events. This is a very dangerous cocktail.

An Homage To Endurance, Tenacity And Immutability

“I think much more likely is an even worse alternative: government will not cease inflating, but will, as it has been doing, try to suppress the open effects of this inflation. It will be driven by continual inflation into price controls, into increasing direction of the whole economic system. It is therefore now not merely a question of giving us better money, under which the market system will function infinitely better than it has ever done before… but of warding off the gradual decline into a totalitarian, planned system, which will, at least in this country, not come because anybody wants to introduce it, but will come step by step in an effort to suppress the effects of the inflation which is going on.” –Friedrich A. Hayek, “The Collective Works of F.A. Hayek,””Toward a Free Market Monetary System.”

Endurance, tenacity and immutability. While these attributes may sound too passive or unsubstantial to have value in our “move fast and break things” world, they are the exact traits required to survive the fragility of a system dashing feverishly towards instability.

Antifragility, an idea popularized in the 2012 book “Antifragile” by Nassim Taleb, describes systems or phenomena that gain strength from disorder. This book, part of a larger work focused on philosophical, statistical, and economic misconceptions relating to systemic risk, uncertainty, and randomness, has become part of the larger canon of Bitcoiner manifestos. This is despite Taleb’s recent baffling divorce from the community, which while a tad perplexing, should not detract from some of his work’s takeaways.

Bitcoiners have latched onto the themes of “Antifragile” as a framework to help elucidate some of Bitcoin’s game theory. How is it that there is no silver bullet that kills Bitcoin, there is no competitor that can magically overtake it, there is no government that can shut it down, and there is no central authority that can censor or confiscate it?

But the message does not stop there. Most important to the thesis of antifragility, each attack vector and shock to the system in fact causes Bitcoin to become stronger.

As Taleb writes:

“Some things benefit from shocks; they thrive and grow when exposed to volatility, randomness, disorder, and stressors and love adventure, risk, and uncertainty. Yet, in spite of the ubiquity of the phenomenon, there is no word for the exact opposite of fragile. Let us call it antifragile. Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better. This property is behind everything that has changed with time: evolution, culture, ideas, revolutions, political systems, technological innovation, cultural and economic success, corporate survival, good recipes (say, chicken soup or steak tartare with a drop of cognac), the rise of cities, cultures, legal systems, equatorial forests, bacterial resistance … even our own existence as a species on this planet. And antifragility determines the boundary between what is living and organic (or complex), say, the human body, and what is inert, say, a physical object like the stapler on your desk… The antifragile loves randomness and uncertainty, which also means — crucially — a love of errors, a certain class of errors.”

We have seen firsthand how the market can reward an asset that exhibits antifragility. Astute macro investor Louis Gavkal has wisely observed that this is how the U.S. treasury market has evolved.

Today, investors have institutionalized portfolio management, packaged into strategies like 60/40 asset allocations (bonds/stocks), and slightly more volatility-adjusted strategies such as risk parity. However, this love affair with the treasury market as a diversification tool has not always been the case, especially from the perspective of global investors. In fact, treasuries may be losing this status. The godfather of risk parity, Ray Dalio himself, just recently confirmed the view that he would rather own bitcoin than bonds.

What has historically given treasuries their stature of primacy for so many years was the dollar’s reserve currency role. A feat attained through war, geopolitical victories, petrodollar arrangements, and the trade-offs of increasing consumerism and domestic debt accumulation in the U.S. to supply dollars abroad. All punctuated by a parallel hyper-financialization of our economy, with regulatory incentives to own treasuries and a global system addicted to dollar-based leverage and short of adequate collateral.

This collateral shortage has become particularly acute after quantitative easing has been significantly reducing the public supply of treasuries since 2009. All of these factors have helped create a treasury market monster with very resilient network effects for the U.S. dollar. Resilient to deleveraging elsewhere, resilient to market volatility, resilient to dollar shortages, and even resilient to cyclical inflation.

The treasury market is a massive battleship that has been chugging along full steam in one direction for many years. However, this ship is now altering its course. And this process is ever so slowly chipping away at those network effects. As the U.S. dollar necessarily loses some strength as a reserve money, the system will either need to deleverage or find a new source of collateral, a new antifragile asset.

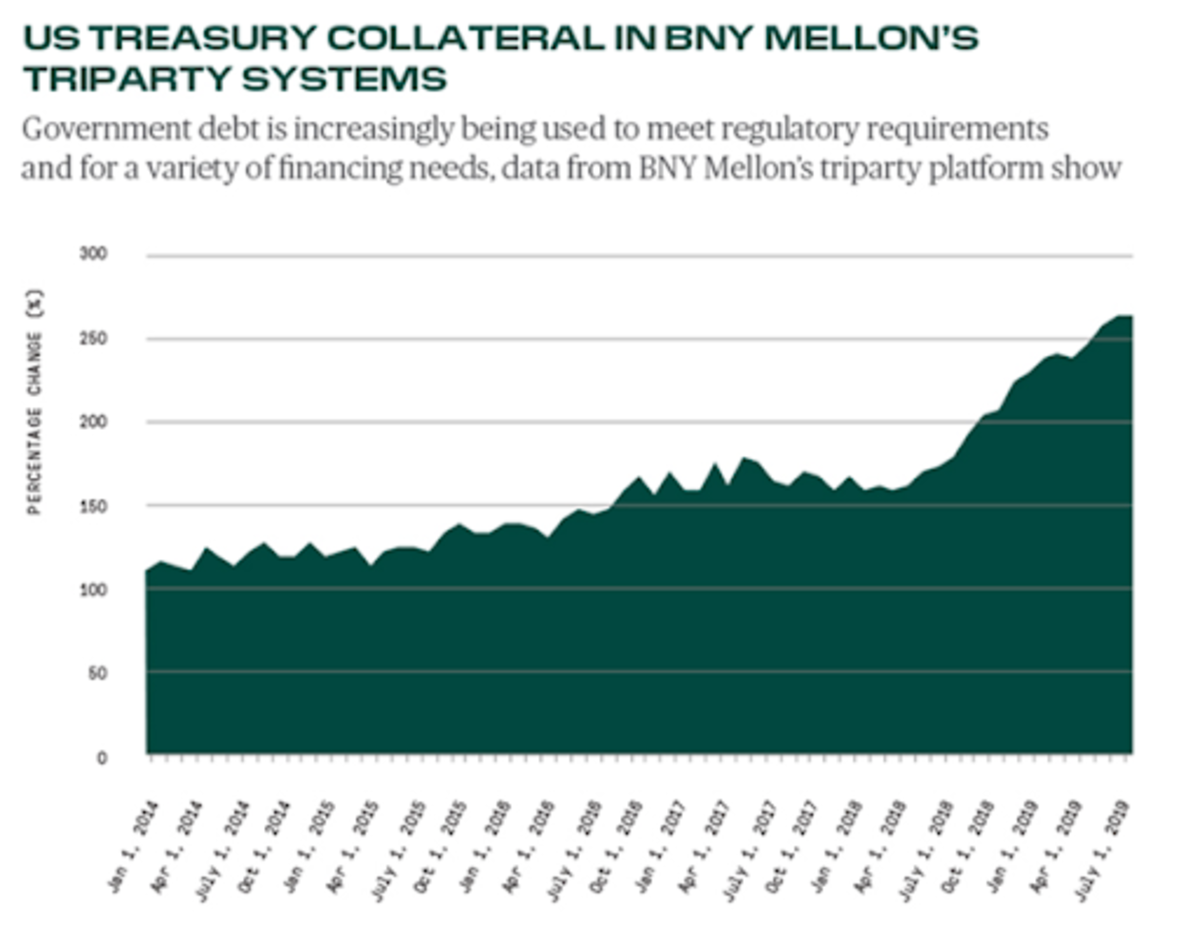

Source: BNY Mellon

One way to think of the U.S. treasury market’s ability to maintain buyers and holders despite real interest rates, at least at negative 1% (depending on your gauge of inflation), is that this market has become a weigh station, a storage space for dollar-denominated assets, intended to balance existing portfolios of dollar-denominated equity, real estate and corporate debt holdings, as a reserve account that incentivizes participants to remain within the bounds of the existing USD ecosystem.

The Eurodollar system, U.S. dollars banked or held outside of the U.S. banking system, evolved to help accomplish this goal more efficiently at the global level.

The Eurodollar market size has exploded as the U.S. economy began to financialize in earnest: First in the early 1980s and then again in the 1990s and post-dot-com burst.

The start of this in the early 1980s coincided with the start of a 40-year bull market in U.S. treasuries:

Source: Federal Reserve Board

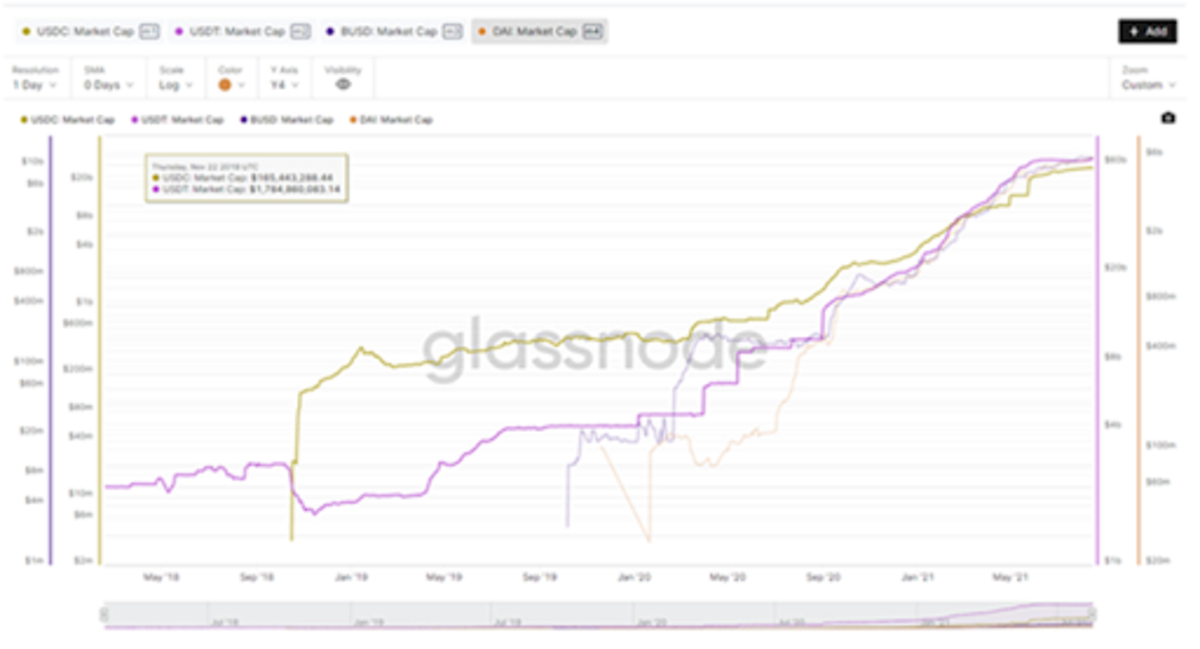

Such a concept of captively on-ramped capital is actually very similar to the stablecoin market in the Bitcoin and cryptocurrency ecosystems.

Source: @LudiMagistR; Glassnode

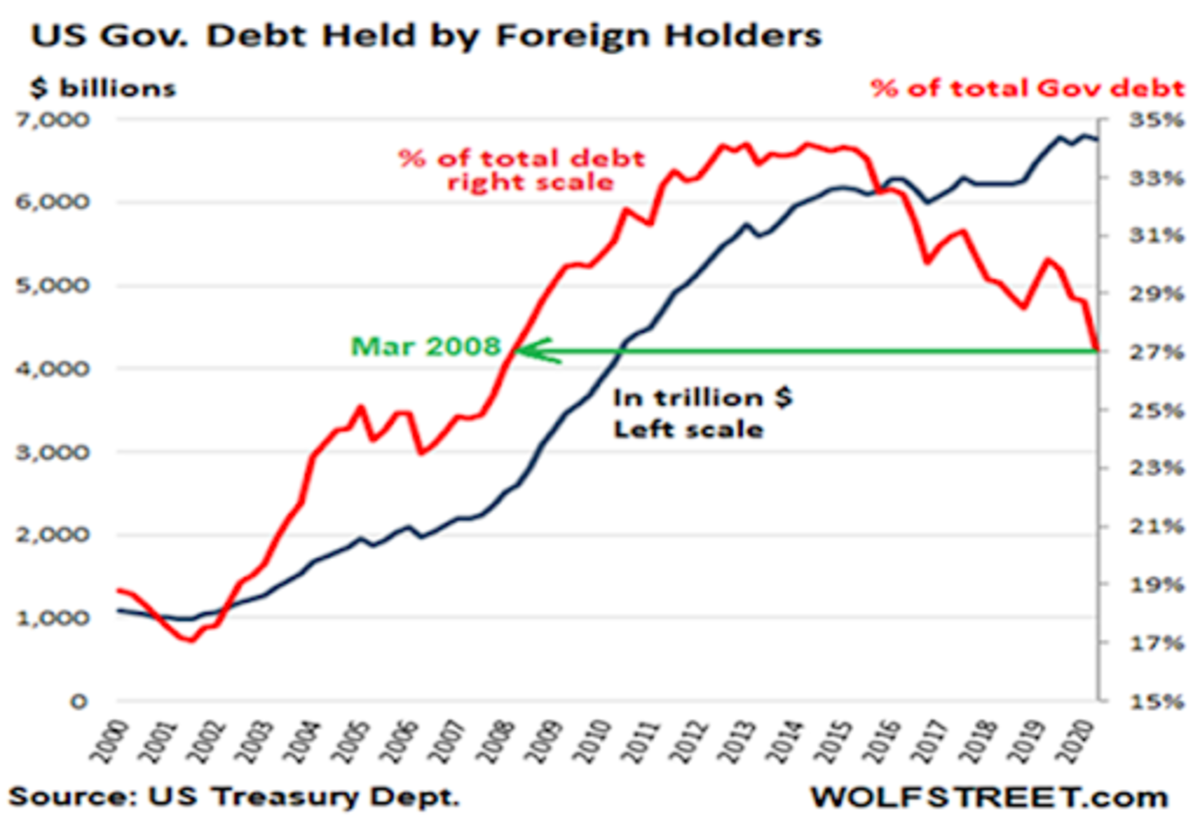

Unfortunately, for the U.S. dollar fiat ecosystem, there are signs of deterioration within its network effect. Foreign users are balking.

Source: Wolfstreet.com

A Poetic Phrase: Bitcoin Is A “Deep Structure”

“In a Paretian world, surface events can become a distraction, diverting attention from the deep structures molding these surface events. Surfaces are extraordinarily complex and rapidly evolving while the deep structures display more simplicity and stability. These deep structures are profoundly historical in nature — they evolve through positive feedback loops and path dependence. Snapshots become misleading and understanding requires a dynamic view of the landscape.” –John Hagel

We live in a world where things are intentionally made to fall apart. Quantity and popularity are valued above quality and depth. The news cycle is a meager 24 hours. Medical and health problems are addressed ex post facto with newly-invented medications and treatments, rather than by way of lifestyle changes and preventative measures.

Products are meant to become obsolete. Buildings are designed to last 20 years rather than 200. Tweets share ephemeral memes instead of lasting ideas, investments are made for instant return potential rather than lasting productive impact. And interest rates have collapsed to near zero, allowing us the mathematical permission to discount the future so that it is indistinguishable from the present.

We have lost our ability to think long term. We have no appreciation for durability over time. Therefore, we do not particularly value persistence because its main attribute is indeed durability over time.

Taking this a step further, if we do not place any material value on resilience, how could we value antifragility at the societal level? This is because antifragility is simply resilience in the form of a productive asset. By this I mean something that is durable, but also something that improves over time. It is no wonder then, that even Bitcoiners may be undervaluing antifragility.

This irony is further extended by the fact that just at the time when civilization least values such a high-powered form of durability and productivity happens to also be when these attributes are most desperately needed.

“An Ocean’s Ode To Volatility”

Oh waves, Crash thunderously

Unshackle my bounty of lost minerals

So they may rise and greet my surface foam

Antifragility is an embrace of volatility.

Volatility is the mathematical expression of what biologists and evolutionary scientists might call a “stressor.” Biological organisms crave stasis. Volatility, on the other hand, is a natural characteristic of all complex systems. This is because the greater the number of variables, the greater the number of possible outcomes. Stressors lead to adaptation and growth, which leads to survival, which builds resilience, which lays the foundation for more resilience and growth.

It is a positive compound growth formula because the more resilient we get, the more volatility we can swallow, without choking on it. As implied above, an increase in volatility can be thought of in this context as just a greater range of circumstances. But this can come from two sides, like a matrix of potential outcomes.